Global Rotavirus Disease Burden

Incidence

Almost every child will experience at least one rotavirus infection before the age of 5 ¹. Rotavirus infection is the leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide, especially among children under 5 years of age². RVGE typically presents acutely, with main symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, often accompanied by fever. In 2016, the global incidence of RVGE caused by rotavirus-related diarrhea was estimated to be 258 million cases². The incidence rate of rotavirus was 80‰ (95% CI: 67.1‰–94.1‰), and for children under 5 years of age, the incidence rate was 408.6‰ (95% CI: 311.6‰–533.1‰) ³.

Mortality

In 2016, diarrhea was the eighth leading cause of death across all age groups³. According to World Health Organization (WHO) data released in 2024, diarrhea is the third leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age, causing about 443,832 child deaths worldwide each year⁷. Globally, diarrhea is primarily caused by contaminated water and food, with mortality rates highest in countries with lower socio-economic development.

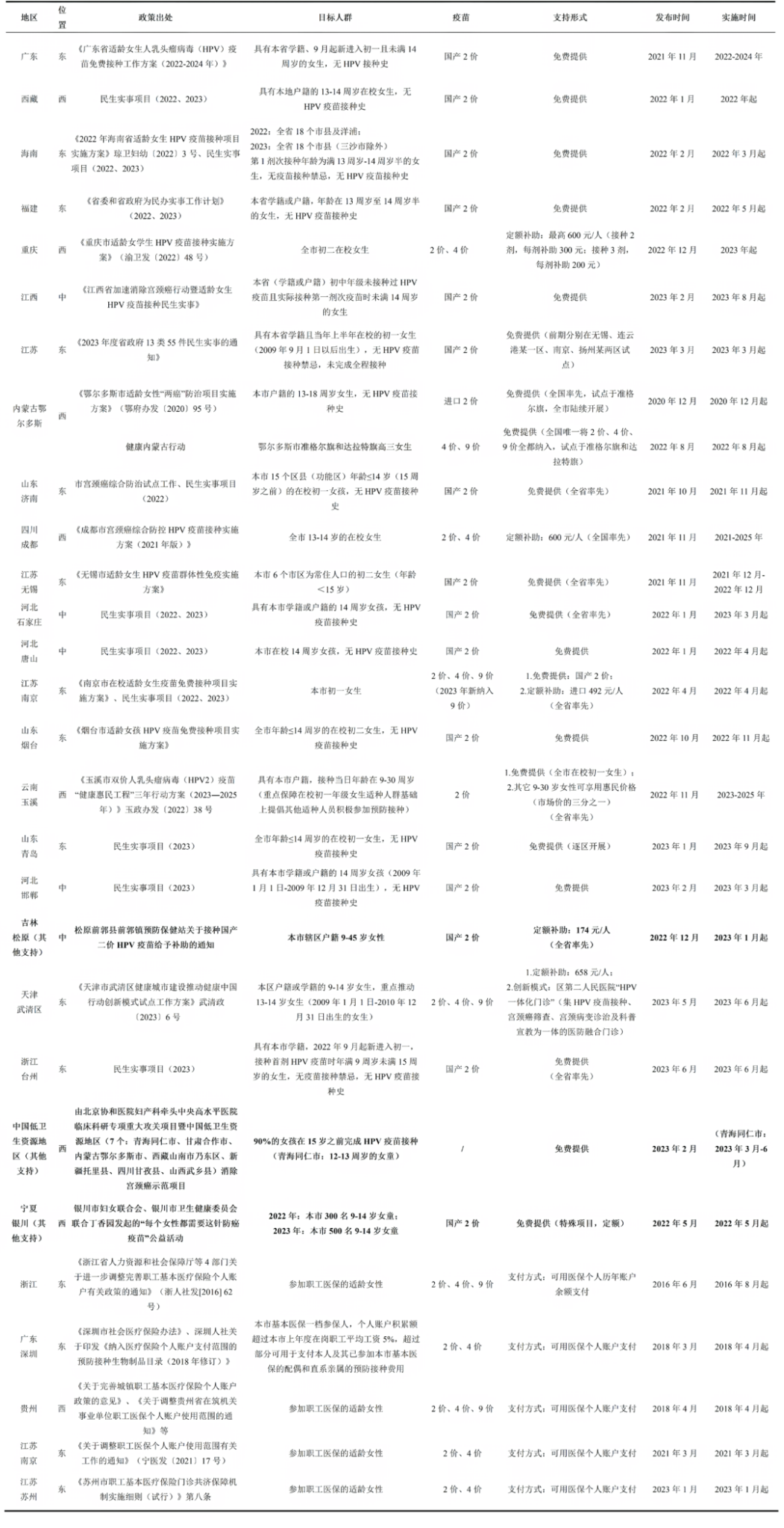

U5MR=under-5 mortality rate. ATG=Antigua and Barbuda. VCT=Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. LCA=Saint Lucia. TTO=Trinidad and Tobago. Isl=Islands. FSM=Federated States of Micronesia. TLS=Timor-Leste.

