The cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccines: Global Evidence

When implementing vaccination strategies, health economic evaluation is an important indicator to consider alongside vaccine safety and efficacy. The economic evaluation of HPV vaccines is critical to improving the design of vaccination programs and optimizing resource allocation. The slow development of cervical cancer and other HPV-related diseases means the protective effect of the HPV vaccine can last for years. Researchers usually use mathematical models to estimate the long-term cost-effectiveness of vaccine interventions. One of the most commonly used health economics evaluation metrics is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), calculated as the ratio of incremental cost to incremental effect. The WHO recommends that an intervention strategy is not cost-effective if the ICER exceeds three times GDP per capita.

Table 1: HPV vaccine cost-effectiveness in selected high-income countries

| Country | Year | Phase | Type of vaccine/ type of prevention | Fraction of coverage % | Age of inoculation | Price (USD) / dose | Vaccination dose | ICER/ QALY | GDP | ICER/ GDP | Cost-effectiveness level |

| United States | 2015 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 100 | 12 | 34.992 | 55.837 | 0.63 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2014 | dynamic | 16/18 | 100 | 12 | 37250 | 0.67 | Very cost-effective | ||||

| 2015 | dynamic | 16/18 | 100 | 12 | 73.483 | 1.32 | Cost-effective | ||||

| 2011 | static | 16/18 | 100 | 12 | 134 | 3 | 59.041 | 1.06 | Cost-effective | ||

| 2015 | static | 16/18 | 100 | 35-45 | 166102 | 2.97 | Cost-effective | ||||

| 2004 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 70 | 12 | 100 | 3 | 4.305 | 0.08 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2004 | dynamic | 16/18 | 70 | 12 | 100 | 3 | 13.087 | 0.23 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2003 | mixing | 6/11/16/18 | 70 | 12 | 300 | 3 | 14.226 | 0.25 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2003 | mixing | 16/18 | 70 | 12 | 300 | 3 | 20347 | 0.36 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2016 | mixing | 16/18 | 33 | 12-17 | 32.526 | 0.58 | Very cost-effective | ||||

| Canada | 2008 | static | 6/11/16/18 | 100 | 12 | 120 | 3 | 23.351 | 44.310 | 0.53 | Very cost-effective |

| 2008 | static | 16/18 | 100 | 12 | 120 | 3 | 35.358 | 0.80 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2009 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 80 | 10 | 120 | 3 | 13.830 | 0.31 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2007 | mixing | 16/18 | 80 | 10 | 120 | 3 | 17.990 | 0.41 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2008 | dynamic | 16718 | 75 | 12 | 120 | 3 | 37.677 | 0.85 | Very cost-effective | ||

| Britain | 2013 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 85 | 13 | 95 | 3 | 45760 | 41324 | 1.11 | Cost-effective |

| 2004 | static | 6/11/16/18 | 80 | 12 | 100 | 3+1 | 47.602 | 1.15 | Cost-effective | ||

| 2014 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 80 | 12 | 95 | 12.483 | 0.30 | Very cost-effective | |||

| 2014 | dynamic | 16/18 | 80 | 12 | 95 | 21504 | 0.52 | Very cost-effective | |||

| Australia | 2009 | static | 16/18 | 80 | 12 | 115 | 3 | 16710 | 45514 | 0.37 | Cost-effective |

| Denmark | 2014 | dynamic | 1618 | 85 | 12 | 20 | 3 | 14237 | 46.635 | 0.31 | Very cost-effective |

| 2014 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 85 | 12 | 20 | 3 | 5.748 | 0.12 | Very cost-effective | ||

| Germany | 2009 | dynamic | 16/18 | 50 | 12-17 | 110 | 3 | 15.434 | 47268 | 0.33 | Very cost-effective |

| 2009 | dynamic | 6/11/16/18 | 50 | 12-17 | 110 | 3 | 7.835 | 0.17 | Very cost-effective | ||

| Nether-land | 2012 | mixing | 16/18 | 100 | 12-17 | 150.4 | 3 | 26865 | 48459 | 0,55 | Very cost-effective |

| 2008 | mixing | 16/18 | 85 | 12 | 100 | 3 | 29.602 | 0.61 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2008 | static | 16/18 | 50 | 12 | 88.1 | 3 | 26199 | 0.54 | Very cost-effective | ||

| 2008 | static | 6/11/16/18 | 50 | 12 | 88.1* | 3 | 21459 | 0.44 | Very cost-effective |

