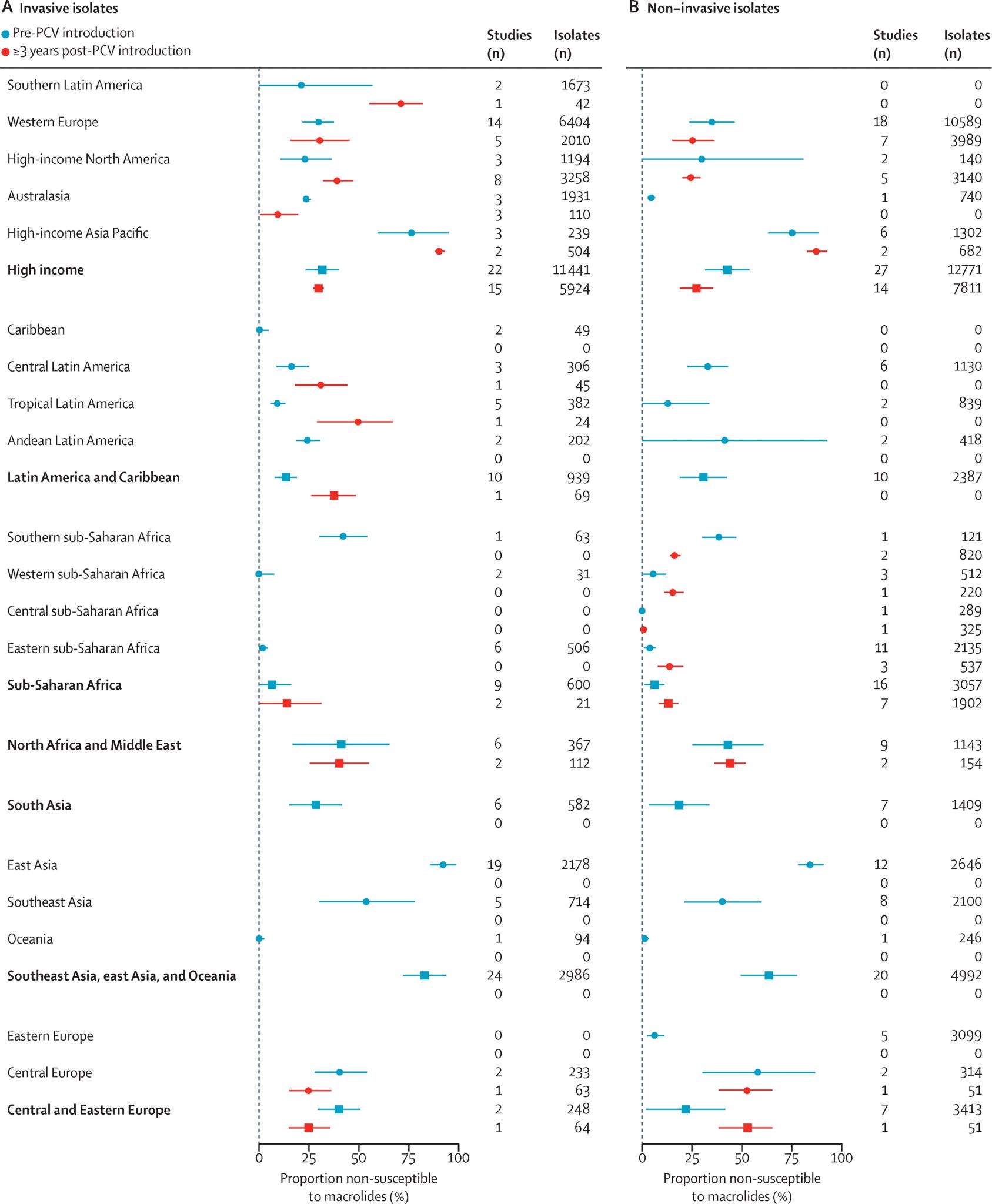

Introduction

Pneumococcal disease remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among children worldwide. Based on cumulative evidence and surveillance data, Streptococcus pneumoniae has consistently been identified as a major infectious cause of death and one of the main drivers of antibiotic use in children under five years of age globally.1 Randomized controlled trials and post-marketing observational studies have demonstrated that large-scale implementation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) substantially reduces antibiotic consumption and decreases resistance among vaccine-type pneumococcal strains.

