Scotland is one of the four constituent nations of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, with a population of approximately 5.5 million, accounting for about 8% of the UK’s total population (1). Its economy is centered on the sectors of energy, life sciences, and financial services, contributing around 7–8% to the UK’s gross domestic product. As an important economic and cultural part of the UK, Scotland has a high degree of autonomy, with its legislative powers in areas such as health and education, and has long implemented its own public health policies (2). Since 2000, Scotland has recorded approximately 320 new cases of cervical cancer annually, with the highest incidence observed among young women aged 35–40 (3).

1. HPV Vaccination Policy Background and Roadmap

In June 2007, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization (JCVI) in the UK recommended to the Department of Health that routine HPV vaccination should be offered to girls aged 12–13 (4). This recommendation was based on a comprehensive assessment including cost-effectiveness, feasibility of school-based delivery, the timing of sexual health education in schools, and the evidence of increasing HPV risk after age 14 (5, 6). Additionally, updated economic models supported a catch-up campaign targeting girls aged 13–17 starting September 2008 (7).

Based on the JCVI’s recommendations, National Health Service (NHS) Scotland launched its HPV vaccination program in 2008 to reduce the incidence of HPV-related cancers. Beginning in September 2008, regular three-dose vaccination was provided to girls aged 12–13 (typically in the second year of middle schools), targeting approximately 25,500 girls annually (3, 8). Between September 2008 and August 2011, a catch-up program covering girls aged 13–17 aimed to reach around 77,000 individuals. Although a specific uptake goal was not set initially, an uptake rate of ≥80% was expected. In reality, coverage in the first and second years reached 91.4% and 90.1%, respectively (3, 7).

2. High Vaccination Coverage: Planning and Implementation

The HPV vaccination program in Scotland achieved remarkable success. In the first year of implementation (2008–2009), 91.4% of girls in the regular vaccination cohort completed the three-dose vaccine series, significantly higher than the UK average of 83.5%. This success continued into the second year of the program (2009–2010), with a sustained high coverage rate of 90.1% among the target population.

The design and implementation of Scotland’s HPV vaccination program exemplify a model of systematic public health intervention. During the planning phase, a comprehensive assessment led to the adoption of a school-based vaccination model, for its advantages in accessibility, efficiency, and ease of monitoring (3). All in-school girls aged 12–13 received their immunization through organized school-based sessions. (9). For adolescent girls out of school, particularly those aged over 16, local health boards had the flexibility to deliver vaccinations through general practice or dedicated immunization centers, enhancing access for hard-to-reach populations (3).

The program was managed using the PRINCE2 standardized project management framework, with a dedicated project manager responsible for overseeing workflows and managing risks. To support implementation, five specialized workstreams were established, each responsible for a key operational domain. These workstreams included representatives from public health, Health Protection Scotland, local health boards, national support agencies (data and communications teams), and the Scottish Government. All members participated on a voluntary basis. Each workstream typically held monthly meetings, with frequencies adjusted according to project phases (3).

Scotland adopted an innovative phased implementation strategy, with the regular and supplementary vaccination programs launched simultaneously in September 2008. The catch-up cohort was stratified by age, initially targeting 16–17-year-olds, then extending to 13–16-year-olds, over a three-year period. The program’s design carefully considered age-specific health needs and feasibility constraints. It also defined “hard-to-reach groups”, the high-risk populations with lower vaccination uptake due to socioeconomic disadvantage, remote locations, or healthcare access barriers. Tailored interventions such as community outreach and mobile vaccination units were introduced to address these disparities.