Table 2: Cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccines in selected low- and middle-income countries and regions

| Year | Country/region | Research perspective | Age of vaccination (years) | Cover rate (%) | CPD (dollar) | CYP ( dollar) | ICFR (USD / QALY) | ICER (Screen) (USD / QALY) | Core conclusion |

| 2011 | Thailand | SOC | 12 | 80 | 2.3 | 11.5 | Cost savings | – | ABCd |

| 2012 | Thailand | HCP | 11 | 100 | – | 343.0 | 8.890 | – | Abcd |

| 2011 | Thailand | SOC/ HCP | <12 | 100 | 430 | 1354.0 | 12642 | 16000 | ABCd |

| 2010 | Malaysia | SOC | 13 | 96 | 158.0 | 499.5 | 18603 | – | ABCd |

| 2010 | Malaysia | SOC | 15 | 96 | 52.4 | 183.7 | 4158 | – | ABCd |

| 2008 | Vietnam | SOC | 9 | 70 | 2.6 | 13.1 | – | 1554 | ABCd |

| 2008 | India | SOC | <12 | 70 | 2.3 | 11.5 | Cost savings | – | ABCd |

| 2007 | Brazil | SOC | 9-12 | 70 | 6.5 | 32.7 | Cost savings | – | ABCd |

| 2012 | Brazil | HCP | 12 | 80 | 30.8 | 30.8 | – | – | ABCd |

| 2012 | Brazil | HCP | 12 | 85 | 15.2 | – | – | – | Abcd |

| 2007 | Brazil | SOC | 12 | 90 | 6.5 | 33.0 | Cost savings | – | AbcD |

| 2012 | Brazil | HCP | 12 | 90 | 5.0-120.0 | 25.0-556.0 | – | – | abod |

| 2008 | Chile | HCP | 12 | 100 | 70.0 | 355.0 | – | 33309 | aBcd |

| Poland | 373.0 | 597.0 | – | 35602 | |||||

| 2012 | Peru | SOC | <12 | 82 | 70 | 34.9 | 11717 | – | aBcd |

| 2010 | Lithuania | HCP | 12 | – | – | – | 6172 | – | Abcd |

| 2008 | Mexico | HCP | 10 | 82 | 131.7 | – | 11927 | 11631 | ABCd |

| 2007 | Mexico | HCP | 12 | 80 | – | – | – | 4.502 | aBcD |

| 2012 | East Africa | SOC | <12 | 70 | 0.6 | 5.8 | 2.926 | – | ABCd |

| 2009 | South Africa | SOC/HCP | <12 | 80 | 120.0 | 804.0 | – | 1521 | aBcd |

| 2011 | GAVI | SOC | 12 | 70 | 2.0 | 11.5 | 230 | – | Abcd |

| 2008 | GAVI | SOC | 12 | 70 | 2.0 | 11.5 | 622 | – | Abcd |

| 2008 | Latin America and the Caribbean region | SOC | 9-12 | 70 | 5.0 | 28.8 | – | 392 | aBcd |

| 2008 | Asian-Pacific region | SOC | <12 | 70 | 2.0 | 11.5 | – | 622 | ABCd |

| 2009 | The whole world | HCP | 12 | 100 | – | 4.7-10.9 | 131-408 | – | ABCd |

(Table 1&2 source: H.Q. Wang, F.F. Zhao, & Y. Zhao. (2019). Expert consensus on immunoprophylaxis for cervical cancer and other human papillomavirus-associated diseases. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53 (8), 761-803. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.08.001)