Global Evidence

Impact of PCV on Antibiotic Use

Vaccines can reduce the burden of antimicrobial resistance in part by preventing infections that would otherwise require antibiotic treatment. Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) and diarrhea are the predominant reasons for antibiotic use among children in low-income countries. In these settings, diagnostic tools to guide appropriate treatment are limited, leading clinicians to rely on empirical antibiotic therapy based on suspected cases rather than confirmed etiologic diagnosis.2

A multi-country analysis estimated the incidence of antibiotic-treated ARIs among children aged 24–59 months in low-income countries. Annual ARIs incidence ranged from 89.5 to 194.8 episodes per 100 children, and the proportion of those receiving antibiotics ranged from 30.0% to 69.4%. In a case-control analysis including 18 low- and middle-income countries, children who received ≥ 3 doses of PCV10/13 had an 8.7% lower likelihood of receiving antibiotic treatment for ARIs compared with unvaccinated children.2

Based on the 2018 global coverage of PCVs (66.8%), researchers estimated that PCV10/13 immunization directly prevents approximately 23.8 million (95% CI: 4.2–52.0 million) antibiotic-treated ARI episodes annually among children aged 24–59 months in low-income settings. Expanding PCV10/13 coverage to all children in this age group could avert an additional 21.7 million (95% CI: 3.8–47.5 million) antibiotic-treated ARI episodes annually.3

For S. pneumoniae-associated acute otitis media (AOM) in children, a systematic review reported that following the introduction of PCVs—especially PCV13—into national immunization programs, the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pneumococcal strains declined markedly. Although serotype replacement remains a challenge, the overall burden of antibiotic resistance and AOM decreased, underscoring the substantial public health benefits of PCVs. The vaccines effectively reduce both AOM incidence and the circulation of resistant pneumococcal strains, thereby decreasing the need for broad-spectrum antibiotics and supporting antimicrobial stewardship.4

Pneumococcal Resistance Before and After PCV Introduction

Prior to the introduction of PCVs, surveillance studies on S. pneumoniae carriage and invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) indicated that vaccine-type (VT) pneumococci tended to exhibit reduced susceptibility or higher resistance to commonly used antibiotics compared with non-vaccine-type (NVT) strains. Evidence from a pre-licensure randomized controlled trial conducted in South Africa and two post-market case-control studies in the United States demonstrated that children vaccinated with PCVs had a significantly lower risk of developing antibiotic-resistant IPD than unvaccinated peers.5Long-term surveillance studies-mostly from high-income countries—further showed an increasing proportion of NVT pneumococcal isolates with reduced susceptibility or resistance to penicillin and macrolides following PCV introduction.6,7,8

A 2021 systematic review and meta-regression described temporal changes in antimicrobial susceptibility among pneumococcal isolates from children with nasopharyngeal carriage and IPD. The study found that following PCV implementation, S. pneumoniae isolates exhibited reduced non-susceptibility and resistance to penicillin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and third-generation cephalosporins, as well as a decline in tetracycline resistance. However, no consistent change was observed in the prevalence of macrolide non-susceptibility before versus after PCV introduction.3