Source: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30362-1

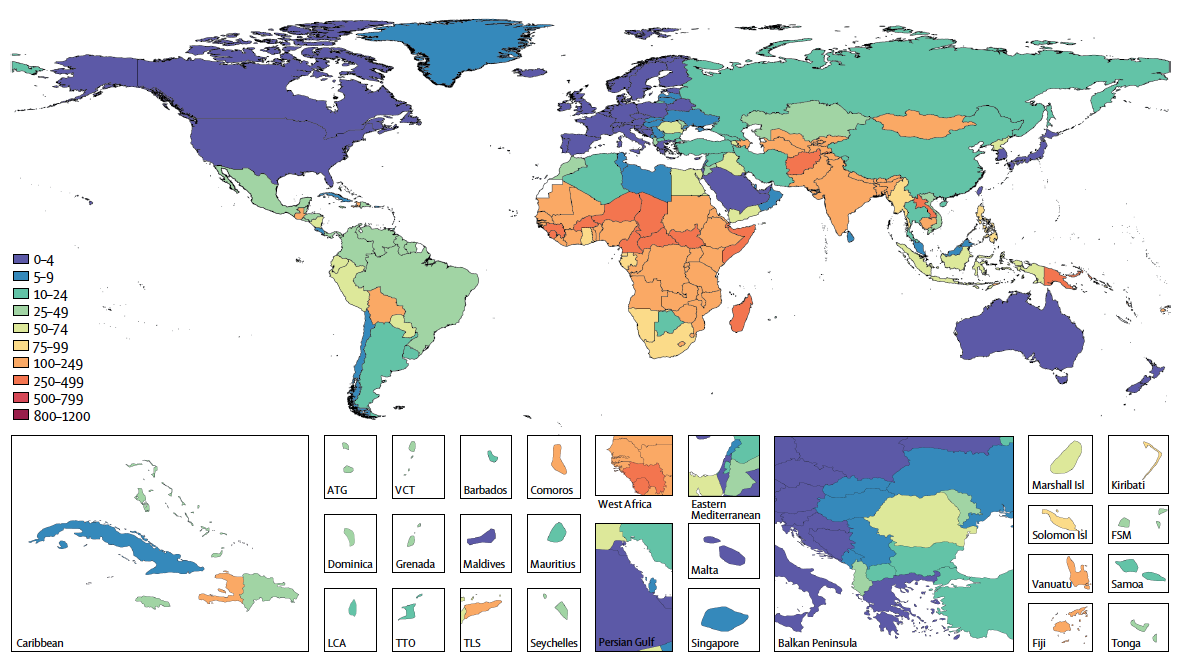

Rotavirus infection remains the leading cause of diarrhea-related deaths worldwide, with the highest mortality observed among children under five. However, in high to middle sociodemographic index (SDI) regions, mortality is higher in individuals aged 70 years or older³, ⁸. Based on the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study, rotavirus infection accounted for 19.11% of all diarrhea-related deaths globally. Although this is a decrease from 26.95% in 1990, rotavirus remains the leading cause of mortality among 13 pathogens that cause diarrhea-related deaths⁸. In 2019, the global mortality rate from rotavirus was estimated to be 3 per 100,000 people. For children under 5 years of age, the rate was 22.9 per 100,000; this amounted to an estimated 152,000 deaths in children under 5 years of age, accounting for 64.68% of all rotavirus-related deaths⁹. In addition, older adults aged 70 years and above are at elevated risk of mortality from rotavirus infection. Studies have reported an increasing trend in rotavirus-related mortality among individuals aged 70 and above in relatively high SDI regions between 1990 and 2019. In 2019, the mortality rate for rotavirus infection in individuals aged 70+ was higher than in children under 5 years of age in these countries, likely due to the rapid aging population, weakened immunity, and underlying diseases in older individuals, which increase susceptibility to infectious diseases⁸, ¹⁰.

Since 1990, most countries have seen a decline in rotavirus-related mortality, though disparities remain between regions. Following the global introduction of rotavirus vaccines and improvements in sanitation and water infrastructure, rotavirus-related deaths have decreased from 659,053 in 1990 to 235,331 in 2019⁸. However, low SDI regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, continue to experience disproportionately high mortality rates from rotavirus infections (Figure 3.2), due to factors such as lower hygiene standards, malnutrition, and inadequate access to medical care⁸.

Source: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01898-9

In 2013, WHO introduced “The integrated Global Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD)”, which aimed to reduce the global incidence of severe diarrhea preventable by 75% by 2025 compared to 2010, and to lower the mortality rate of children under 5 years of age from diarrhea to fewer than 1 death per 1,000 live births by 2025¹¹. However, based on estimates of rotavirus-related diarrhea mortality in 2019, there is significant efforts are still required to achieve this target.