Tables 1 and 2 show the cost-effectiveness results of HPV vaccines in some high-income and low- and middle-income countries. Most of the studies found HPV vaccines cost-effective or very cost-effective, but due to differences in vaccine types, costs, target populations, model assumptions, parameters, and calculations, there are some differences in the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios observed in the studies. For future policy decision-making, it is necessary to consider the actual situation, particularly each country’s economic development level, vaccine types, and target population, to conduct specific analyses.

Incremental cost-effectiveness studies of HPV vaccination in high-income countries have shown that the bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines are cost-effective for eligible women, even under different vaccination coverage conditions, whether in dynamic, static, or mixed studies. Although economic evaluation studies conducted in developing countries are limited compared with those in developed countries, growing evidence shows HPV vaccination is also cost-effective for eligible women in developing countries [1].

Health economics studies of HPV vaccination in China

Several studies have been conducted in China to develop dynamic and static models to measure the cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination [2, 3]. Table 3 summarizes some of the economic evaluations of HPV vaccination conducted in China.

Table 3: Selected health economics studies of HPV vaccination in China

| Author, year | Type of vaccine | vaccine price | site coverage | Vax age | Key findings |

| Mark, 2014 [4] | Three doses of bivalent vaccine | PAHO price is about $39 with an administered cost of $15 | 100% | 12 years old | At a cost of approximately $3,210 per disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) reduction, vaccination is extremely cost-effective |

| Liu, 2016 [5] | Three doses of bivalent vaccine | Three doses cost 1900 CNY with an administered fee of 54 CNY | 70% | 12-55 years | Combined with cervical cancer screening, HPV vaccination is cost-effective before 23 years old for rural women and before 25 years old for urban women by age 25. |

| Zhang, 2016 [6] | Three doses of bivalent vaccine | 247 CNY per dose | 70% | 12 years old | Very cost-effective when vaccine prices are 87-630 RMB (rural) and 87-750 RMB (urban) |

| Mo, 2017 [7] | Three vaccination schedules with 2/4/9-valent vaccines | Estimated at 2,000-3,000 CNY for three doses based on Hong Kong prices; Nine-valent vaccine price being 1.1 times of the 4-valent vaccine; Vaccination costs around US $4.84 | 20% | 12 years old | Only when screening coverage increased to 60% ~ 70% did the HPV2 and screening combination strategy become economically feasible. The combination of the HPV4/9 vaccine with current screening strategies for adolescent girls was highly cost-effective |

| Zou, 2020 [8] | Two doses of bivalent domestic vaccine | $99.80 | 70% | 9-14 years | Using a willingness-to-pay threshold of 3 times China’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, vaccination combined with screening with rapid HPV testing every 5 years would be the most cost-effective intervention. When the total cost of vaccination is reduced to $50, the combination of vaccination and screening will be more cost-effective than screening alone, even at a willingness-to-pay threshold of 1x GDP per capita. |

