Japan approved the first HPV vaccine for market release in 2009 and began offering public subsidies to encourage vaccination in 2010. By April 2013, the vaccine was officially incorporated into the national immunization program, providing free routine vaccination services for girls aged 12–16. Between April and June 2013, the HPV vaccination rate reached nearly 70%. However, the government’s inadequate communication and management of vaccine safety concerns led to the suspension of active recommendations for the HPV vaccine for nearly a decade, with the recommendation being reinstated in November 2021. Studies indicate that the government’s suspension of active recommendation led to severe public distrust in the vaccine, resulting in a significant decline in vaccination coverage and a sharp increase in infection rates for the high-risk HPV types 16/18. This article will review Japan’s experience and lessons learned in addressing the HPV vaccine safety crisis based on publicly available literature.

1. HPV Vaccine Included in Japan’s National Immunization Program

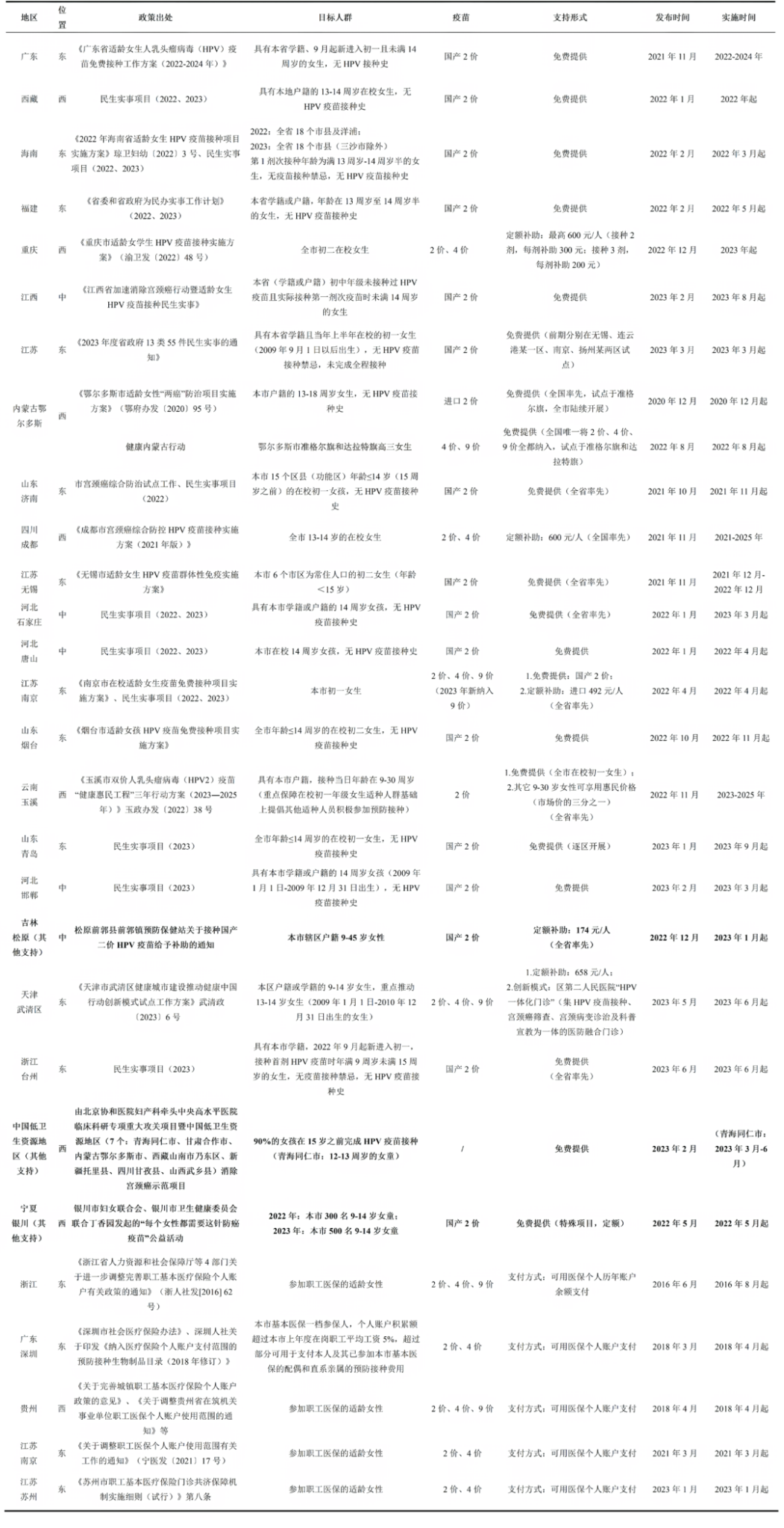

In Japan, the proportion of women undergoing cervical cancer screening is very low, yet the incidence of cervical cancer continues to rise. Therefore, the nationwide introduction of HPV vaccination is expected to help control cervical cancer. The bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix®) and the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil®) were launched in Japan in 2009 and 2011, respectively. Given the gap between Japan and other developed countries in terms of HPV vaccination rates, Japan launched an emergency HPV vaccination promotion project in 2010, funded by both the national and local governments, aimed at preventing cervical cancer. The project primarily targeted girls from first-year junior high school (13 years of age) to first-year high school (16 years of age). Initially, only the bivalent vaccine was used, with the quadrivalent HPV vaccine added in 2011. During the promotion program, the national HPV vaccination coverage rate in Japan increased from 70% to 80%. The Japanese government officially included the bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines into the National Immunization Program (NIP) in April 2013[1].

2. Policy Reversal Triggered by Safety Concerns