Outpatient and Inpatient Burden

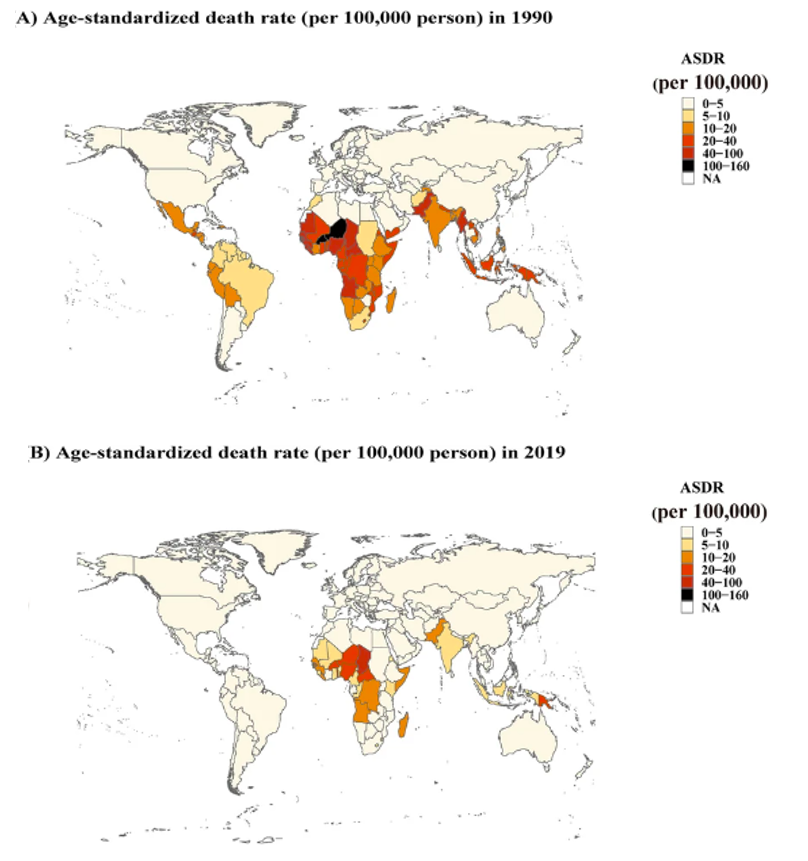

Rotavirus infection poses a significant burden on both outpatient and inpatient services and remains one of the leading causes of diarrhea-related hospitalizations in children. A systematic review on Asian countries found that from 2000 to 2011, the incidence of outpatient visits for rotavirus-related gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age ranged from 5.6 to 45.3 cases per 1,000 children annually, with hospitalization rates ranging from 2.1 to 20.0 per 1,000 children with hospitalization rates ranging from 2.1 to 20.0 cases per 1,000 children⁴. A further systematic review estimated that in 2019, there were approximately 1.76 million hospitalizations worldwide due to rotavirus infection (IQR: 1,422,645–2,925,372); hospitalization rates were highest in countries with low mortality, likely reflecting differences in healthcare access and health-seeking behaviors of medical services between different population groups⁵. In countries where rotavirus vaccines were not included in the immunization schedule, approximately 40% of hospitalizations for diarrhea in children under 5 years of age were due to rotavirus (Figure3.3)⁶. Another systematic review reported a hospitalization rate of 0.6 episodes per child-year for rotavirus-related diarrhea among unvaccinated children under five12.

Source: Rotavirus Organization of Technical Allies6

Socio-Psychological Burden

Rotavirus infection imposes a considerable socio-psychological burden, adversely affecting the quality of life of both children and their caregivers. Parents of children infected with rotavirus often experience noticeable psychological stress, including elevated levels of anxiety and concern, consequently diminishing the overall family quality of life 13-15. Diarrhea and hospitalization caused by rotavirus infection led to a reduction in both the child’s and caregiver’s quality of life, with some studies showing that children with rotavirus-related diarrhea have a lower quality of life compared to children with non-rotavirus diarrhea¹⁶,¹⁷.

Global Economic Burden of Rotavirus

The healthcare utilization associated with RVGE imposes a substantial global economic burden. In Asian countries, the direct medical costs caused by RVGE range from $20 to $2,142 per case (adjusted to 2009 USD)¹⁸. A study conducted on 73 countries supported or eligible for support by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi) estimated that the total outpatient cost caused by RVGE (including direct medical expenses, non-medical costs, and indirect costs) averaged $16.81 per case (adjusted to 2015 USD), while the cost of hospitalization was $90.68 per case¹⁹. Another study of 63 middle-income countries not eligible for Gavi funding estimated the average cost per outpatient case for RVGE at $23.2 per case (adjusted to 2018 USD), while the average cost for hospitalization was $352 per case²⁰.

China’s Rotavirus Disease Burden

Incidence

Rotavirus infection remains the leading cause of diarrhea in China, primarily affecting children under 5 years of age. In 2014-2015, viral diarrhea accounted for more than 90% of all reported diarrhea cases in China, with rotavirus infections causing 95.7% of diarrhea cases in 2014 and 93.1% in 2015¹⁸. From 2009 to 2020, the National Science and Technology Major Project Infectious Disease Surveillance Platform recorded data from 252 sentinel hospitals across 28 provinces, detecting 21,872 rotavirus-positive cases, of which 84.3% of these cases being in children under 5 years of age²². A meta-analysis found that between 2011 and 2018, 34.0% (95% CI: 31.3%-36.8%) of children under 5 years of age presenting for diarrhea were diagnosed with rotavirus; of these, 39.7% (95% CI: 34.2%-45.6%) required hospitalization, which exceeded the 23.9% (95% CI: 18.1%-30.9%) the outpatient proportion²³.

