直接效果

降低发病率

现有监测数据表明,在接种PCV13后,儿童中血清型3型侵袭性肺炎球菌病 (IPD)的发病率降低。例如,美国在引入PCV13之后,5岁以下儿童中的血清型IPD发病率从2010年的1.1例/10万下降到2013年的0.25例/10万1;英国在引入PCV13后,5岁以下儿童中血清型3型IPD病例的数量也有所下降,2013-2014年报告发病率比2008年下降了68% (95% CI: 6%-89%)2。另一项研究通过比较 PCV13 引入前(2008/09-2009/10 年)和 PCV7 引入前(2000/01-2005/06 年)的发病率比率基线,评估 PCV 疫苗引入英格兰和威尔士后对人群的影响。 到 2016/17 年,所有年龄组的 PCV7 型侵袭性肺炎球菌疾病发病率与 PCV7 引入前相比下降了 97%,而 PCV13 型侵袭性肺炎球菌疾病自 PCV13 引入以来则下降了 64%3。2016年蒙古将PCV13疫苗逐步纳入婴儿常规免疫计划后,2-59个月儿童肺炎发病率显著降低,PCV13型携带率总体下降了44%4。

美国是全球第一个将PCV疫苗纳入国家免疫规划的国家(2000年引入PCV7)。2021年发表的一项模型研究旨在量化美国在纳入PCV7及PCV13疫苗20年以来PCV与IPD发病率的关系。结果显示,PCV疫苗避免了至少28.2万例IPD病例,其中包括约1.6万例脑膜炎,约17.2万例菌血症和约5.5万例细菌性肺炎。此外,接种PCV疫苗预防了9700万人次因中耳炎就诊,438,914至706,345人次因肺炎住院以及2,780例死亡。IPD病例由1997年的15,707例下降至2019年的1,382例,下降了91%。中耳炎的年均就诊次数从PCV 13引入前的78人次/100名儿童下降到PCV 13引入后的46人次/100名儿童,下降了41%。肺炎年住院人数从1997年的11万至17.5万例下降至2019年的3.7万例,下降了66%-79%。研究结果证实了接种PCV疫苗对预防儿童IPD具有显著益处5。2019年发表的一项关于非洲地区的PCV10/PCV13对5岁以下儿童IPD有效性的系统综述显示,引入PCV后,IPD的总体下降幅度在31.7% 至80.1% 之间。由疫苗覆盖的血清型引起的IPD明显下降,下降范围为35.0% 至92.0%。在24个月以下的儿童中下降幅度更大(55.0%至89.0%)。在所有疫苗血清型中,血清型1、5和19A的相对比例在疫苗推广后增加了一倍6。

接种程序所致效果差异

在已将PCV纳入国家免疫规划的高收入国家中,3剂次接种程序可以为儿童提供显著保护,使用的接种程序最终取决于实施时的环境7。3剂次基础免疫程序可以在儿童出生后的第一年,即其疾病风险最高时,提供良好的保护。包含一个加强针的程序(例如,3剂基础免疫+ 1剂加强针)可以提供更强的长期保护,特别是针对血清型18。

