Australia pioneered a national Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program in 2007, recognized globally as an exemplary case of HPV vaccination implementation. After more than a decade of implementation, Australia has achieved remarkable results and is poised to become the first country in the world to eliminate cervical cancer[1]. This article summarizes the implementation experience of Australia’s HPV vaccination program to provide reference for other countries and regions.

Policy Background and Development History

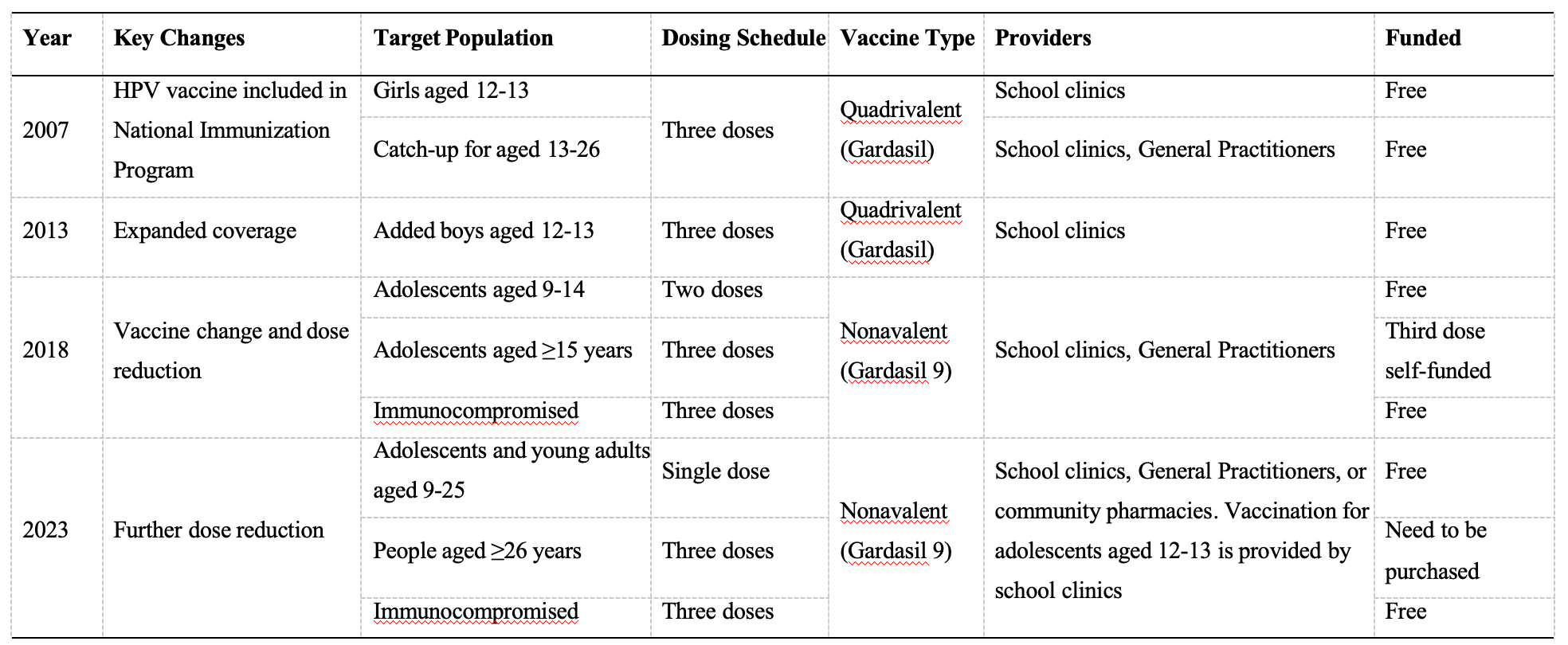

In 2006, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia approved the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil®) for females aged 9-26. In 2007, the Australian government swiftly incorporated the HPV vaccine into the National Immunisation Program (NIP), providing free three-dose quadrivalent vaccination for girls aged 12-13. As scientific evidence accumulated, Australia continuously adjusted its vaccination protocol.

- 2007 year: HPV vaccine was included in the National Immunisation Program (NIP), providing free quadrivalent vaccine through schools for girls aged 12-13, using a three-dose schedule (0, 2, 6 months).During the same period, Australia launched two catch-up programs: one targeting female students aged 13-17 in schools, and another implemented from July 2007 to December 2009 through general practitioners for adult women aged 18-26 [2]. Each state adopted different approaches based on their circumstances, implementing phased rollouts for female students in different grades [3]. For example, in Victoria, Australia’s second most populous state, the secondary school HPV vaccination program began on April 16, 2007. In 2007, free vaccination was provided to female students in Grade 7 (ages 12-13) and Grades 10-12 (ages 15-18). In 2008, free vaccination was provided to the remaining two catch-up groups of female students (who were 13-14 and 14-15 years old respectively in 2007) [2].