Nationwide, the reported incidence of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 5 years of age has shown a fluctuating upward trend. Rotavirus is classified and reported under China’s Category C notifiable infectious diseases, specifically under the subgroup “other infectious diarrhea”. From 2005 to 2018, a total of 820,588 cases of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 5 years of age were reported, with an average annual incidence rate of 63.7 per 100,000, which increased from 8.4 per 100,000 in 2005 to 178.1 per 100,000 in 2018 (with the number of reporting provinces rising from 17 to 30)²⁴.

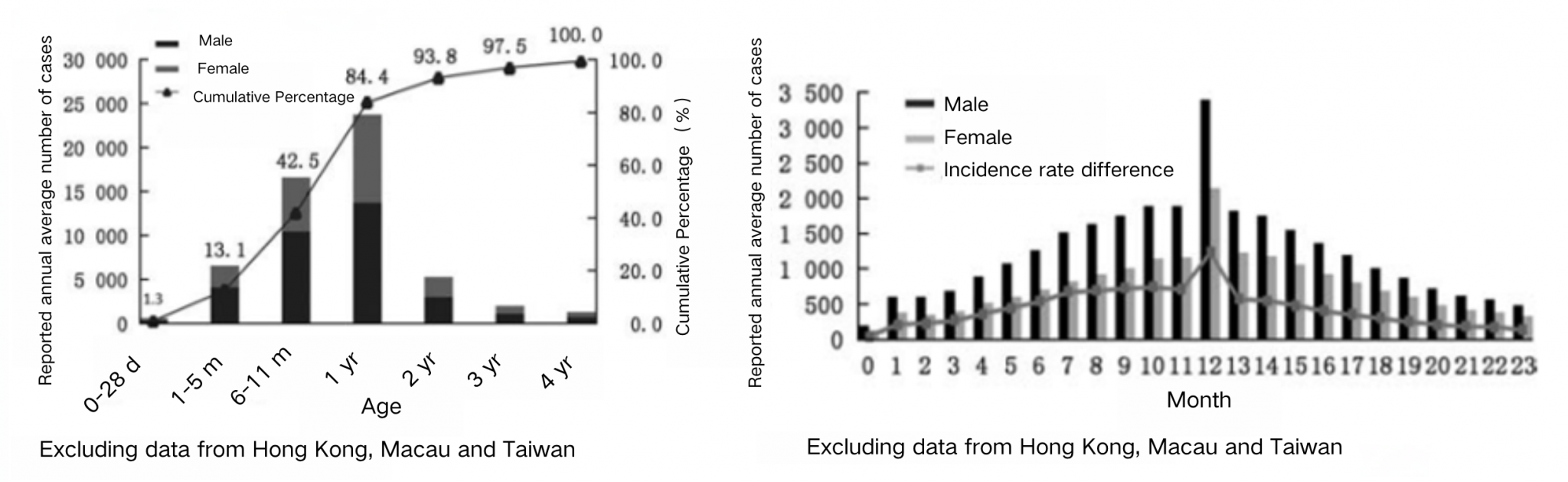

Rotavirus-induced diarrhea in children under 5 years of age shows both age and gender distribution characteristics, with the highest infection rates observed in infants aged 6 months to 2 years, and higher rates in males than females. The reported number of cases in infants under 12 months increases overall with age, peaking between 11 and 13 months (163,947 cases), after which the number of cases decreases. Children under 5 months of age accounted for 13.1% (107,845 cases), and those aged 6 months to 2 years accounted for 70.3% (576,874 cases). The peak incidence was in children aged 11–13 months. Gender distribution shows higher rates in males than females, with statistical significance²⁴. A meta-analysis further found that the RV positivity rate among children under 5 years of age visiting for diarrhea was highest in the 12–23 months age group, with a positivity rate of 40.1%, followed by 33.1% in the 6-11 months age group²³. Additionally, about 22% of children under two with diarrhea have moderate to severe diarrhea each year, significantly increasing the risks of developmental delays and mortality²⁵.

Source: Luo HM, Ran L, Meng L, Lian YY, Wang LP. Analysis of epidemiological characteristics of report cases of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 5 years old in China, 2005-2018. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;54(2):181-186. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2020.02.013.