However, a few months before HPV vaccines were included in the NIP, high numbers of media reports of adverse events after the HPV vaccination were released. These reports included videos featuring girls with chronic pain, walking disturbances, involuntary movements, and other symptoms[1]. On June 14, 2013, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) announced the “suspension of active recommendations for HPV vaccines in the national immunization program” and stated that the suspension would continue until “sufficient safety information is obtained”[2]. Although the HPV vaccine was still available under the National Immunization Program, the government’s decision to suspend active recommendation exacerbated public concerns about vaccine safety, leading to a sharp decline in vaccination rates to less than 1% (for girls born in 2002 and later)[1,2].

Figure 1 HPV vaccination rates among girls born in different years in Japan[1]

Since 2013, the MHLW convened an Expert Committee on Adverse Reactions to Vaccines to collect data on suspected adverse cases reported by clinicians. However, the reported symptoms are wide-ranging and often lack clear clinical markers, suggesting a possible association with common psychosomatic imbalances during adolescence. Ongoing reviews have also failed to provide conclusive evidence of a direct causal relationship between HPV vaccines and chronic pain or nerve damage[3]. For example, a large-scale epidemiological study conducted in Nagoya in 2015 showed that the incidence rates of 24 symptoms, including pain and impaired motor function, reported in the unvaccinated group were not statistically different from those in the vaccinated group[4]. Another national survey found that adolescent females who had not received the HPV vaccine also experienced similar post-vaccination symptoms and sought medical attention[5].

In November 2018, a member of the House of Representatives submitted a written inquiry regarding the appropriateness of withholding recommendations for NIP vaccines against HPV infection. In response to this inquiry, the MHLW sent letters to all governors of every local government in both October 2020 and January 2021 to notify their residents that HPV vaccines are still included in the NIP, although the recommendation for proactive HPV vaccination had been suspended[1]. In November 2021, based on evidence supporting vaccine safety and in order to implement a new support system, the MHLW announced the resumption of active recommendations for HPV vaccination, which had been suspended for 8.5 years[3].