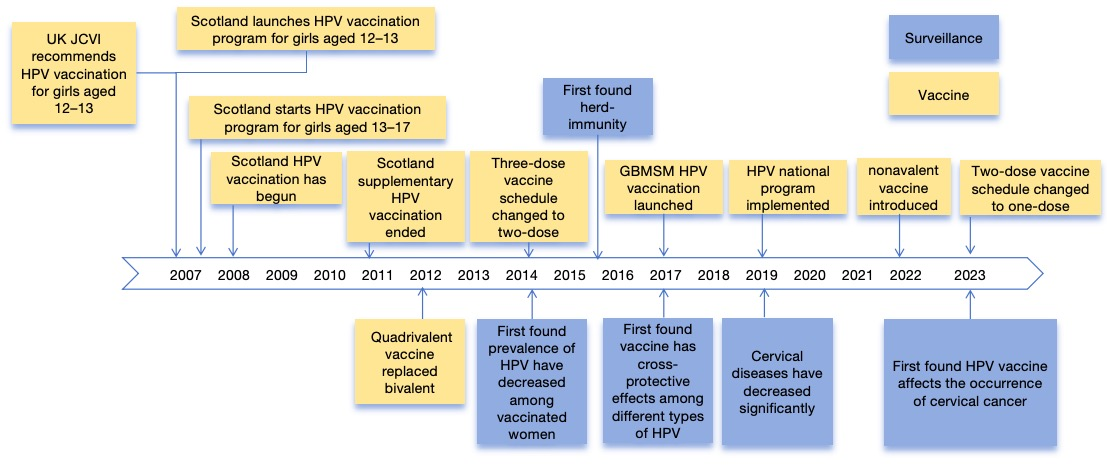

Following completion of the initial rollout, Scotland transitioned from a bivalent to a quadrivalent HPV vaccine in 2012, which also protects against genital warts. In 2014, the vaccination schedule was adjusted from a three-dose to a two-dose regimen. In 2017, the program was expanded to include gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), and in 2019 it evolved into a national HPV vaccination program. In 2022, Scotland introduced the 9-valent HPV vaccine, which protects against HPV types responsible for approximately 87% of cervical cancers. By 2023, the dosage schedule was further streamlined to a single-dose regimen, as illustrated in Figure 1 (3, 10, 11).

Figure 1 Timeline of HPV vaccination implementation in Scotland and monitoring of related diseases