Mortality

Currently, the number of deaths from diarrhea-related diseases in children under 5 years of age in China is relatively low, but rotavirus infection remains the leading cause of diarrhea-related mortality. With the development of the economy and improvements in the healthcare and public health systems, the overall mortality rate in children has shown a decreasing trend. In 2016, the national mortality rate for children under 5 years of age was 10.2‰, with 1,342 deaths from diarrhea in children under 5 years of age (95% CI: 1102-1659), corresponding to a mortality rate of 2.2 per 100,000 population (95% CI: 1.8-2.7)³,²⁶. According to cause-of-death data from the 2021 National Mortality Surveillance System, only 20 deaths in children under 5 years of age were attributed to diarrhea-related diseases, accounting for about 0.3% of all deaths²⁷. However, rotavirus infection has consistently been the leading cause of diarrhea-related deaths. From 2003 to 2012, a total of 127,539 deaths from were reported among Chinese children under 5 years of age years of age, of whom an estimated 53,559 (42%) had illness attributable to rotavirus²⁸. Between 2017 and 2021, there were 2,171 viral diarrhea outbreaks reported nationwide, 15 of which were rotavirus-related, resulting in 3 deaths, accounting for 75% of all viral diarrhea-related deaths (4 deaths in total)²⁹.Since 2000, the mortality rate due to rotavirus has shown an overall decreasing trend. In 2002, rotavirus caused approximately 13,400 deaths in children under 5 years of age in China³⁰.The annual number of deaths of children under 5 years from rotavirus diarrhea decreased by 73.5% (from 10,531 in 2003 to 2791 in 2012; during this same time, the mortality rate from rotavirus diarrhea declined by 74.2%, from 0.66 per 1000 live births in 2003 to 0.17 deaths per 1000 live births in 2012 ²⁸. Improvements in healthcare services, vaccination, clean water supply, and sanitary toilets may have contributed to this decrease in diarrhea-related mortality.

There is a rural-urban and east-central-west disparity in the rotavirus-related mortality rate in China. Mortality due to rotavirus diarrhea largely occurred in rural areas (93%), where the mortality rates (0.33 per 1,000 live births in 2012) were 11 times greater than in urban areas (0.03 per 1,000 live births in 2012) ²⁸. Despite the higher incidence of rotavirus infections in the southern regions, there are disparities in mortality rates between eastern, central, and western regions, with western and central provinces showing higher mortality rates (Figure 3.5). Although the current mortality rates for diarrhea and rotavirus-related deaths in China are low, these findings indicate that attention should still be given to the severity of disease caused by rotavirus across different regions with varying economic development levels.

Source: Zhang J, Duan Z, Payne DC, et. al. Rotavirus-specific and overall diarrhea mortality in Chinese children younger than 5 years: 2003 to 2012. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2015 Oct 1;34(10):e233-7. DOI: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000799

