Following the end of the war in 1994, the Rwandan government prioritized healthcare as a key focus for national reconstruction. As a low-income country in East Africa, Rwanda has long faced a significant burden of cervical cancer, which ranks as a leading cause of female cancer and death. Before 2011, the age-standardized incidence rate of cervical cancer was 34.5 cases per 100,000 women, with an age-standardized mortality rate of 25.4%[1]. Due to weak health infrastructure, most patients were diagnosed at an advanced stage of cervical cancer. To address this public health challenge, the Rwandan government designated cervical cancer a health priority in 2008 and formally launched the National HPV Vaccination Program in 2011, becoming the first low- and middle-income country in Africa to implement such an initiative.

Public-Private Partnerships Facilitates National Cervical Cancer Prevention Strategy

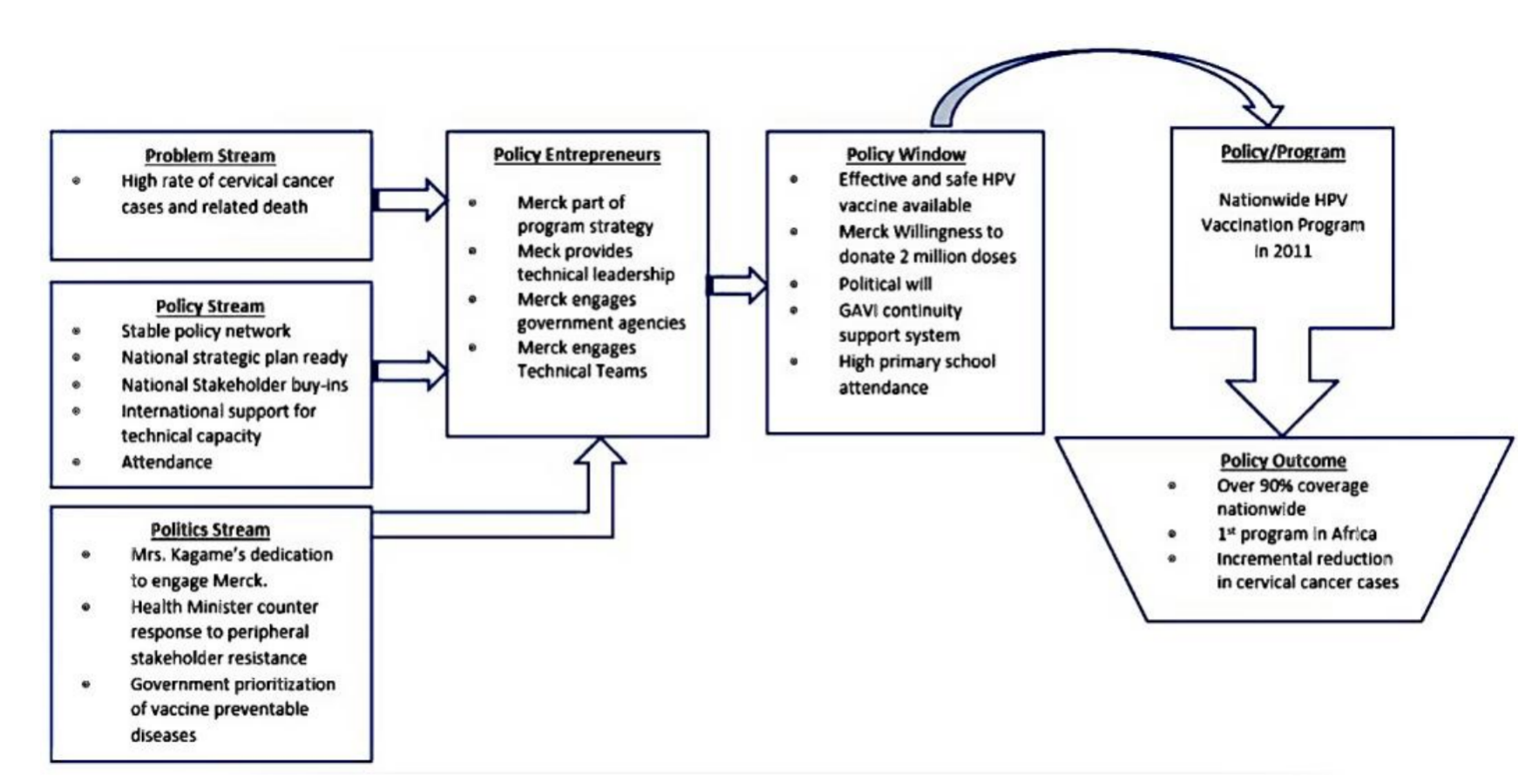

In April 2009, Rwanda’s First Lady met with senior executives from Merck to initiate advocacy for the HPV vaccine on behalf of women in Rwanda. An internal technical discussion then occurred between Merck and the Ministry of Health, followed by conversations with development partners in Rwanda’s health sector. Under the Ministry’s leadership, Merck also contributed to developing the National Strategic Plan for the Prevention, Control, and Management of Cervical Lesions and Cancer. This plan included a vaccination program (3-dose schedule) for school-aged girls and routine cervical screening for women aged 35 to 45[1].

A memorandum of understanding signed in December 2010 guaranteed Rwanda three years of vaccinations at no cost and concessional prices for future doses[2]. As the Rwandan government lacked sufficient financial resources to independently fund the program, agreements were established with Qiagen (a provider of HPV testing products) and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi) to ensure the sustainability and continuity of Rwanda’s cervical cancer elimination efforts. Following the conclusion of the three-year collaboration with Merck, Gavi agreed to cover the cost of the vaccines supplied by Merck[1], supporting Rwanda’s HPV program through a co-financing model. Under this arrangement, Rwanda pays $0.20 per vaccine dose, with Gavi covering the remainder[1].

Flowchart of Kingdon’s MSF framework used to clarify the HPV vaccination policymaking process in Rwanda[1].

The Health Sector Drives Vaccination Implementation