Thus, as part of the NIP, local authorities have resumed issuing HPV vaccination vouchers and reminder letters since April 2022. Nevertheless, according to a report based on precise figures from Fukui Prefecture, Japan, the coverage of HPV vaccines among target girls aged 16 years was reported to be approximately 30% in 2023. And the coverage rate for target women aged 17 to 25 years ranged from 12% to 65% (at least one dose). Women aged 23 years had the highest coverage rate at 65%, and this included women with previously incomplete HPV vaccination. Women aged 21 years had the lowest coverage rate at 12%[1].

3. The Japanese Government Introduced a series of Remedial Measures

After announcing the resumption of active recommendations for HPV vaccines, the MHLW initiated a 3-year catch-up free vaccination period from April 2022 to March 2025 for women born in f-year 1997 (17 years of age) to f-year 2005 (25 years of age). The target ages for catch-up free HPV vaccination corresponded to the age group that may have missed the opportunity to receive HPV vaccination because of the lack of information about it.

The MHLW also established a collaborative system to manage adverse events following HPV vaccination in order to promote nationwide HPV vaccination — medical facilities administering vaccinations in the community played a central role, with the MHLW designating affiliated hospitals and specialized facilities to manage severe pain. These measures facilitated effective collaboration between academic organizations, schools, and local governments, forming a robust support system. The Japanese Medical Association and the Japanese Society of Medical Science had also issued medical guidelines regarding symptoms that may occur after HPV vaccination[1,2].