Outpatient and Inpatient Burden

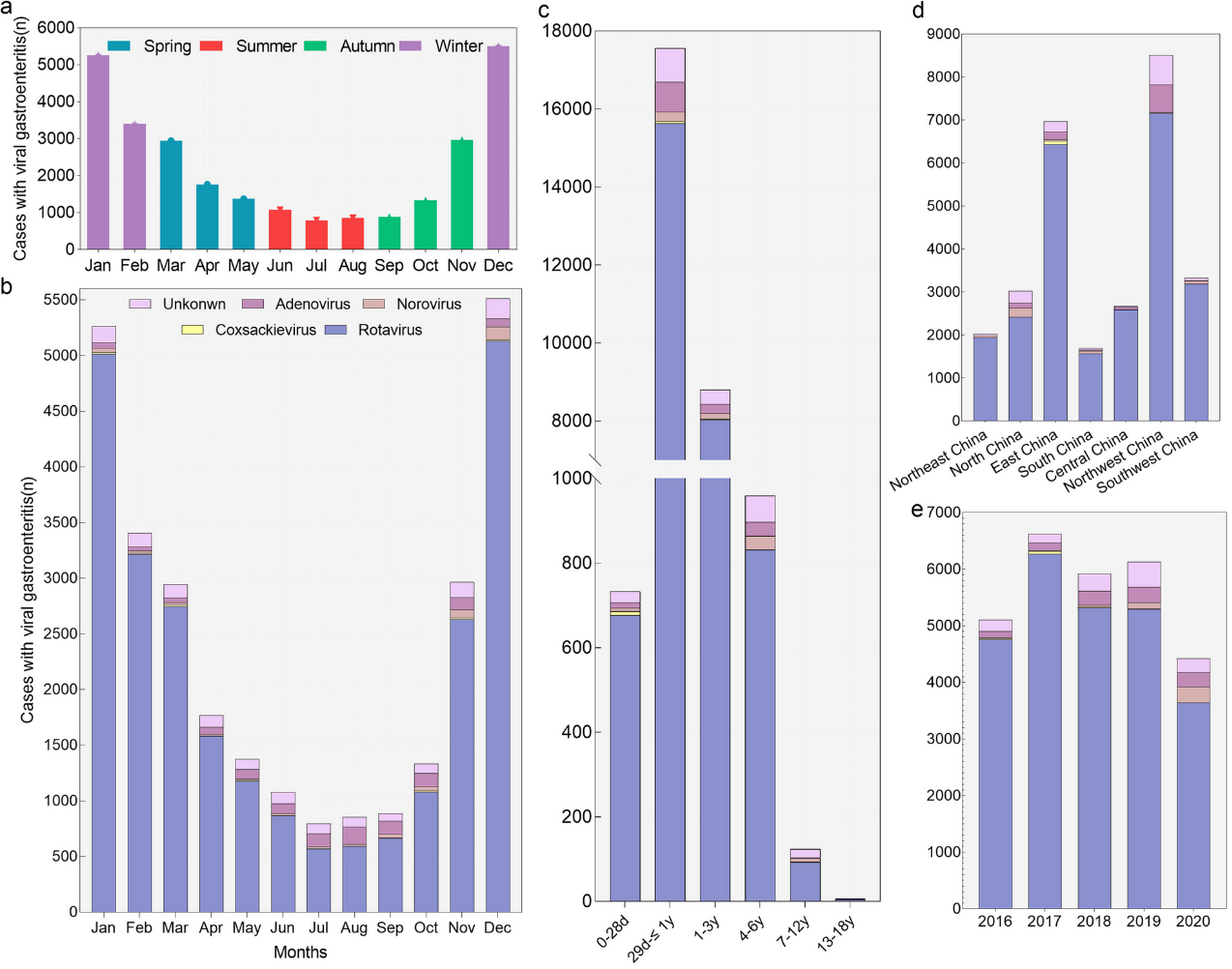

Rotavirus infection is a significant contributor to outpatient visits and hospitalizations for diarrhea in China, placing a significant burden on healthcare services through outpatient visits and hospitalizations. From 2009 to 2020, rotavirus infections accounted for 19% of outpatient diarrhea cases in 252 hospitals across 28 provinces in China²². Rotavirus is also a major cause of hospitalization for pediatric d diarrhea in China. A retrospective study based on 27 hospitals from 2016 to 2020 showed that 89.7% of 28,189 hospitalized viral gastroenteritis cases were rotavirus-positive, exceeding the detection rates of other viral pathogens³¹. The hospitalization burden from rotavirus infection is predominantly observed in children under three years of age (Figure 3.6).

Panel (a) shows the number of hospitalized children with viral gastroenteritis in different seasons. Panel (b) shows the distribution of pathogens in different months. Seasons were based on months as follows: Winter, January through March; Spring, April through June; Summer, July through September; Fall, October through December. Panel (c)-(e) show the pathogen distribution in different age groups, years, and regions of China. The definition of “Unknown” is that children with viral gastroenteritis were for an unspecified viral cause.

Source: Li F, Guo L, Li Q, Xu H, Fu Y, Huang L, Feng G, Liu G, Chen X, Xie Z. Changes in the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of viral gastroenteritis among hospitalized children in the Mainland of China: a retrospective study from 2016 to 2020. BMC pediatrics. 2024 May 4;24(1):303. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04776-1

Since 1998, China has been establishing a sentinel surveillance network for rotavirus among children under 5 years of age hospitalized with diarrhea. By 2021, the RV sentinel network had expanded to cover 42 sentinel hospitals across 31 provinces (including autonomous regions and municipalities)². A nationwide study based on this surveillance network found that from 2011 to 2019, 47,386 children under 5 years of age hospitalized for diarrhea were sampled, with 14,952 cases (31.55%) testing positive for rotavirus³². In 2019, 1,247 out of 5,038 diarrhea hospitalization cases in children under 5 years of age from 20 provinces were rotavirus-positive (24.75%). The highest rotavirus positivity rate was observed in the sentinel site in Henan Province (182/338, 53.85%)³³. The study also found rural-urban disparities in the rotavirus positivity rate among hospitalized children: the positivity rate in rural areas (28.53%) was higher than in urban areas (22.71%). There were also seasonal differences: the positivity rate was highest in winter (42.43%) and lowest in summer (9.76%)³².

A study based on data from Hangzhou showed that, for children under 5 years of age, the incidence of rotavirus-associated outpatient visits in 2007-2008 was approximately 20.1 cases per 1,000, and hospitalizations were 2.1 per 1,000; the incidence of rotavirus-associated outpatient visits and hospitalizations for children under 2 years of age was even higher, at 39.1 per 1,000, and 4.1 per 1,000, respectively.34 The estimated number of rotavirus-associated outpatient visits for children under 5 years in China were 3.48 million in 2007, and 1.16 million in 2013; hospitalizations were estimated to be 220,000 in 2007 and 110,000 in 20132,35 .

Socio-Psychological Burden

Current research on the socio-psychological burden caused by rotavirus infections in China remains limited, highlighting the need for further investigation.

Economic Burden of Rotavirus in China

China faces a substantial economic burden from rotavirus infections, reported as the highest RVGE-related economic burden in Asia ³⁶. A study conducted in three hospitals in Shandong, Henan, and Gansu provinces investigated the direct medical costs of outpatient and inpatient visits for diarrhea caused by rotavirus from 2020 to 2021. The study found that the average cost per outpatient and inpatient case due to rotavirus infection was 389.85 CNY and 4,131.10 CNY, respectively³⁷.