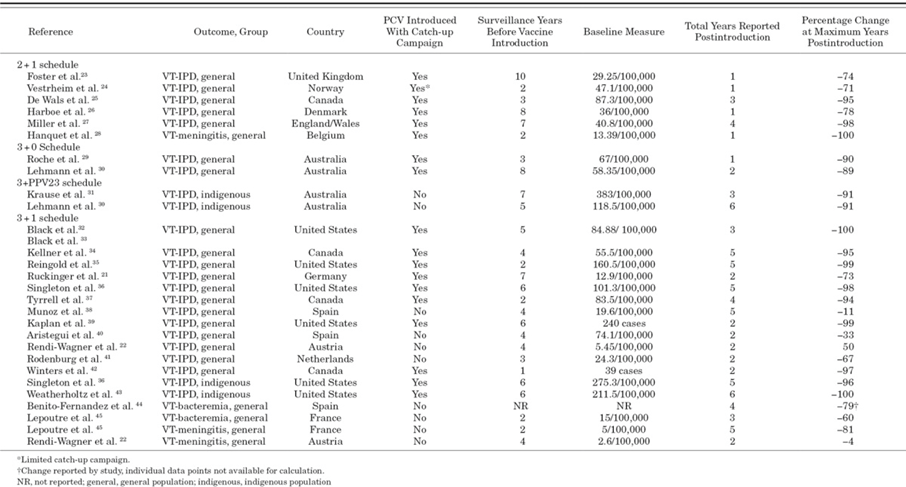

2013 年的一项系统性回顾比较了 PCV 疫苗不同免疫程序对幼儿疫苗型侵入性肺炎球菌疾病(VT-IPD)的影响。 该研究支持使用加强针。 研究显示,在纳入的临床试验中,3+0 接种方案的疫苗效力为 65% 至 71%,3+1 接种方案的效力为 83% 至 94%。 监测数据和病例数显示,2+1 或 3+1 接种程序可使 VT-IPD 减少 100%,3+0 接种程序可减少 90%。 病例的减少最早可在 PCV 推出 1 年后观察到9。

表1 不同PCV接种程序下,PCV引入对幼儿疫苗血清型IPD(VT-IPD)、脑膜炎或菌血症的影响

间接影响

降低全人群疾病负担

大部分国家在引入PCV疫苗后,成年人的IPD和肺炎发病率有所下降。人群保护效果取决于PCV的接种率和 PCV引入并实施的时间,PCV引入的时间越长,疫苗的间接效应越明显。且只有在疫苗覆盖率高(70%-80%以上)的人群中才能实现较好的间接保护。因此,儿童接种疫苗对群体保护程度有重大影响7。

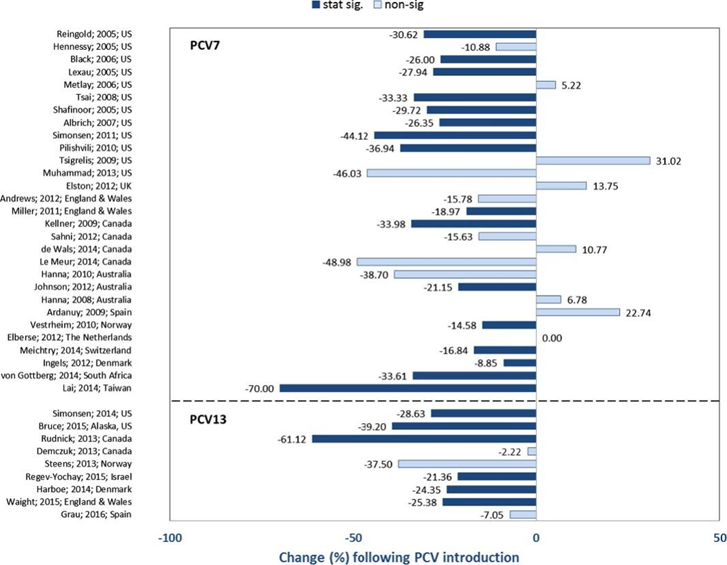

美国的监测数据显示,继PCV7引入后,成年人中IPD发病率出现统计学意义上的显著下降,或者没有显著变化,降低程度不相同,最高降幅为46.0%10。在大多数研究中,IPD发病率在65岁以上人群中降低最明显7。这一变化主要与PCV引入后的持续时间有关。在PCV7引入较晚的国家中,尽管总体上也显示出IPD发病率下降的趋势,但下降幅度存在较大的差异。例如PCV7实施三年后,2010年丹麦65岁以上人群发病率下降了8.8%11;PCV7实施七年后,2012年整个台湾地区成年人IPD发病率下降高达70.0%12。

多项研究表明,PCV10和/或PCV13的引入也减少了IPD发病率。但降低程度在不同地区存在差异。例如在加拿大安大略省,65岁以上成年人接种PCV7、PCV10和PCV13后,IPD发病率总体下降了多达61.12%13;而在以色列18岁以上人群中, PCV7和PCV13仅使IPD发病率总体下降了21.3%14。美国阿拉斯加15的一项研究显示,在引入PCV13后,18岁至44岁的成年人IPD发病率显著下降,但在45岁及以上人群中未见显著变化。