- 2013 year: Vaccination coverage was expanded to include boys aged 12-13, making Australia one of the first countries in the world to implement gender-neutral HPV vaccination[4].

- 2018 year: The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil®) was replaced with the nonvalent vaccine (Gardasil®9), and the vaccination schedule for adolescents aged 12-13 (both female and male) was reduced from three doses to two doses, with at least 6 months between doses for those under 15 years of age. Simultaneously, free catch-up vaccination with two doses was provided for individuals up to 19 years old. Individuals aged 15 and above still required three doses, as did immunocompromised individuals regardless of age [5].

- 2023 year: The routine two-dose HPV vaccination schedule for adolescents aged 12 to 13 was changed to a single-dose schedule using the same Gardasil®9 vaccine; simultaneously, the catch-up program upper age limit was extended from 19 to 25 years. Immunocompromised individuals still require three doses[6].

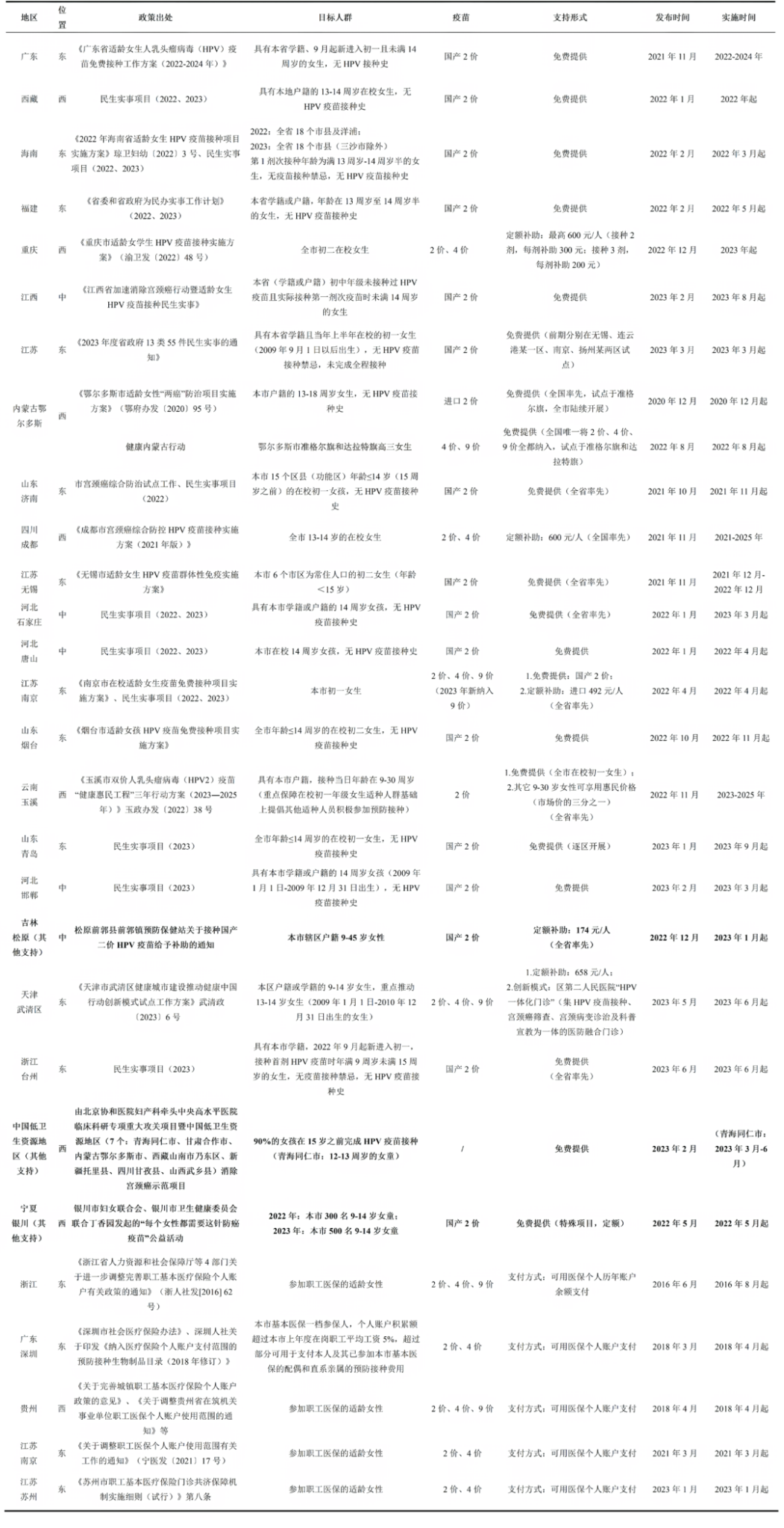

Table 1 Timeline of Australia’s HPV Vaccination Strategy

Effectiveness and Impact

Vaccination Coverage Rates Remain among the Highest Globally

According to data released by the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) in Australia, as of 2020, 80.5% of girls and 76.5% of boys had completed the two-dose HPV vaccination series before the age of 15. This coverage rate is much higher than that in most countries that have implemented the program. With the shift to a single-dose schedule in 2023, the full – course vaccination rate further increased. In 2023, 84.2% of girls and 81.8% of boys received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine before the age of 15[7].

Substantial Reduction in Disease Burden

Numerous studies have demonstrated the remarkable effectiveness of Australia’s HPV vaccination program. A repeat cross-sectional study showed that prevalence of cervical HPV types targeted by the quadrivalent vaccine has declined by 92% among 18- to 35-year-old Australian women 9 years following implementation of vaccination[8]. 2011, five years after HPV vaccines were included in the immunization program, the proportion of women under 21 diagnosed with genital warts dropped dramatically, from 11.5% in 2007 to 0.85% in 2011 [9]. In Victoria, five years after the implementation of the HPV vaccination program, the incidence of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+) among women aged 20-23 decreased by 48% [10]. Reports predict that Australia’s cervical cancer incidence rate is expected to drop to <4 per 100,000 by 2035, achieving the WHO-set goal of “cervical cancer elimination” [11]. These achievements highlight the public health value of HPV vaccination programs and their herd immunity effects.

Analysis of Success Factors

Strong Policy and Financial Support

The Australian federal government has provided firm policy and financial support for the HPV vaccine program. In 2023, the Australian government announced an investment of 48.2 million Australian dollars over the next 4 years to improve accessibility to cervical cancer screening and follow-up services, and to enhance data acquisition on population immunization [12]. Adequate financial support effectively eliminates economic barriers to program advancement and promotes widespread vaccination.

Evidence-based Policy Adjustments