3. Organizational Structure of HPV Vaccination in Scotland

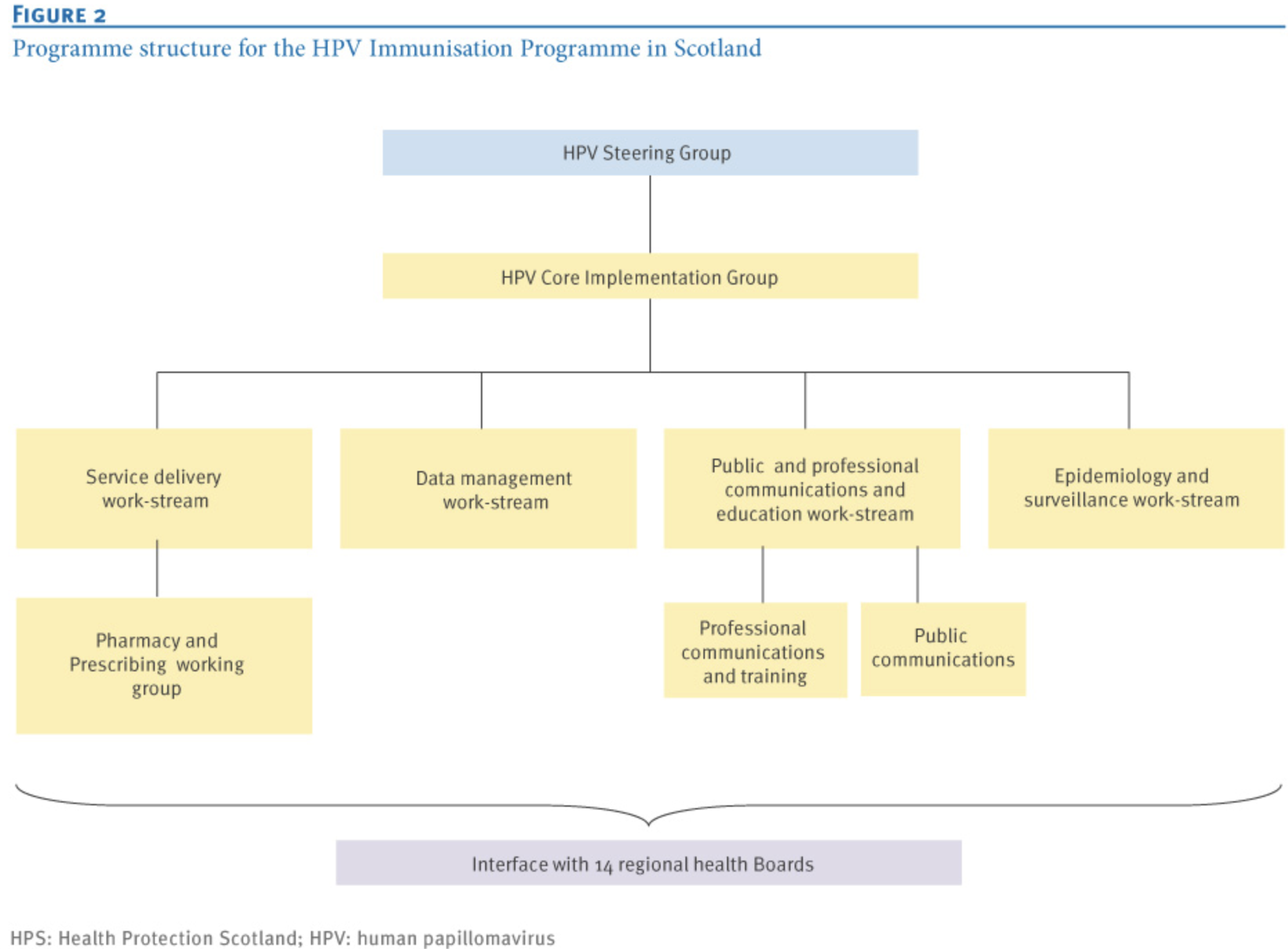

The HPV vaccination program in Scotland was driven by a coordinated network of specialized work streams, forming a clearly defined, multi-sectoral organizational structure. Under the National Steering Group, several working groups have been established, with the Service Core Implementation Working Group coordinating the overall execution of the program. key stakeholders include the Scottish Government, NHS Scotland, local health authorities, and relevant education departments (8). Under the Core Implementation Working Group, the structure includes:

- Service Delivery Workstream is responsible for ensuring that NHS comprehensively oversees HPV vaccination preparations. By establishing collaboration mechanisms with local health boards, it ensures effective alignment across local immunization service delivery, data transfer, and vaccine distribution. Under this group, the Pharmacy and Prescription Working Group oversees prescription guidelines, procurement, storage, transportation, and regulatory compliance, led by NHS pharmaceutical experts.

- Data Management Workstream is tasked with identifying the target population, optimizing the national information systems, and ensuring smooth data exchange between the education and public health sectors. Its core members include experts in data science and epidemiology.

- Public and Professional Communication and Educational Workstream is responsible for public and professional outreach, including multimedia campaigns and training for immunization staff. It is headed by senior experts in the field of health communication.

- Epidemiology and Surveillance Workstream oversees program evaluation and long-term impact monitoring, coordinating inter-regional laboratory collaborations. Its core team includes data analysts, statisticians, and public health professionals.

In addition, all working groups were horizontally integrated through a Core Implementation Team, which ensured synchronized progress via monthly meetings. Strategic decision-making and risk management were overseen by a Government Steering Group, reflecting a robust multi-level governance structure and effective cross-sectoral collaboration (3) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Organizational Structure of HPV Vaccination in Scotland

3.1 Service Delivery

This workstream ensures NHS preparedness for HPV vaccination and establishes collaboration with local health boards, covering local immunization delivery, data flow, and vaccine distribution. The Service Delivery Workstream is responsible for reviewing implementation plans from health boards, promoting the sharing of best practices, and ensuring equitable vaccine access for “hard-to-reach” populations. The group also addresses issues related to informed consent and is led by the Scottish Government, which negotiates enhanced service arrangements with primary care practitioners across the country. Its members include representatives from health boards, schools, the education sector, school nurses, general practitioners (GPs), pharmacists, and other workstreams, and it is chaired by a senior clinical public health doctor.

As a subgroup within the Service Delivery Workstream, the Pharmacy and Prescribing working group provides pharmaceutical advice and establishes protocols to ensure the safe prescription (including national patient group directions), supply, and management of vaccines. It ensures that procurement, storage, and distribution comply with relevant legal and regulatory standards and sets up local ordering and distribution systems. Progress and updates are shared through the Scottish Vaccine Update newsletter. Members include pharmacy and logistics experts and representatives from Health Boards, and it is chaired by an NHS pharmacist.