疾病负担降低时点预测

2017年一项研究对儿童接种PCV疫苗对全人群IPD的间接影响进行了系统综述与荟萃分析,共纳入242篇研究,结果显示,对儿童实施PCV疫苗接种方案,在十年内可以为全人群提供实质性的保护。在评估老年人疫苗接种计划时,应当考虑儿童疫苗接种的间接保护作用16。

在所有年龄组中,PCV7血清型引起的IPD发病率降低90%所需的平均时长为8.9年 (95%CI: 7.8-10.3年),对于PCV13新增的6个血清型,其发病率降低90%的预估平均时长为9.5年(6.1-16.6年)。随着时间推移,群体免疫效应将继续积累16。

表2 采取儿童PCV疫苗接种方案,未接种疫苗年龄组IPD发病率变化的模型估计和预测

| 相对危险度 RR(95% CI) | 降低50%计划年数 (95% CI)* | 降低90%计划年数 (95% CI)* | ||

| PCV7 血清型 | ||||

| 疫苗血清型 (全年龄组) | ||||

| 4 | 0.77 (0.72–0.84) | 2.8 (2.0–3.8) | 9.1 (7.1–12.2) | |

| 6B | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) | 2.7 (1.9–3.6) | 9.7 (7.7–12.8) | |

| 9V | 0.70 (0.66–0.77) | 2.5 (2.0–3.1) | 7.1 (5.9–8.8) | |

| 14 | 0.76 (0.69–0.85) | 1.9 (0.9–3.2) | 8.0 (5.9–12.6) | |

| 18C | 0.79 (0.73–0.86) | 4.1 (3.3–5.8) | 11.1 (8.8–17.0) | |

| 19F | 0.84 (0.80–0.90) | 5.1 (4.1–7.0) | 14.7 (11.8–22.2) | |

| 23F | 0.73 (0.68–0.79) | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 8.0 (6.6–10.0) | |

| 交叉反应血清型 (全年龄组) | ||||

| 6A | 0.84 (0.78–0.89) | 6.4 (5.0–9.3) | 15.4 (11.8–23.1) | |

| 9N | 1.03 (0.95–1.13) | .. | .. | |

| 19A | 0.97 (0.84–1.15) | .. | .. | |

| 全年龄组 (所有PCV7血清型) | ||||

| 全年龄 | 0.79 (0.75–0.81) | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | 8.9 (7.8–10.3) | |

| <5岁 | 0.62 (0.55–0.70) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 4.6 (3.9–6.0) | |

| 5–18岁 | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 3.1 (1.9–4.9) | 10.8 (7.5–21.1) | |

| 19–49岁 | 0.85 (0.76–0.96) | 1.9 (0.0–3.8) | 11.9 (8.0–30.0) | |

| 50–64岁 | 0.78 (0.73–0.85) | 2.7 (2.0–3.4) | 9.1 (7.5–12.2) | |

| ≥65岁 | 0.77 (0.75–0.80) | 2.6 (2.3–3.0) | 8.9 (7.9–10.3) | |

| 增加PCV13血清型 | ||||

| 疫苗血清型 (全年龄组) | ||||

| 6A | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | 0.4 (0.0–30.0) | 11.9 (4.8–30.0) | |

| 1 | 0.76 (0.57–1.04) | 2.2 (0.6–30.0) | 7.8 (4.2–30.0) | |

| 3 | 1.03 (0.88–1.22) | 30.0 (6.8–30.0) | 30.0 (20.9–30.0) | |

| 5 | 0.59 (0.04–3.06) | 0.1 (0.0–30.0) | 5.7 (0.0–30.0) | |

| 7F | 0.83 (0.67–1.01) | 5.4 (2.9–30.0) | 14.1 (7.1–30.0) | |

| 19A | 0.74 (0.54–0.92) | 2.9 (2.0–10.5) | 7.6 (4.7–28.4) | |

| 全年龄组(增加PCV13血清型) | ||||

| 全年龄组 | 0.75 (0.64–0.87) | 3.6 (2.5–6.1) | 9.5 (6.1–16.6) | |

| <5岁 | 0.93 (0.30–2.64) | 0.0 (0.0–30.0) | 13.8 (0.0–30.0) | |

| 5–18岁 | 0.78 (0.55–1.08) | 3.0 (0.0–30.0) | 9.5 (4.7–30.0) | |

| 19–49岁 | 0.74 (0.56–0.99) | 3.1 (1.5–30.0) | 8.5 (4.6–30.0) | |

| 50–64岁 | 0.77 (0.59–0.99) | 4.3 (2.4–30.0) | 10.4 (5.6–30.0) | |

| ≥65岁 | 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | 4.1 (2.6–7.4) | 10.3 (6.4–20.7) | |