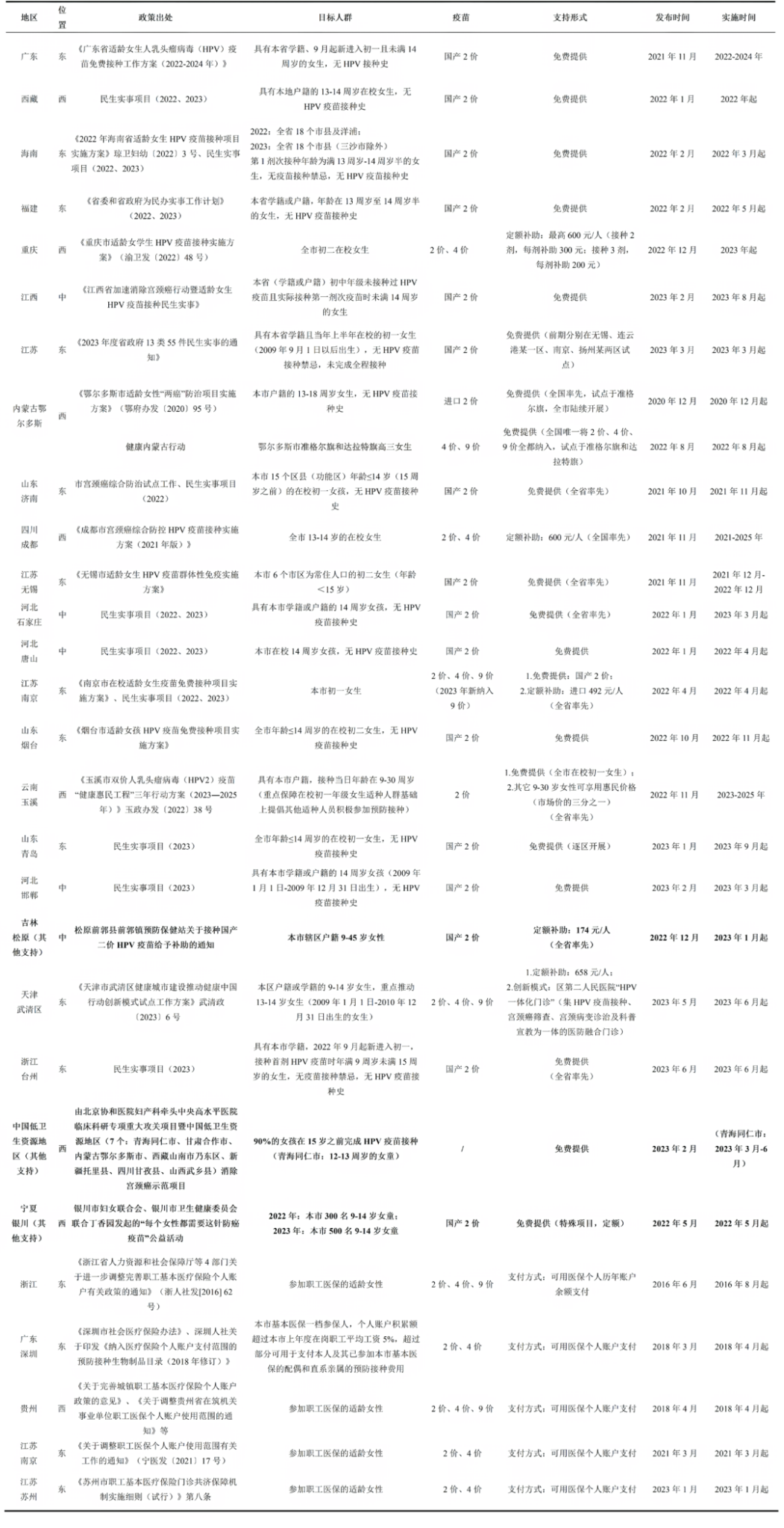

Figure 1. Prevalence of non-susceptibility to penicillin in invasive and non-invasive S. pneumoniae isolates, before and after PCV introduction, by Global Burden of Disease regions and super-region3