A meta-analysis report calculated the pooled total cost from the social’s perspective per case of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age in China at approximately 2,025 CNY (including direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, and indirect costs), assuming 50% reimbursement of direct medical costs, resulting in an average private expenditure of approximately 1,482 CNY (Table 3.1)³⁸.

Table 3.1: Pooled Costs due to RV AGE Treated at Outpatient and Inpatient among Children under 5 years of age

| Cost (CNY) | Outpatient | Inpatient | Total |

| n = 3328 cases | n = 2757 cases | n = 6085 cases | |

| Direct Costs (Mean, 95% CI) | 278 (236–320) | 2784 (2268–3299) | 1391 (1038–1745) |

| Direct Medical Costs (Mean, 95% CI) | 180 (154–208) | 2220 (1888–2552) | 1087 (806–1369) |

| Direct Non-Medical Costs (Mean, 95% CI) | 121 (88–154) | 644 (447–841) | 365 (257–472) |

| Indirect Costs (Mean, 95% CI) | 275 (225–325) | 846 (910–1643) | 713 (527–900) |

| Total Social Costs (Mean, 95% CI) | 526 (45–618) | 3900 (3064–4737) | 2025 (1532–2518) |

| Total Private Costs (Mean, 95% CI) | 47 (349–521) | 2790 (2101–3480) | 1482 (1114–1849) |

Content Editor: Siqi Jin, Ziqi Liu

Page Editor: Ziqi Liu

References

- WHO. Rotavirus vaccines: WHO position paper. July 2021. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2021, 96(28):301-320. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WER9628

- Writing Group for Expert Consensus on Rotavirus Gastroenteritis. Expert consensus n immunoprophylaxis of childhood rotavirus gastroenteritis (2024 version). Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2024;58(0):1-33. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20231220-00472

- Troeger C, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, Rao PC, Cao S, Zimsen SR, Albertson SB, Stanaway JD, Deshpande A, Abebe Z, Alvis-Guzman N. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2018 Nov 1;18(11):1211-28. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30362-1

- Kawai K, O’Brien MA, Goveia MG, Mast TC, El Khoury AC. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis and distribution of rotavirus strains in Asia: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012 Feb 8;30(7):1244-54.

- Benjamin D Hallowell, Tyler Chavers, Umesh Parashar, Jacqueline E Tate, Global Estimates of Rotavirus Hospitalizations Among Children Below 5 Years in 2019 and Current and Projected Impacts of Rotavirus Vaccination, Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, Volume 11, Issue 4, April 2022, Pages 149–158, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piab114

- Rotavirus Organization of Technical Allies. The epidemiology and disease burden of rotavirus. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-02/rota-brief3-burden2022ax.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2024, March 7). Diarrhoeal disease. World Health Organization. Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease

- Du Y, Chen C, Zhang X, Yan D, Jiang D, Liu X, Yang M, Ding C, Lan L, Hecht R, Zhu C. Global burden and trends of rotavirus infection-associated deaths from 1990 to 2019: an observational trend study. Virology journal. 2022 Oct 20;19(1):166. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01898-9

- Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Abdollahi M. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1204-22. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

- Ciabattini A, Nardini C, Santoro F, Garagnani P, Franceschi C, Medaglini D. Vaccination in the elderly: the challenge of immune changes with aging. Semin Immunol. 2018;40:83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2018.10.010.

- World Health Organization/The United Nations Children′s Fund (UNICEF) 2013. Ending Preventable Child Deaths from Pneumonia and Diarrhoea by 2025. The integrated Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD) [Z]. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241505239

- Chavers T, Cates J, Burnett E, Parashar UD, Tate JE. Indirect protection from rotavirus vaccines: a systematic review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2024 Aug 21. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2024.2395534.

- Aldeán JÁ, Aristegui J, López-Belmonte JL, Pedrós M, Sicilia JG. Economic and psychosocial impact of rotavirus infection in Spain: a literature review. Vaccine. 2014 Jun 24;32(30):3740-51.

- Laizane G, Kivite A, Stars I, Cikovska M, Grope I, Gardovska D. Health-related quality of life of the parents of children hospitalized due to acute rotavirus infection: a cross-sectional study in Latvia. BMC pediatrics. 2018 Dec; 18:1-8.

- Carias C, Hu T, Chen YT. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis on caregivers: Findings from a systematic literature review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2022 Nov 30;18(5):2047545. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2047545

- Rochanathimoke O, Riewpaiboon A, Postma MJ, Thinyounyong W, Thavorncharoensap M. Health related quality of life impact from rotavirus diarrhea on children and their family caregivers in Thailand. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2018 Mar 4;18(2):215-22.

- Marlow R, Finn A, Trotter C. Quality of life impacts from rotavirus gastroenteritis on children and their families in the UK. Vaccine. 2015 Sep 22;33(39):5212-6.

- Kawai K, O’Brien MA, Goveia MG, Mast TC, El Khoury AC. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis and distribution of rotavirus strains in Asia: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012 Feb 8;30(7):1244-54.