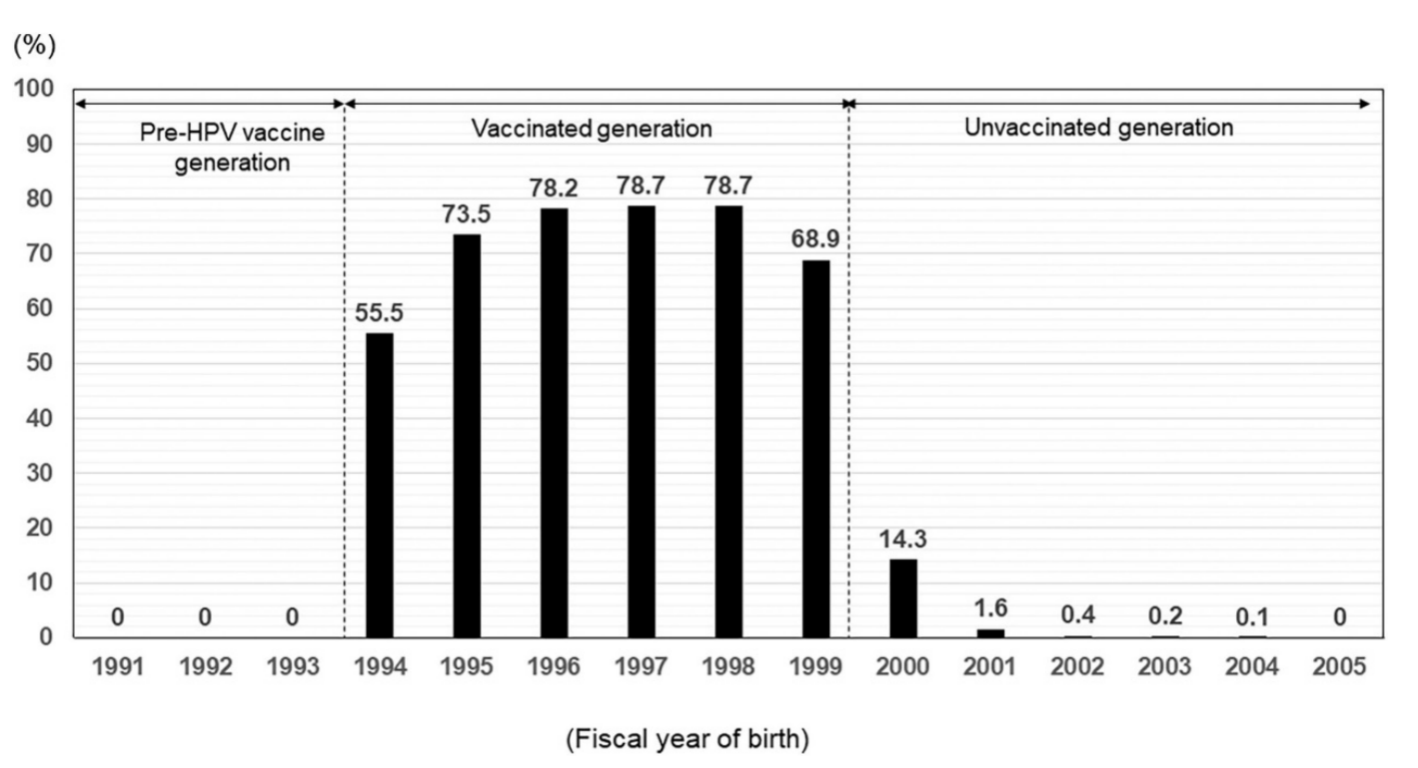

Despite a series of remedial measures, persistent information gaps, coupled with long-standing public skepticism, had hindered the rapid recovery of HPV vaccination rates, leaving many challenges unresolved. Research shows that the HPV 16/18 infection rate, which had declined due to increased HPV vaccination coverage, rose significantly again after the government suspended active recommendations, due to a decline in vaccination coverage[6]. A modeling study suggested that restoring HPV vaccine coverage to 70% in Japan could have prevented 14,800–16,200 cases and 3,000–3,400 deaths among girls born between 1994 and 2007[7].

Figure 2 Changes in HPV prevalence and HPV vaccination coverage among women aged 20-21 years who underwent cervical screening in Niigata City, Japan[6]

4 Lessons Learned from Mishandling the Vaccine Crisis

4.1 Imbalance in professional perspectives

The Vaccine Adverse Reaction Review Committee (VARRC) consists of experts including infectious disease experts, pediatricians, pharmacologists, members of the Executive Committee of the Japan Medical Association, and public health experts. However, it lacks representatives from obstetrics and gynecology clinical experts and patient advocacy groups. During the suspension period from 2013 to 2022, discussions within the VARRC were highly focused on vaccine safety, emphasizing potential risks while rarely addressing the clinical benefits of vaccination[8].

4.2 Lack of consensus within the medical community and professional associations

The lack of consensus within the medical community and professional associations also reinforced the MHLW’s cautious stance. Although professional organizations such as the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Japan Pediatric Society repeatedly called for the vaccination recommendations to be reinstated as soon as possible, surveys show that during this period, frontline healthcare providers themselves have often been hesitant to recommend vaccination due to the uncertainty surrounding the reported adverse events[3].

4.3 Inadequate and delayed government communication

The government’s decision to suspend active recommendations exacerbated public panic and distrust. After the suspension of active recommendations, social media platforms saw an increasing number of personal accounts of symptoms following vaccination, which fueled the spread of unconfirmed information. However, subsequent studies showed that there was no direct link between the reported symptoms and vaccination. The Japanese government still failed to respond promptly and transparently to these reports, with official guidance being inconsistent, missing an opportunity to communicate the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine to the public, and leaving negative perceptions of the vaccine among adolescents and parents widespread[2,3]. Unlike Japan, the European Medicines Agency demonstrated in 2015 that there was no causal relationship between complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and HPV vaccination, which led to a rapid recovery in vaccination rates[1].

4.4 Insufficient Knowledge Provision in Schools and Clinics

The current lack of sex education in Japan, particularly in schools, has led to limited awareness of cervical cancer among Japanese girls and their parents. Sex education in Japanese schools remains very conservative, and topics related to sexual health often considered cultural taboos, depriving young people of the opportunity to learn about female reproductive health and the importance of self-protection[9]. Pediatricians and general practitioners in Japan generally lack standardized training in HPV-related health education[10]. In addition, despite the government’s announcement in 2022 to reinstate the recommendation for HPV vaccines, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology still requires universities nationwide that offer medical education courses to include a course on adverse drug reactions, with the HPV vaccine incident being one of the course contents[11]. This may further undermine healthcare professionals’ confidence in HPV vaccines, affecting their ability to effectively communicate the safety and efficacy of the vaccine to the public.