Driven by the principles of equity, value and quality, Rwanda’s health sector has demonstrated significant progress in recent years. The Rwandan government enshrined a commitment to prioritize health as a human right in its constitution (Article 41), stating that “All citizens have rights and duties relating to health”. The State is responsible for mobilizing activities aimed at promoting good health and assists in implementing them [1, 2].

On 26 and 27 April 2011, 93,888 Rwandan girls in primary school grade six received their first dose of the HPV vaccine free of charge. Data indicates that the coverage rate for the full three-dose HPV vaccination series reached 93.23%[2]. Three strategic decisions were critical to Rwanda’s successful HPV vaccine rollout[2]:

First, in September 2010, the Ministry of Health expanded its Vaccination Technical Working Group to include representatives from the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, the National Center for Research and Control of AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and Other Epidemics, and healthcare workers involved in cancer care. This technical working group was tasked with defining cold chain requirements, determining the number of school-going and out-of-school girls, designing tools for nurse and community health worker capacity training, and supervising the procurement and distribution logistics, implementation budgets, education and advocacy, data collection, and social mobilization. In the months preceding vaccination implementation, the government also spearheaded a nationwide awareness campaign. The First Lady delivered a mobilization speech, and healthcare professionals, local government officials, clergy, and others educated parents and children about the new vaccine.

Second, since 98% of Rwandan girls attend primary school, the Ministry of Health collaborated with the Ministry of Education to design a school-based implementation strategy for delivering the standard three-dose HPV vaccine schedule to achieve maximum coverage. To ensure eligible girls did not miss vaccination opportunities, Rwanda mobilized 45,000 community health workers to actively track girls enrolled in sixth grade who were absent on vaccination days, as well as a small number of girls aged 12 who were not enrolled in school. After confirmation by community health workers, both groups received vaccinations at local health centers.

Third, the technical working group decided on a multi-phased vaccination strategy spanning three years. Every year beginning in 2011, girls enrolled in primary grade six will receive the full three-dose course of HPV vaccine. During the programme’s second and third years, a “catch-up” phase targeting girls in the third year of secondary school will ensure complete coverage of all pre-adolescent and adolescent girls. In 2014 and beyond, only primary grade six vaccinations will be necessary.