Australia continuously adjusts its vaccination strategies based on the latest scientific evidence. The government respects and adopts the scientific advice provided by professional advisory bodies, such as the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). It aligns with the recommendations of international organizations, mainly the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE). The government regularly evaluates international research data and local implementation experiences, promptly incorporating the latest research findings, such as evidence of the effectiveness of the single-dose regimen. This emphasis on evidence-based decision-making ensures the scientific integrity of Australia’s vaccination policies[5].

Multilevel Service System

To ensure comprehensive coverage, Australia has established a multilevel service system. School-based vaccination is the main route, covering most adolescents; general practitioner clinics and community pharmacies can provide services for those who were unable to be vaccinated at school; and Aboriginal health services can offer culturally appropriate services for the Indigenous population. These services include developing culturally sensitive promotional materials, promoting the vaccination program through Indigenous community leaders, and providing mobile vaccination services in remote areas. This multilevel system ensures vaccine accessibility through different channels, reflecting the flexibility and inclusiveness of Australia’s HPV vaccination program [5,11].

School-based vaccination ensures coverage of priority target populations

Australia’s tradition of providing voluntary school-based vaccination for adolescents began in the 1970s, incorporating vaccination into routine school health services, with professional nurses administering vaccines and requiring parental informed consent. The HPV school-based vaccination program has received strong support from parents and communities because vaccination is convenient, families do not need to pay fees, and it saves parents’ energy and time; on vaccination days, peer support forms among adolescents [13]. Various social levels also provide support for school vaccination. For example, Australian universities have established specialized courses for secondary school teachers to enhance their knowledge and understanding of HPV vaccines, helping to promote HPV immunization [14].

Effective Public Education and Communication

In response to vaccine hesitancy and safety concerns, Australia has adopted a scientific and transparent communication strategy, including: the government publishing HPV vaccination recommendation updates on official websites and providing publicly accessible HPV vaccine Q&A materials [15, 16], providing parents and adolescents with evidence-based scientific information materials, emphasizing the key role of HPV vaccines in eliminating cervical cancer. Health departments also provide professional HPV vaccine immunization manuals for healthcare workers, detailing national immunization program policies, vaccination recommendations for different risk groups, and evidence-based rationales [6, 17]. Health departments maintain open media communication channels, promptly responding to media inquiries about vaccine safety, and maintaining transparent information communication. Additionally, non-governmental organizations, industry associations, and others actively participate in HPV vaccine science popularization and public communication [18].