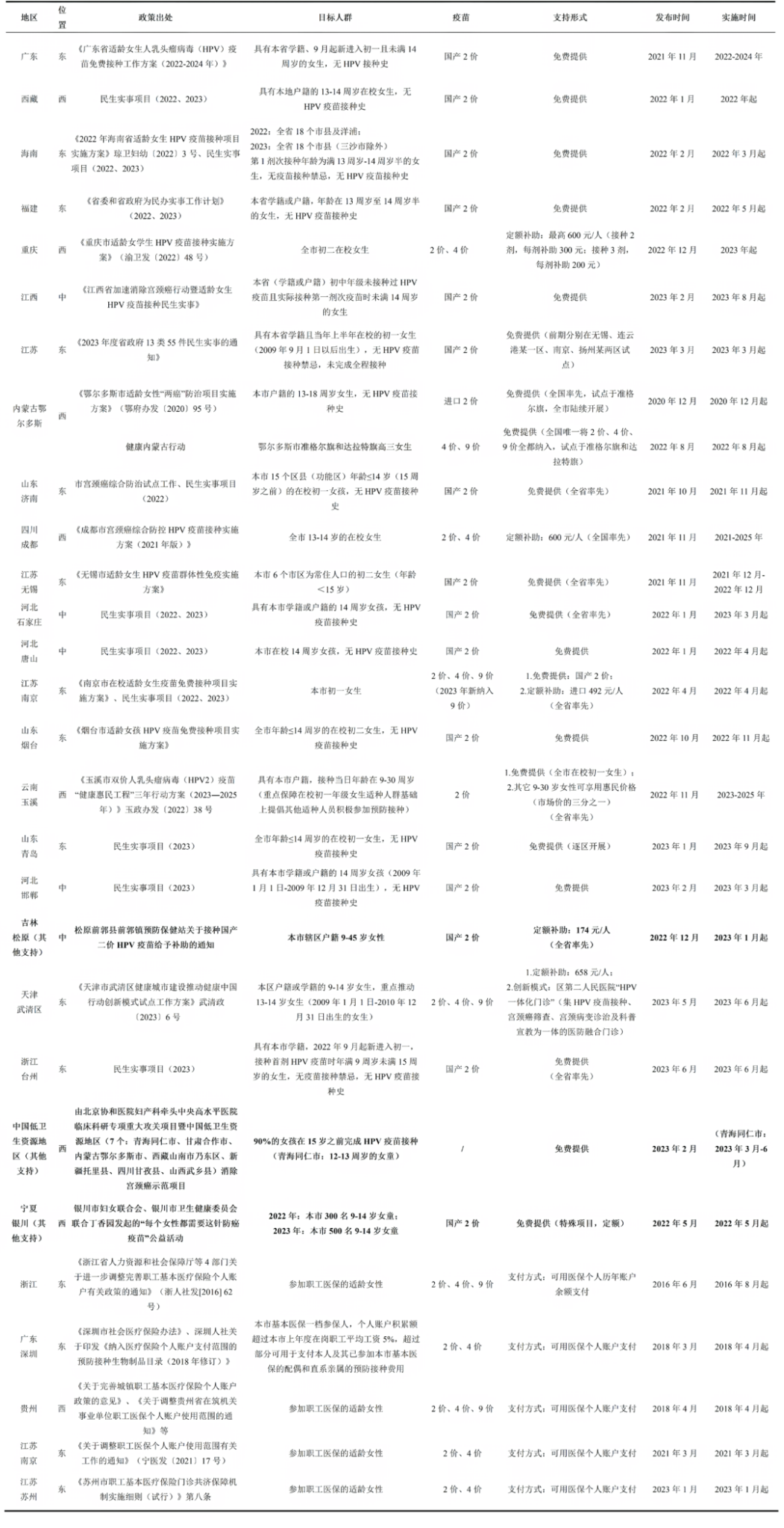

One study compared the cost-effectiveness of 61 intervention strategies, including a combination of various screening methods at different frequencies with and without vaccination and vaccination alone. The study found that HPV vaccination combined with HPV screening every five years was the most cost-effective compared to no intervention, with an ICER of $21,799 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cost-effectiveness frontiers (Left) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (right) for all intervention strategies