Challenges and Resistance

During the initial phase of vaccine rollout, one of the greatest challenges for implementers was communicating eligibility criteria for HPV vaccination to residents nationwide. Some parents requested vaccination for all their children, and some female teachers also sought access. Through radio broadcasts and in-person outreach, Ministry of Health representatives acknowledged the potential benefits of vaccinating all women at high risk for cervical cancer but clarified that the national program targeted only girls before their first sexual encounter.

Although Rwanda’s policy environment remained stable throughout the HPV vaccine decision-making process, stakeholder resistance persisted. Academics wrote to The Lancet expressing “serious doubts about whether this arrangement [Rwanda’s partnership with Merck] serves the best interests of the people.” Rwanda’s Minister of Health and colleagues responded to these arguments in a letter to The Lancet editors, highlighting the stable public discourse and policy environment supporting HPV vaccine implementation[1].

Additionally, concerns about the high cost of the new vaccine led some to argue that prioritizing cervical cancer prevention might divert scarce resources from other more “cost-effective” childhood health interventions. However, Rwanda government and Merck addressed challenges in health budget allocation and difficult decision-making by signing an agreement guaranteeing free HPV vaccines for the program’s first three years.

Program Outcomes and Implications

Through innovative partnerships, Rwanda narrowed the two-decade gap in vaccination coverage between high- and low-income countries to just five years. Between 2011 and 2018, 1,156,863 girls received their first HPV vaccine dose, reaching 98% of the eligible target population; population coverage among girls born between 2001 and 2006 (aged 12) increased from 80% to 90%[3]. Rwanda’s HPV vaccine rollout success was not accidental; it stemmed from robust coordination, national ownership, strategic planning, comprehensive monitoring (particularly training school teachers to report side effects and adverse reactions), and strong administrative capacity. Key lessons for other low- and middle-income countries include:

First, comprehensive planning, coordination, and political commitment. Rwanda leveraged limited existing resources to effectively implement the HPV vaccination program, including dedicated community health workers, diverse communication channels for vaccine outreach, advocacy from women’s rights groups and NGOs, and support from the First Lady of Rwanda. Research indicates that high-level government backing and strong political will were also critical factors in achieving 95% coverage within three years[4].

Second, effective internal and external partnerships drive success. The driving force behind public-private partnerships lies in leveraging diverse efforts to create shared value. Donating vaccines to Rwanda and other low-income countries and communities aligns with Merck’s interests, as this initiative not only fulfills corporate social responsibility but also serves as a marketing strategy. It provides a social operating license and channels for selling medicines to low-income countries and communities at reasonable costs and terms[1]. Following the conclusion of the three-year donation period, Rwanda engaged Gavi to cover vaccine-related procurement costs as a continuity package for program advancement. However, the program’s success also demonstrates that vaccine manufacturers’ involvement in vaccine policy decision-making processes influences policy outcomes. Furthermore, senior ministry of Health officials in Rwanda acknowledged that an emphasis on health systems strengthening by the government, the Gavi, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria was key to the success of HPV vaccine rollout in the country[2].

Content Editors: Ziyi Zhu

Page Editor: Rurong Li

References

[1] Asempah E., Wiktorowicz M.E. Understanding hpv vaccination policymaking in Rwanda: A case of health prioritization and public-private-partnership in a low-resource setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20(21).

[2] Binagwaho A., Wagner C.M., Gatera M., et al. Achieving high coverage in rwanda’s national human papillomavirus vaccination programme. Bull World Health Organ. 2012, 90(8): 623-628.

[3] Sayinzoga F., Umulisa M.C., Sibomana H., et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage in rwanda: A population-level analysis by birth cohort. Vaccine. 2020, 38(24): 4001-4005.

[4] Ezezika, O., Purwaha, M., Patel, H. et al. The Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Project in Rwanda: Lessons for Vaccine Implementation Effectiveness. Glob Implement Res Appl 2, 394–403 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43477-022-00068-x