3.2 Data Management

This workstream is responsible for identifying eligible individuals for vaccination and coordinating recall and tracking mechanisms in line with the vaccination schedule. It ensures smooth data flow from invitation to record-keeping, which requires technical adjustments to national information systems and the generation of coverage data. It also ensures effective linkage between the education and public health sectors, allowing follow-up of girls who have left school. Members include specialists in system design, data analysis, epidemiology, and representatives from health boards, education, screening programs, and general practice. It is chaired by a public health physician experienced in managing national data systems.

3.3 Public and Professional Communication and Education

This workstream designs and implements multimedia campaigns to enhance acceptance of the HPV vaccine among girls, their parents, educators, and healthcare providers. Professional communication tools include stakeholder briefings, regular professional letters to service providers, and training for immunization nurses. For school-leavers, a “pink promotional bus” was used to raise awareness. Members come from communications, training, epidemiology, schools, the NHS 24-hour helpline and etc. The group is chaired by a senior communications expert from the NHS.

3.4 Epidemiology and Surveillance

This workstream develops tools to evaluate vaccine coverage and safety and monitors the vaccine’s impact on high-risk HPV infections, cervical cancer, and precancerous lesions. The aim is to provide evidence-based guidance on the balance between screening, HPV testing, and vaccination strategies. A national Scottish HPV Reference Laboratory was established, working in partnership with the UK Health Security Agency (formerly Public Health England) to ensure cross-regional monitoring consistency. Members include epidemiologists, lab representatives, statisticians, and experts from the data management group and health boards. It is chaired by a senior clinical lead for Health Protection Scotland.

3.5 Project Coordination and Oversight

The progress of all working groups is coordinated through monthly meetings of the Service Core Implementation Group, composed of group chairs, project managers, and representatives from the Scottish Government. A government-appointed Steering Group oversees the entire program, approves strategic decisions, and commissions third-party Gateway Reviews to assess risks, governance, and processes at key stages. The Steering Group meets quarterly and includes senior stakeholders from education, public health, schools, and patient advocacy. It is chaired by a senior executive from a health board not directly involved in the project.