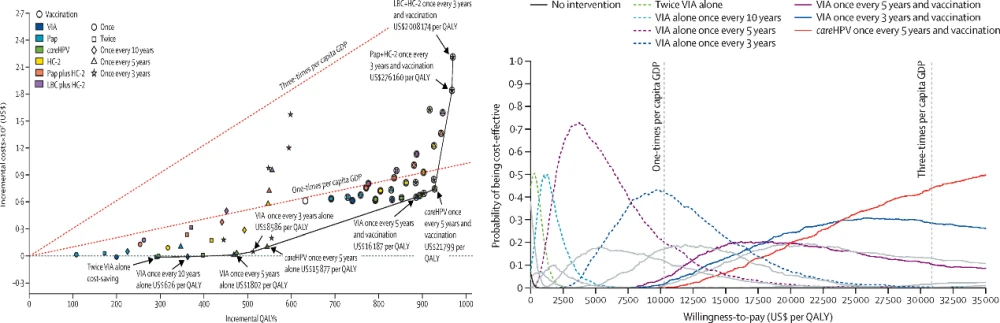

The same study also evaluated the correlation between vaccine pricing and the cost-effectiveness of various interventions. The findings indicate that as vaccine prices decrease, cost-effectiveness improves (Figure 2). When the cost of vaccines is capped at less than $50 for two doses, any strategy integrating HPV vaccination for girls aged 9 to 14 with cervical cancer screening tends to be more cost-effective than screening alone at lower willingness-to-pay thresholds (around the per capita GDP). Furthermore, vaccination combined with a visual acetic acid screening method conducted every five years proved the most cost-effective approach. If the vaccine price is less than $10 for two doses, it becomes more cost-effective than screening alone at any willingness-to-pay threshold.

Figure 2. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for all strategies at various costs of vaccination

Key factors affecting HPV vaccines’ cost-effectiveness

Factors such as economic development level, vaccine type, the target population, and HPV infection prevalence could affect the vaccine’s cost-effectiveness outcomes. For example, a systematic review found that although there was heterogeneity in the methods used to measure cost-effectiveness, 10 of the 12 included studies concluded that the nine-valent HPV vaccine was cost-effective, and 2 studies did not [9]. Another systematic review indicated that it was unclear if the nine-valent vaccine was more cost-effective than the previously marketed bivalent and quadrivalent vaccines due to the unclear pricing of the nine-valent vaccine [10]. In these systematic reviews, researchers found that factors such as vaccine type, price, vaccination coverage, and target population are important parameters affecting the outcome of HPV vaccine cost-effectiveness analysis, with vaccine cost being the most important factor affecting the sensitivity analysis.

HPV vaccine types and price

The market-available vaccines target different HPV genotypes, and cost-effectiveness results vary due to differences in vaccine coverage and vaccine prices in different regions. For example, a Singapore study found that the ICER for bivalent vaccination was $10,392 Singapore dollar (SGD) SGD/QALY and that for quadrivalent vaccination was $9,071 SGD/QALY compared to no vaccination [11], while a UK study found that if the price per dose of the bivalent vaccine was 22-41% lower than that of the quadrivalent vaccine, the two could produce the same cost-effectiveness [12].

Age of vaccine recipients

Most studies concluded that HPV vaccination for girls aged 9-14 years and for women who are not yet sexually active are the most cost-effective interventions. In a systematic review of studies focusing on the cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination for adult women aged 26 years and older, four of six studies found that HPV immunization was not cost-effective for adult women aged 26 years and older (ICER: $65,000-$192,000/QALY) [12]. One UK study showed that HPV vaccination in this population was only cost-effective vaccine price was below £20/dose and lifetime vaccine protection for women when no loss of immunity over time was considered [12]. A study from Lao PDR indicated that the vaccination could be cost-effective with a catch-up vaccination for women up to age 75 years, and the existing schoolgirls vaccination program was strongly subsidized [12].

Gender of vaccine recipients

HPV vaccination of males can indirectly reduce the rate of infection in the population with whom they have sex while reducing lesions such as genital warts. Some countries (e.g., the United States and Australia) have expanded the vaccination population to boys aged 9-14. However, evidence on the cost-effectiveness of expanding HPV vaccination to boys or conducting gender-neutral HPV vaccination programs is sparse and inconsistent.