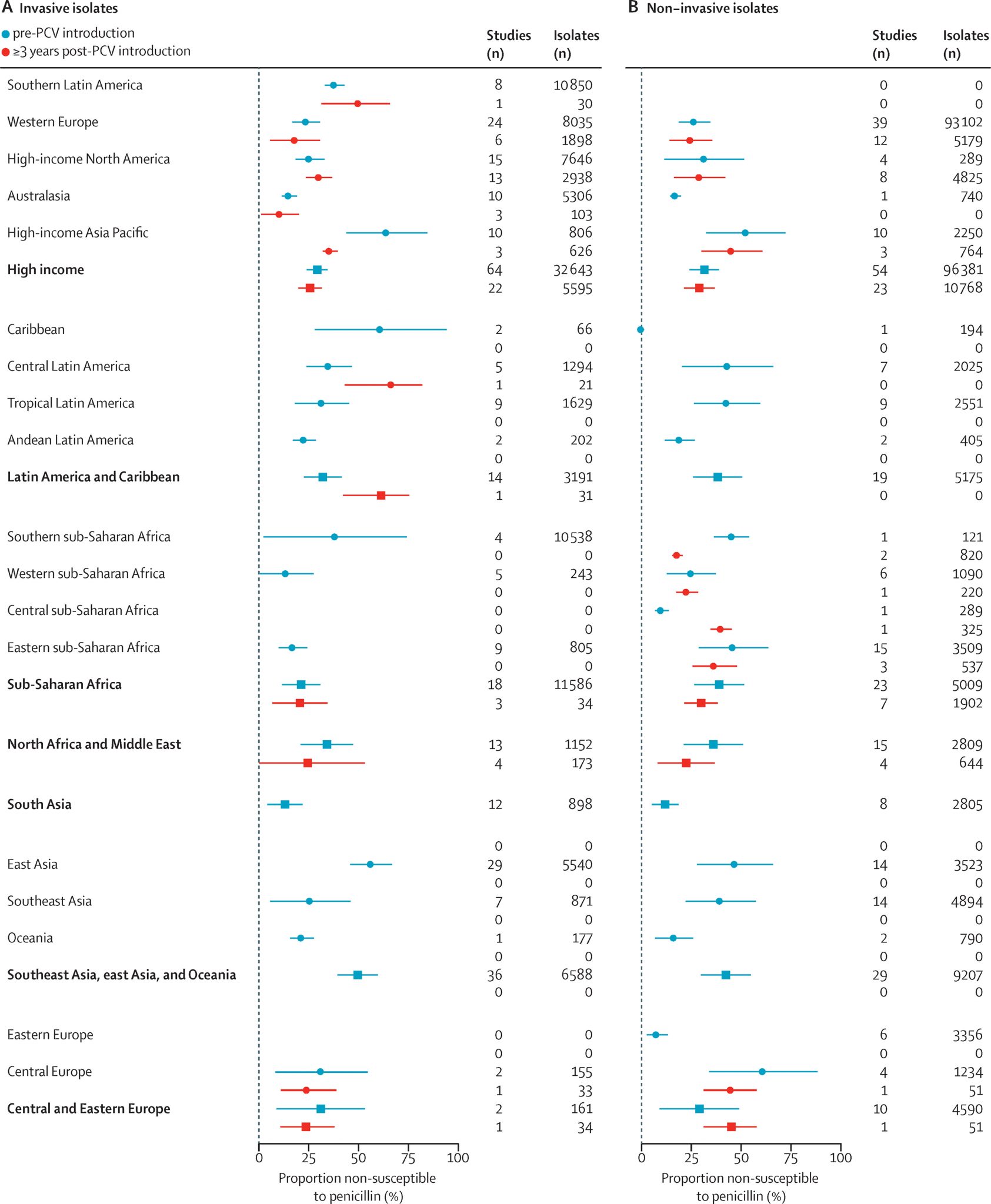

Figure 2. Prevalence of non-susceptibility to macrolide in invasive and non-invasive S. pneumoniae isolates, before and after PCV implementation, by Global Burden of Disease regions and super-region3

The review also estimated that at the time of PCV introduction, the absolute prevalence of penicillin-resistant strains was 7.6% higher (95% CI: 4.5–10.8) among VT isolates than among NVT. Similarly, the prevalence of macrolide-resistant strains was 11.5% higher (95% CI: 6.7–16.4) in VT isolates. Although resistance decreased among both VT and NVT strains over time, the decline was significantly greater in VT strains. For macrolides, however, the analysis did not detect any significant post-PCV change in the prevalence of non-susceptibility among either VT or NVT strains.3

The Situation in China

Regarding overall S. pneumoniae resistance, antimicrobial resistance among pediatric isolates in China has intensified, with high rates of cross-resistance and multidrug resistance (MDR) to commonly used antibiotics.9 A 2024 study conducted at a pediatric hospital in Beijing reported that from 2015 to 2022, the resistance rate of S. pneumoniae (non-meningitis isolates) to penicillin declined from 6.5% to 0.6%, and resistance to cefotaxime, cefepime, and meropenem also showed decreasing trends. However, resistance to tetracycline, clindamycin, and erythromycin remained high.10 Another study analyzing S. pneumoniae isolates from Guangzhou (2012–2020) found a year-on-year increase in multidrug-resistant strains, with rising resistance to meropenem and cefotaxime, while penicillin resistance declined.11