4. Positive Impact of Vaccination

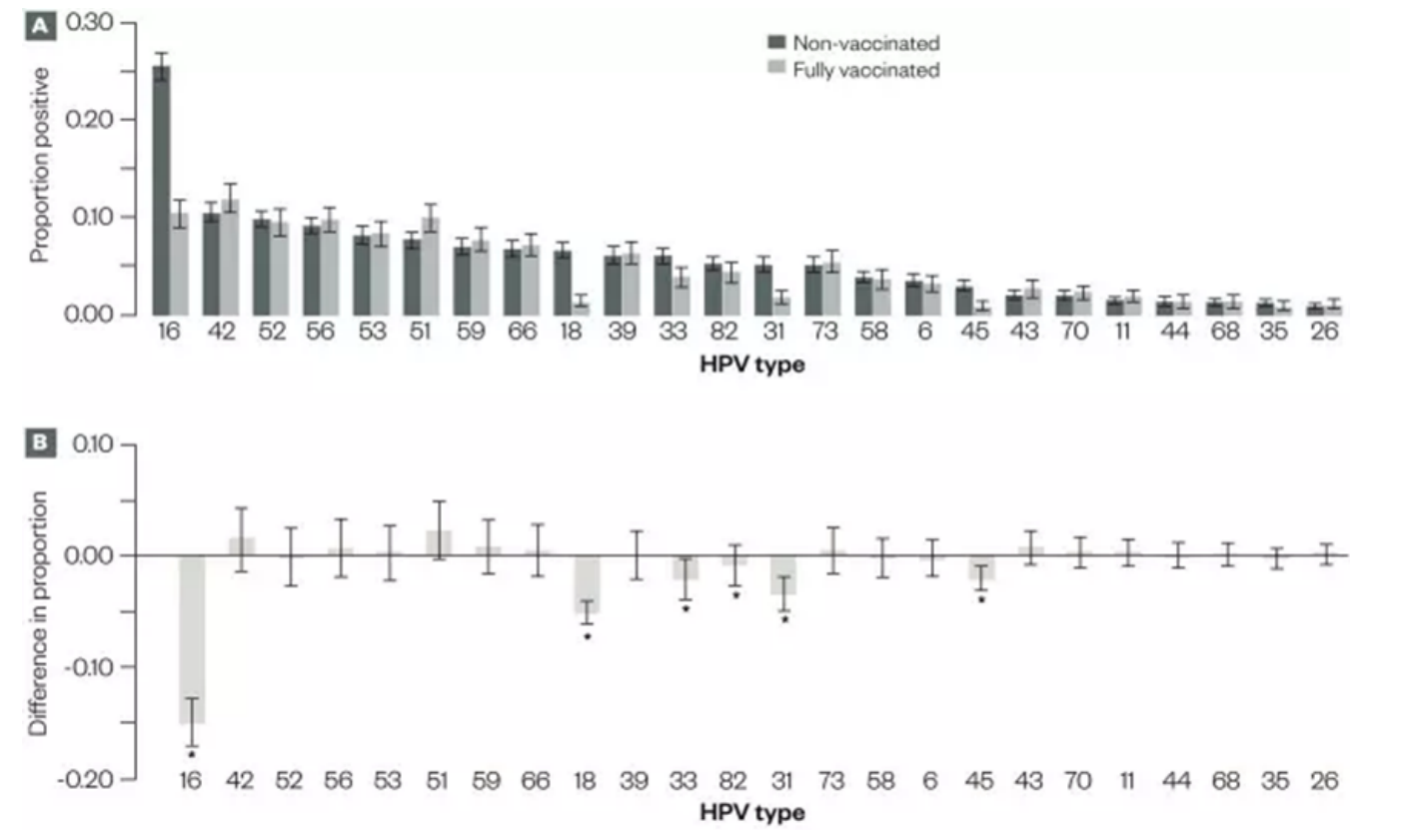

Scotland was among the first to implement bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines, both of which protect against HPV types 16 and 18, high-risk strains strongly associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Studies have shown that these vaccines induce durable neutralizing antibody responses and effectively prevent related lesions. The bivalent vaccine also offers some cross-protection against other high-risk types related to HPV 16 and 18, such as HPV 31, 33, and 45, while the quadrivalent vaccine provides partial cross-protection against HPV 31 and 33 as well (12, 13). Moreover, data indicate that among unvaccinated women in Scotland, the prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 was significantly lower in 2013 compared to 2009 (21.2% vs. 30%), suggesting a herd immunity effect resulting from the vaccination program (14). Population-based surveillance data show a strong association between HPV vaccination and reduced prevalence of both low- and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN1 and above) among young women (15). In Scotland, the administration of three doses of the bivalent vaccine led to a 50% reduction in CIN2 and a 55% reduction in CIN3 incidence. Notably, these significant effects were observed within the catch-up cohort, implying even greater effectiveness is likely in the routinely vaccinated population (14).

Figure 3: HPV testing results among vaccinated and unvaccinated women in Scotland, 2009–2013

Study findings underscore the remarkable protective effects of HPV vaccination against cervical disease and cancer. A retrospective population study published in the British Medical Journal reported that girls vaccinated with the bivalent HPV vaccine at ages 12–13 had, by age 20, an 89% reduction in CIN3 or more severe lesions, an 88% reduction in CIN2+, and a 79% reduction in CIN1.

In addition, a reduction in cervical lesion risk was also observed among unvaccinated women(16). Further confirmation came from a study published in the Lancet, which found that HPV vaccination reduced the incidence of cervical cancer by 87% among women vaccinated at ages 12–13(17). According to the latest NHS research, no cervical cancer cases have been detected among women who were fully vaccinated at those ages, highlighting the vaccine’s highly effective preventive role (10). These studies provide direct evidence of the HPV vaccine’s efficacy in cervical cancer prevention and emphasize the critical importance of early vaccination. More details can be found in Figure 1.