| IPD | ||||

| 全年龄组(IPD) | ||||

| 全年龄组 | 0.99 (0.96–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| <5岁 | 0.97 (0.91–1.01) | .. | .. | |

| 5–18岁 | 0.97 (0.92–1.01) | .. | .. | |

| 19–49岁 | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| 50–64岁 | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| ≥65岁 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| ..:代表未估计 *:最高上限为30年,超过30年代表永远不会达到减少50%或90%的程度。 | ||||

审核校对:李周蓉 郭磊 张馨予

文献整理:张翯昱

网页编辑:祖嘉琦

参考文献

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Invasive pneumococcal disease in the U.S., 2008–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/pneumo-04-matanock.pdf

- Waight PA, Andrews NJ, Ladhani SN, Sheppard CL, Slack MP, Miller E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:535–43.

- Ladhani SN, Collins S, Djennad A, et al. Rapid increase in non-vaccine serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales, 2000-17: a prospective national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Apr;18(4):441-451. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30052-5. Epub 2018 Jan 26. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Apr;18(4):376. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30074-4.

- Wasserman M, Chapman R, Lapidot R, et al. Twenty-Year Public Health Impact of 7- and 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines in US Children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(6):1627-1636.

- Ngocho JS, Magoma B, Olomi GA, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines against invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five years of age in Africa: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019 Feb 19;14(2): e0212295.

- Tsaban G, Ben-Shimol S. Indirect (herd) protection, following pneumococcal conjugated vaccines introduction: A systematic review of the literature. Vaccine. 2017 May 19;35(22):2882-2891.

- Klugman KP, Madhi SA, Adegbola RA, et al. Timing of serotype 1 pneumococcal disease suggests the need for evaluation of a booster dose. Vaccine. 2011;29:3372–3373.

- Muhammad RD, Oza-Frank R, Zell et al. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among high-risk adults since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for children. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Mar;56(5):e59-67. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis971.

- Hennessy TW, Singleton RJ, Bulkow LR, et al. Impact of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive disease, antimicrobial resistance and colonization in Alaska Natives: progress towards elimination of a health disparity. Vaccine. 2005 Dec 1;23(48-49):5464-73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.100.

- Lai CC, Lin SH, Liao CH, et al. Decline in the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease at a medical center in Taiwan, 2000-2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Feb 11;14:76. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-76.

- von Mollendorf C, Ulziibayar M, Nguyen CD, Batsaikhan P, Suuri B, Luvsantseren D, Narangerel D, de Campo J, de Campo M, Tsolmon B, Demberelsuren S, Dunne EM, Satzke C, Mungun T, Mulholland EK. Effect of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine on Pneumonia Incidence Rates among Children 2-59 Months of Age, Mongolia, 2015-2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024 Mar;30(3):490-498. doi: 10.3201/eid3003.230864.

- Rudnick W, Liu Z, Shigayeva A, et al. Pneumococcal vaccination programs and the burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in Ontario, Canada, 1995-2011. Vaccine. 2013 Dec 2;31(49):5863-71. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.049.

- Regev-Yochay G, Paran Y, Bishara J, et al. Early impact of PCV7/PCV13 sequential introduction to the national pediatric immunization plan, on adult invasive pneumococcal disease: A nationwide surveillance study. Vaccine. 2015 Feb 25;33(9):1135-42. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.030.

- Bruce MG, Singleton R, Bulkow L, et al. Impact of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (pcv13) on invasive pneumococcal disease and carriage in Alaska. Vaccine. 2015 11;33(38):4813-9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.080.

- Shiri T, Datta S, Madan J, et al. Indirect effects of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 Jan;5(1):e51-e59.