A systematic review of articles published between 2005 and 2015 explored the economic evaluation of HPV vaccination for boys [13]. Among the 15 studies included, 53% showed that HPV vaccination among boys was cost-effective, and 7% found it was potentially cost-effective. In contrast, another systematic review covering 17 developed country studies came to the opposite conclusion, noting that there is little evidence that extending HPV vaccination programs to heterosexual men is cost-effective, but targeted vaccination of men having sex with men (MSM) is a cost-effective option (although the specific implementation of this strategy needs to be further explored) [14]. Similar conclusions were supported by another systematic review that included four studies that explored HPV vaccination in the MSM population, two of which found that HPV vaccination targeting the MSM group was cost-effective in preventing anal cancer-related disease [15]. Another recently published systematic review study included nine studies conducted in high-income countries (such as Spain, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and Canada), comparing the gender-neutral and female-only vaccination strategies. Four of the studies demonstrated a two-dose gender-neutral HPV vaccination strategy was more cost-effective compared to a female-only vaccination program [16].

Geographic Areas

Based on WHO recommendations, an intervention program is cost-effective when the cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) saved is less than three times the GDP per capita. Hence, the economic level of the geographic area targeted for vaccination impacts the cost-effectiveness calculation. A systematic review of 12 papers on the economic evaluation of HPV vaccines in low- and middle-income countries such as Laos, Malaysia, Iran, India, Thailand, South Africa, and Brazil shows that in 11 of the included studies, HPV vaccination among girls aged 9-14 years was cost-effective, Factors impacting cost-effectiveness include age, intervention coverage, and vaccine dose administered. Vaccination is cost-effective as a stand-alone intervention if coverage reaches 70-100% [1].

Implementation

A retrospective study focusing on HPV vaccination in low- and middle-income countries found that combining HPV vaccination with visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) screening was the most cost-effective intervention compared to HPV vaccination or screening alone [17]. In addition, increasing evidence supports that the antibody titers produced after 2-dose bivalent vaccination were comparable to the 3-dose schedule, while a Malaysian study predicted a savings of nearly $57.29 million by applying a 2-dose schedule [18]. New evidence also suggests that HPV single-dose regimens are comparable to two- and three-dose regimens. Although there is a lack of evidence on the single-dose regimen’s long-term protection, the World Health Organization revised its HPV vaccine position paper in December 2022 to recommend a single-dose regimen for females between the ages of 9 and 20 years [19].

A modeling study showed that two doses of routine vaccination of 14-year-olds would be the best cost-saving strategy for future national immunization programs, compared with no vaccination, in a supply-constrained and on-label use scenario (NND:150-220, net cost savings: $15,164 million – $22,034 million, ROI: 7-14, depending on vaccine type). The study also found that if the WHO-recommended single-dose vaccination schedule were approved in China, redistributing the remaining second dose of vaccine in the routine vaccination cohort to add a catch-up vaccination for the 20-years-old would be the most efficient strategy (NNDs:73-107), and would be even more cost-saving compared to implementing routine single-dose vaccination for 14-year-olds only (Net Cost Savings: US$4,127 million-US$6,035 million, ROI:19-37) [20].

Content Reviewer: Kelly Hunter, Menglu Jiang

Page Editor: Jiaqi Zu

References:

- Okeah BO, Ridyard CH: Factors influencing the cost-effectiveness outcomes of HPV vaccination and screening interventions in low-to-middle-income countries (LMICs): a systematic review. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 2020, 18:641-654.

- Wang H, Zhao F, Zhao Y: Expert consensus on immune prevention of human papillomavirus-related diseases such as cervical cancer. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2019, 53(8):761-803.Mo X, Tobe RG, Wang L, Liu X, Wu B, Luo H, Nagata C, Mori R, Nakayama T: Cost-effectiveness analysis of different types of human papillomavirus vaccination combined with a cervical cancer screening program in mainland China. BMC infectious diseases 2017, 17(1):1-12.

- Jit M, Brisson M, Portnoy A, Hutubessy R: Cost-effectiveness of female human papillomavirus vaccination in 179 countries: a PRIME modelling study. The Lancet Global Health 2014, 2(7):e406-e414.