Study in China specifically assessing the impact of PCV introduction on pneumococcal resistance remains limited. PCV7 was introduced in 2008, followed by PCV13 in 2016, which replaced PCV7 in the market. However, as PCVs are non–National Immunization Program (non-NIP) vaccines in China, vaccination requires out-of-pocket payment, resulting in persistently low coverage.12 A systematic review of studies published between 2017 and 2024 on pneumococcal serotypes isolated from children <14 years of age across mainland China found that both serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance patterns remained relatively stable following the introduction of PCV13 became available as a private vaccine. The highest rate of antimicrobial resistance was observed for erythromycin (93.73%; 95% CI: 90.58–96.88), followed by azithromycin, tetracycline, clindamycin, and sulfamethoxazole. Regional variation in serotype prevalence and vaccine coverage was notable across provinces and strain types.12

A 2025 study conducted in Hainan Province evaluated S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal carriage and antimicrobial resistance among children under five in regions with differing PCV13 coverage levels. The investigation included Haikou (high-coverage area) and Wanning, Baisha, and Qiongzhong (low-coverage areas).

Results indicated that vaccinated children had significantly lower carriage of vaccine-type (VT) serotypes—including 6B (7.0% vs. 2.7%, P < 0.01), 6A (4.2% vs. 1.2%, P < 0.05), and 23F (2.2% vs. 0.3%, P < 0.05)—compared with unvaccinated children. In high-coverage regions, pneumococcal isolates showed lower non-susceptibility to penicillin, cefuroxime, erythromycin, azithromycin, clindamycin, and sulfamethoxazole, as well as a significantly lower proportion of multidrug-resistant strains, compared with low-coverage regions.

Content Editor: Tianyi Deng, Ziqi Liu

Page Editor: Ziqi Liu

References

1. Walker, C. L. F., Rudan, I., Liu, L., Nair, H., Theodoratou, E., Bhutta, Z. A., O’Brien, K. L., Campbell, H., & Black, R. E. (2013). Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet (London, England), 381(9875), 1405–1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6

2. Lewnard, J. A., Lo, N. C., Arinaminpathy, N., Frost, I., & Laxminarayan, R. (2020). Childhood vaccines and antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries. Nature, 581(7806), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2238-4

3. Andrejko, Kristin, et al. “Antimicrobial resistance in paediatric Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates amid global implementation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis.” The Lancet Microbe 2.9 (2021): e450-e460.

4. Dissanayake, G., Zergaw, M., Elgendy, M., Billey, A., Saleem, A., Zeeshan, B., … & Zergaw, M. F. (2024). Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines Over Antibiotic-Resistant Acute Otitis Media in Children: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 16(8).

5. Dagan, R., & Klugman, K. P. (2008). Impact of conjugate pneumococcal vaccines on antibiotic resistance. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 8(12), 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70281-0

6. Huang, Susan S., et al. “Continued impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on carriage in young children.” Pediatrics 124.1 (2009): e1-e11.

7. Fenoll, A., et al. “Temporal trends of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes and antimicrobial resistance patterns in Spain from 1979 to 2007.” Journal of clinical microbiology 47.4 (2009): 1012-1020.

8. Van Effelterre, Thierry, et al. “A dynamic model of pneumococcal infection in the United States: implications for prevention through vaccination.” Vaccine 28.21 (2010): 3650-3660.

9. Expert Consensus on Immunization for Pneumococcal Diseases (2020 Edition). Chinese Journal of Vaccines and Immunization. 2021;27(1):1–47. doi:10.19914/j.CJVI.2021001.

10. Lü G, Dong F, Lü ZY. Clinical distribution and antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in a pediatric hospital in Beijing. Laboratory Medicine. 2024;39(11):1122–1127.

11. Lü JW, Tian BS, Yin XC, Zhao YH, Liu SL, Yang JY, Zhang J, Xiao YJ, Gu B. Increasing trends of Streptococcus pneumoniae antimicrobial resistance and clustering patterns of multidrug resistance in Guangzhou, 2012–2020. Journal of Nanjing Medical University (Natural Science Edition). 2022;42(6):854–860.

12. Li Y, Wang S, Hong L, Xin L, Wang F, Zhou Y. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in China among children under 14 years of age post-implementation of the PCV13: a systematic review and meta-analysis (2017-2024). Pneumonia (Nathan). 2024;16(1):18. Published 2024 Oct 5. doi:10.1186/s41479-024-00141-z

13. Wang, Jian, et al. “Different patterns of antimicrobial non-susceptibility of the nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in areas with high and low levels of PCV13 coverage.” Vaccine 62 (2025): 127455.