Comprehensive Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanism

Since Australia’s childhood vaccine registration system cannot cover adolescent vaccines, to promote effective implementation of the HPV vaccination program, Australia established the National Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Program Register (NHVPR) through legislation to assist in monitoring vaccination coverage rates. Each state has varying degrees of immunization safety monitoring, while comprehensive data system connectivity enables the development of risk management strategies, effective and rapid handling of adverse events, and maintains public and healthcare worker confidence in vaccines [19]. Australia also evaluates vaccine implementation and effectiveness by integrating cervical cancer screening system data and HPV epidemiological survey data, providing scientific evidence for policy adjustments.

Implications for Other Countries

Australia’s successful experience provides valuable insights for other countries and regions. First, the firm commitment and continuous financial support from the government are crucial; second, a multilevel service system can ensure comprehensive coverage and the school-based vaccination model is an effective way to increase coverage rates; in addition, evidence – based communication and education are key to addressing vaccine hesitancy; finally, a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation system can promote the continuous improvement of the program.

The successful implementation and remarkable effectiveness of Australia’s HPV vaccination program demonstrate the power of comprehensive and systematic public health interventions. Australia is expected to be the first to eliminate cervical cancer within the next decade, and its implementation model and experience are worthy of global reference, offering a practical path for countries around the world to eliminate the disease burden associated with HPV.

Reference

[1] Hall M.T., Simms K.T., Lew J.B., et al. The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in australia: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2019, 4(1): e19-e27.

[2] Brotherton J.M., Fridman M., May C.L., et al. Early effect of the hpv vaccination programme on cervical abnormalities in victoria, australia: An ecological study. Lancet. 2011, 377(9783): 2085-2092.

[3] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. (n.d.). Department of Health and Aged Care | Interim estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage in the school-based program in Australia. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-cdi3204i.htm

[4] Smith M.A., Canfell K. Incremental benefits of male hpv vaccination: Accounting for inequality in population uptake. PLoS One. 2014, 9(8): e101048.

[5] Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer, Development of a national cervical cancer elimination strategy technical paper. 2022.

[6] Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), Australian immunisation handbook, C.A.G.D.o. Health, Editor. 2023.

[7] Hull B., Hendry A., Macartney K., et al., Annual immunisation coverage report 2023, in Sydney: National Centre For Immunisation Research and Surveillance. 2024.

[8] Machalek D.A., Garland S.M., Brotherton J.M.L., et al. Very low prevalence of vaccine human papillomavirus types among 18- to 35-year old australian women 9 years following implementation of vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2018, 217(10): 1590-1600.

[9] Ali H., Donovan B., Wand H., et al. Genital warts in young australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: National surveillance data. Bmj. 2013, 346: f2032.

[10] Garland S.M., Kjaer S.K., Muñoz N., et al. Impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: A systematic review of 10 years of real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2016, 63(4): 519-527.

[11] Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer. (2023). NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR THE ELIMINATION OF CERVICAL CANCER IN AUSTRALIA. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-11/national-strategy-for-the-elimination-of-cervical-cancer-in-australia.pdf

[12] Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing. (2023, November 17). Making history by eliminating cervical cancer in Australia and our region. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-ged-kearney-mp/media/making-history-by-eliminating-cervical-cancer-in-australia-and-our-region

[13]Davies, C., Stoney, T., Hutton, H., Parrella, A., Kang, M., Macartney, K., Leask, J., McCaffery, K., Zimet, G., Brotherton, J. M., Marshall, H. S., & Skinner, S. R. (2021). School-based HPV vaccination positively impacts parents’ attitudes toward adolescent vaccination. Vaccine, 39(30), 4190–4198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.051

[14] Co-designing HPV vaccination professional development for teachers and school staff: A Collaborative Approach with Key Stakeholders in Health and Education. (2025, July 1). The University of Sydney. https://www.sydney.edu.au/infectious-diseases-institute/news-and-events/news/2025/07/01/co-designing-hpv-vaccination-professional-development-for-teachers.html

[15] NCIRS. (2018b). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines for Australians | NCIRS Fact sheet: April 2018. In NCIRS Fact Sheet. https://www.ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2018-12/HPV%20Factsheet_2018%20Aug%20Update_final%20for%20web.pdf

[16] NCIRS. (2018a). HPV vaccine – FAQ. In NCIRS Fact Sheet. https://www.ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2018-12/HPV%20Frequently%20Asked%20Questions_2018%20Update_Final%20for%20web.pdf

[17] Leask J., Kinnersley P., Jackson C., et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: A framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12: 154.

[18] Support, G. C. (2025, July 23). School education. ACCF. https://accf.org.au/school-education/

[19] Garland, S. M. (2014). The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clinical Therapeutics, 36(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005