- Liu Y-J, Zhang Q, Hu S-Y, Zhao F-H: Effect of vaccination age on cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination against cervical cancer in China. BMC Cancer 2016, 16(1):164.

- Zhang Q, Liu Y-J, Hu S-Y, Zhao F-H: Estimating long-term clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HPV 16/18 vaccine in China. BMC cancer 2016, 16(1):848-848.

- Mo X, Gai Tobe R, Wang L, Liu X, Wu B, Luo H, Nagata C, Mori R, Nakayama T: Cost-effectiveness analysis of different types of human papillomavirus vaccination combined with a cervical cancer screening program in mainland China. BMC Infect Dis 2017, 17(1):502.

- Zou Z, Fairley CK, Ong JJ, Hocking J, Canfell K, Ma X, Chow EP, Xu X, Zhang L, Zhuang G: Domestic HPV vaccine price and economic returns for cervical cancer prevention in China: a cost-effectiveness analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2020, 8(10):e1335-e1344.

- Mahumud RA, Alam K, Keramat SA, Ormsby GM, Dunn J, Gow J: Cost-effectiveness evaluations of the nine-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: Evidence from a systematic review. PloS one 2020, 15(6):e0233499.

- Ng SS, Hutubessy R, Chaiyakunapruk N: Systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: nine-valent vaccine, gender-neutral and multiple age cohort vaccination. Vaccine 2018, 36(19):2529-2544.

- Lee VJ, Tay SK, Teoh YL, Tok MY: Cost-effectiveness of different human papillomavirus vaccines in Singapore. BMC Public Health 2011, 11(1):1-11.

- Jit M, Choi YH, Edmunds WJ: Economic evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United Kingdom. Bmj 2008, 337.

- Soe NN, Ong JJ, Ma X, Fairley CK, Latt PM, Jing J, Cheng F, Zhang L: Should human papillomavirus vaccination target women over age 26, heterosexual men and men who have sex with men? A targeted literature review of cost-effectiveness. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2018, 14(12):3010-3018.

- Sinisgalli E, Bellini I, Indiani L, Sala A, Bechini A, Bonanni P, Boccalini S: HPV vaccination for boys? A systematic review of economic studies. Epidemiol Prev 2015, 39(4 Suppl 1):51-58.

- Yahia M-BBH, Jouin-Bortolotti A, Dervaux B: Extending the human papillomavirus vaccination programme to include males in high-income countries: a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness studies. Clinical drug investigation 2015, 35(8):471-485.

- Setiawan D, Wondimu A, Ong K, Van Hoek AJ, Postma MJ: Cost Effectiveness of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Men Who have Sex with Men; Reviewing the Available Evidence. PharmacoEconomics 2018, 36(8):929-939.

- Linertová R, Guirado-Fuentes C, Medina JM, Imaz-Iglesia I, Rodríguez-Rodríguez L, Carmona-Rodríguez M: Cost-effectiveness of extending the HPV vaccination to boys: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021.

- Abidi S, Labani S, Singh A, Asthana S, Ajmera P: Economic evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccination in the Global South: a systematic review. International Journal of Public Health 2020:1-15.

- Li Y, Chen S, Huang X, Fang Y, Zhao Q: Clinical efficacy and economics of human papillomavirus vaccine. Modern Preventive Medicine, 2018, 45(15).

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2022, December 20). WHO updates recommendations on HPV vaccination schedule [Press release]. WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/20-12-2022-WHO-updates-recommendations-on-HPV-vaccination-schedule

- You, T., Zhao, X., Hu, S., Gao, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Qiao, Y., Jit, M., & Zhao, F. (2022). Optimal allocation strategies for HPV vaccination introduction and expansion in China accommodated to different supply and dose schedule scenarios: A modelling study. EClinicalMedicine, 56, 101789.