5. Ongoing Monitoring and Improvement

To ensure the quality of the program, Scotland established a comprehensive, multi-dimensional monitoring system that includes:

- Establish an immunization and surveillance system comprising the Scottish Child Health Surveillance Programme(Schools), the Child Health Surveillance Programme(Pre-school), and the Scottish Immunisation Recall System (7);

- Assessing the awareness and attitudes of parents, children, educators, and healthcare professionals regarding HPV, cervical cancer, and the proposed vaccine, as well as evaluating the acceptability of the information provided in public education materials;

- Developing low-cost, simple, and reliable HPV testing methods to monitor infection rates within the target vaccinated population (18-20);

- Determining baseline HPV infection rates and prevalent genotypes among unvaccinated individuals prior to the implementation of the vaccination program (21);

- Establishing a surveillance system to track vaccination coverage, safety, and early outcomes, primarily by analyzing changes in HPV infection rates among women undergoing cervical screening, as a way to assess the initial impact of vaccination;

- Identifying demographic and behavioral differences between women who attend cervical screening and those who do not(22), in order to evaluate the representativeness of the screening sample and ensure that monitoring results are broadly applicable to the female population in Scotland.

6. Summary

Despite the program’s significant achievements, health authorities in Scotland continue to monitor the effectiveness of the HPV vaccination strategy and adjust their approach based on the latest research and data to maintain high coverage and efficacy. Scotland’s success in HPV vaccination offers valuable insights for other regions, demonstrating that systematic planning and broad collaboration can yield substantial public health benefits.

Content Editor: Ziyi Zhu

Page Editor: Ruitong Li

References:

1. G. Y. Ho, R. Bierman, L. Beardsley, C. J. Chang, R. D. Burk, Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med 338, 423-428 (1998).

2. S. Government, Scottish economic outlook (2024).

3. A. Potts et al., High uptake of HPV immunisation in Scotland–perspectives on maximising uptake. Euro Surveill 18 (2013).

4. D. o. H. (DH), Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI). JCVI meeting minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday 20 June 2007 at 10.30am. [Accessed 25 Sep 2013]. (2013).

5. M. Jit, Y. H. Choi, W. J. Edmunds, Economic evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United Kingdom. Bmj 337, a769 (2008).

6. J. C. o. V. a. Immunisation (2007) Minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday 20 June 2007 at 10.30am.

7. T. S. Government (2008) Public Health and Wellbeing Directorate. Implementation of Immunisation Programme: Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Vaccine – Project Update including the Catch Up Campaign. .

8. T. S. Government. (2007) Public Health and Wellbeing Directorate. Implementation of Immunisation Programme: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine.

9. K. Sinka et al., Achieving high and equitable coverage of adolescent HPV vaccine in Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health 68, 57-63 (2014).

10. P. H. Scotland (2024) No cervical cancer cases detected in vaccinated women following HPV immunisation.

11. T. J. Palmer et al., Invasive cervical cancer incidence following bivalent human papillomavirus vaccination: a population-based observational study of age at immunization, dose, and deprivation. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 116, 857-865 (2024).

12. J. Paavonen et al., Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet 374, 301-314 (2009).

13. S. N. Tabrizi et al., Assessment of herd immunity and cross-protection after a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in Australia: a repeat cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 14, 958-966 (2014).

14. C. Pharmacist, The impact of the human papillomavirus vaccine in Scotland: a changing landscape. Pharmaceutical Journal 9 (2017).

15. K. G. Pollock et al., Reduction of low- and high-grade cervical abnormalities associated with high uptake of the HPV bivalent vaccine in Scotland. Br J Cancer 111, 1824-1830 (2014).

16. T. Palmer et al., Prevalence of cervical disease at age 20 after immunisation with bivalent HPV vaccine at age 12-13 in Scotland: retrospective population study. Bmj 365, l1161 (2019).

17. M. Falcaro et al., The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet 398, 2084-2092 (2021).

18. W. Forson et al., High-risk HPV mRNA testing on self-samples offered to those who do not attend for organised cervical screening – real world data from the Dumfries and Galloway region in Scotland. J Clin Virol 175, 105734 (2024).

19. K. Cuschieri et al., Urine testing as a surveillance tool to monitor the impact of HPV immunization programs. J Med Virol 83, 1983-1987 (2011).

20. K. Cuschieri et al., Effect of HPV assay choice on perceived prevalence in a population-based sample. Diagn Mol Pathol 22, 85-90 (2013).

21. M. C. O’Leary et al., HPV type-specific prevalence using a urine assay in unvaccinated male and female 11- to 18-year olds in Scotland. Br J Cancer 104, 1221-1226 (2011).

22. K. Sinka et al., Acceptability and response to a postal survey using self-taken samples for HPV vaccine impact monitoring. Sex Transm Infect 87, 548-552 (2011).