- Debellut F, Clark A, Pecenka C, Tate J, Baral R, Sanderson C, Parashar U, Kallen L, Atherly D. Re-evaluating the potential impact and cost-effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in 73 Gavi countries: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2019 Dec 1;7(12):e1664-74. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30439-5

- Debellut F, Clark A, Pecenka C, Tate J, Baral R, Sanderson C, Parashar U, Atherly D. Evaluating the potential economic and health impact of rotavirus vaccination in 63 middle-income countries not eligible for Gavi funding: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2021 Jul 1;9(7):e942-56. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00167-4

- Zhang P, Zhang J. Surveillance on other infectious diarrheal diseases in China, from 2014 to 2015. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2017;38(4):424-430. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.04.003.

- Tang BC, Sun JL, Gao F, Wang LP, Zheng YM, Li ZJ. Epidemiological characteristics and genotype trends of rotavirus diarrhea in China from 2009 to 2020. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2024;45(4):506-512. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20231123-00312

- Li J, Wang H, Li D, Zhang Q, Liu N. Infection status and circulating strains of rotaviruses in Chinese children younger than 5-years old from 2011 to 2018: systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2021 Jun 3;17(6):1811-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1849519

- Luo HM, Ran L, Meng L, Lian YY, Wang LP. Analysis of epidemiological characteristics of report cases of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 5 years old in China, 2005-2018. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;54(2):181-186. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2020.02.013

- Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, Faruque AS. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The lancet. 2013 Jul 20;382(9888):209-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Final statistical monitoring report of the “National Program of Action for Child Development in China (2011–2020)” . December 2021. Available from: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-12/21/content_5663694.htm

- National Center for Chronic and Noncommunicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Statistical Information Center, National Health Commission. China cause-of-death surveillance dataset 2021. Available from: https://ncncd.chinacdc.cn/xzzq_1/202101/W020230317353700905354.pdf

- Zhang J, Duan Z, Payne DC, Yen C, Pan X, Chang Z, Liu N, Ye J, Ren X, Tate JE, Jiang B. Rotavirus-specific and overall diarrhea mortality in Chinese children younger than 5 years: 2003 to 2012. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2015 Oct 1;34(10):e233-7. DOI: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000799

- Ren JH, Wang R. Epidemiological characteristics of public health emergencies caused by other infectious diarrhea in China from 2017 to 2021. Journal of Tropical Diseases and Parasitology. 2023;21(1):1-6. DOI:http://www.rdbzz.com/CN/10.3969/j.issn.1672-2302.2023.01.001

- Yee EL, Fang ZY, Liu N, Hadler SC, Liang X, Wang H, Zhu X, Jiang B, Parashar U, Widdowson MA, Glass RI. Importance and challenges of accurately counting rotavirus deaths in China, 2002. Vaccine. 2009 Nov 20;27:F46-9. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.065

- Li F, Guo L, Li Q, Xu H, Fu Y, Huang L, Feng G, Liu G, Chen X, Xie Z. Changes in the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of viral gastroenteritis among hospitalized children in the Mainland of China: a retrospective study from 2016 to 2020. BMC pediatrics. 2024 May 4;24(1):303. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04776-1

- Wei YH, Li JX, Peng R, Wang MX, Sun XM, Zhang Q, Wang H, Fan JX, Li DD, Duan ZJ. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of hospitalized children with G9P[8] group A rotavirus diarrhea in China from 2011 to 2019. Disease Surveillance. 2022;37(6):760-763. DOI:10.3784/jbjc.202111110589

- Wang MW, Li JX, Gao SH, Sun XM, Zhang Q, Wang H, Li DD, Duan ZJ. Epidemiological characteristics of group A rotavirus infection in hospitalized children under 5 years of age with diarrhea in China in 2019. Chinese Journal of Experimental and Clinical Virology. 2022;36(2):172-175. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112866-20211230-00217

- Lou JT, Xu XJ, Wu YD, Tao R, Tong MQ. Epidemiology and burden of rotavirus infection among children in Hangzhou, China. Journal of clinical virology. 2011 Jan 1;50(1):84-7. DOI:10.1016/j.jcv.2010.10.003

- Jin H, Wang B, Fang Z, Duan Z, Gao Q, Liu N, Zhang L, Qian Y, Gong S, Zhu Q, Shen X. Hospital-based study of the economic burden associated with rotavirus diarrhea in eastern China. Vaccine. 2011 Oct 13;29(44):7801-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.104、

- Kawai K, O’Brien MA, Goveia MG, Mast TC, El Khoury AC. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis and distribution of rotavirus strains in Asia: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012 Feb 8;30(7):1244-54. DOI: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.092.

- Meng XQ. Study on direct economic burden of rotavirus diarrhea and direct economic benefit of vaccination [dissertation]. Shandong, China: Shandong University; 2023.

- Fu XL, Ma Y, Li Z, Qi YY, Wang SJ, Fu LJ, Wang SM, von Seidlein L, Wang XY. Cost-of-illness of gastroenteritis caused by rotavirus in Chinese children less than 5 years. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2023 Dec 15;19(3):2276619. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2276619