5 Key lessons learned from the Japanese case

- First, the National Expert Committee should include experts from interdisciplinary fields to ensure the comprehensiveness and evidence-based scientific nature of policy-making.

- Second, the government must proactively, promptly, and transparently address media concerns by providing accurate and complete official information to dispel public misunderstandings and alleviate panic.

- Third, strengthening medical personnel training and public health education is crucial for improving public awareness of vaccines and diseases and enhancing public trust.

- Fourth, the government and relevant institutions should strengthen monitoring systems, early warning mechanisms, and emergency response plans to mitigate the impact of sudden incidents on public trust and social stability.

- Fifth, countries should promote international cooperation and knowledge sharing, learn from successful experiences in vaccine safety regulation, public communication, and crisis management, and jointly enhance vaccine safety and public trust.

6 Summary

Japan’s experience with HPV vaccination provides a valuable case study for the global community, highlighting how inadequate responses to safety concerns can significantly impact public trust and vaccination coverage. From initial policy formulation and failed crisis communication to gaps in health education and the absence of professional responses, Japan’s trajectory highlights critical vulnerabilities in vaccine implementation and regulation. By examining its governance shortcomings and subsequent efforts to rebuild public trust, key lessons can be drawn to inform other countries in developing more resilient, transparent, and inclusive immunization policies and crisis response strategies.

Content Editor: Ziyi Zhu

Page Editor: Ruitong Li

References:

[1] Miyagi E. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Japan[J]. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2024, 50 Suppl 1: 65-71.

[2] Ikeda S, Ueda Y, Yagi A, et al. HPV vaccination in Japan: what is happening in Japan?[J]. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2019, 18(4): 323-325.

[3] Takahashi T, Ichimiya M, Tomono M, et al. Overcoming HPV Vaccine Hesitancy in Japan: A Narrative Review of Safety Evidence, Risk Communication, and Policy Approaches[J]. Vaccines (Basel), 2025, 13(6).

[4] Suzuki S, Hosono A. No association between HPV vaccine and reported post-vaccination symptoms in Japanese young women: Results of the Nagoya study[J]. Papillomavirus Res, 2018, 5: 96-103.

[5] Fukushima W, Hara M, Kitamura Y, et al. A Nationwide Epidemiological Survey of Adolescent Patients With Diverse Symptoms Similar to Those Following Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Background Prevalence and Incidence for Considering Vaccine Safety in Japan[J]. J Epidemiol, 2022, 32(1): 34-43.

[6] Sekine M, Yamaguchi M, Kudo R, et al. Suspension of proactive recommendations for HPV vaccination has led to a significant increase in HPV infection rates in young Japanese women: real-world data[J]. Lancet Reg Health West Pac, 2021, 16: 100300.

[7] Simms K T, Hanley S J B, Smith M A, et al. Impact of HPV vaccine hesitancy on cervical cancer in Japan: a modelling study[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2020, 5(4): e223-e234.

[8] Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Table of minutes of the conferences of the Vaccine Adverse Reactions Review Committee[EB/OL][2025-08-11]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/shingi-kousei_284075.html.

[9] Nishioka E. [Historical Transition of Sexuality Education in Japan and Outline of Reproductive Health/Rights][J]. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi, 2018, 73(2): 178-184.

[10] Katsuta T, Moser C A, Offit P A, et al. Japanese physicians’ attitudes and intentions regarding human papillomavirus vaccine compared with other adolescent vaccines[J]. Papillomavirus Res, 2019, 7: 193-200.

[11] Namba M, Kaneda Y, Kotera Y. Breaking down the stigma: reviving the HPV vaccination trust in Japan[J]. Qjm, 2023, 116(11): 895-896.