Amid China’s ongoing advocacy for its “Integration of Treatment and Prevention” strategy and the transition of its healthcare system from a “treatment-centered” to a “health-centered” model, the Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) held an online seminar titled “Vaccine Literacy and Advocacy: Empower Physicians in China“ on November 20, 2025.

The event brought together experts from China and Australia to explore the crucial role of healthcare providers in strengthening public confidence in vaccines, improving immunization coverage, and implementing the “Integration of Treatment and Prevention” model, examining the issue from three distinct perspectives: cognitive psychology, clinical practices, and hospital management.

Waning Vaccine Confidence and the Key Role of Physicians

Over the past decade, vaccine confidence has shown a worrying decline globally. Although the COVID-19 pandemic thrust vaccines into the global spotlight like never before, signs of vaccine hesitancy were apparent even before the pandemic. This phenomenon is not unique to any single country but is driven by a complex mix of social, political, and informational factors, posing a persistent threat to infectious disease control and prevention.

“Vaccine hesitancy has become more pronounced, which is partially due to the great success of immunization programs. People have forgotten the dangers of the diseases,” explained Dr. Ketaki Sharma, a pediatrician and vaccinology expert from the Australian National Centre for Immunization Research and Surveillance (NCIRS). She noted that formerly common infectious diseases, like measles and polio, are now rarely seen. With fewer people witnessing cases firsthand, attention shifts more easily to potential vaccine side effects.

Furthermore, the spread of misinformation or disinformation presents a major challenge to public health programs, including immunization. During the workshop, Dr. Tian Ye, Deputy Director of the Infectious Diseases Department and Head of the Vaccination Consultation Clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, pointed out that while the public now has more channels to access vaccine information, misinformation such as “vaccines are harmful” or “too many vaccines weaken the immune system” has also spread, contributing to a decline in public willingness to vaccinate.

“The platform algorithms are interests’ based. The more you try to find out about the potential ‘drawbacks’ of vaccines, the more the platform feeds you information about these ‘drawbacks.’ It’s difficult for lay people to discern the scientific validity behind the information, leading to misconceptions,” said Dr. Tian.

In this context, the advice and communication from clinicians often play a decisive role in patients’ vaccination decisions.

Dr. Ketaki Sharma pointed out that in Australia, most people get vaccinated based on a doctor’s recommendation. A very small portion not only refuse vaccination but also deny the science behind immunization, preferring to believe misinformation. However, many more people fall somewhere in between. “When parents are undecided and cautious about vaccinating their children, the healthcare professional’s recommendation often has a huge impact on their final decision,” she noted.

Dr. Tian held a similar view and explained the motivation behind it: “The public tends to trust doctors’ knowledge and experience, believing that doctors can provide advice that is better tailored to their specific health conditions.”

Communication Skills are Vital, and Building Trust Requires Long-term Efforts

Both Dr. Tian and Dr. Ketaki Sharma regularly field numerous questions about immunization from patients or parents in their vaccination consultation clinics. During the workshop, they shared common questions they encounter and effective communication strategies for different types of concerns.

Acknowledging and addressing the core concerns of patients, while avoiding overwhelming them with extensive data or overly technical jargon, was a communication principle both emphasized. “Use plain language to explain how vaccines prevent disease, rather than relying solely on professional terminology. While our expertise is valuable, patients can find it difficult to understand, and clinical consultation time is very limited,” Dr. Tian stated.

Dr. Ketaki Sharma stressed that a doctor’s response should be a “clear, strong, and personalized recommendation.” She addressed common cognitive biases related to immunization and proposed corresponding communication strategies. For instance, some parents exhibit risk aversion bias – “I’d rather risk natural infection than have my child get the vaccine.” In such cases, she explains to parents that inaction (i.e., not vaccinated) also carries serious consequences, such as increasing the risk of contracting infectious diseases and suffering from their potential sequelae.

Dr. Tian summarized communication strategies tailored to different demographic groups. For children, using pictures, brochures, adjectives, or references to cartoons can be effective. For adults, especially those with technical or scientific backgrounds, data carries more weight. For elderly individuals, colloquial expression is essential.

Consultation time at the clinic is limited, and both Dr. Ketaki Sharma and Dr. Tian believe that trust-building is a long-term effort that requires concrete implementation mechanisms.

Dr. Ketaki Sharma shared practices from specialized immunization clinics in New South Wales, Australia. As consultations with general practitioners are often time-limited, these specialized clinics allow parents to book appointments for thorough discussions about their immunization questions.

“If needed, we can talk for an hour or even schedule a follow-up in-person appointment. For families with children with special health conditions, or for parents with many concerns, we might suggest alternative vaccines or offer a temporary exemption – giving them more time to think and gradually build trust. Furthermore, we can offer some flexibility within guidelines, for example, by slightly extending the interval between doses,” she explained.

Dr. Tian builds long-term trust by establishing parent WeChat groups to answer questions. He also collaborates with the Nanjing Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to set up vaccination education workshops, maintaining open channels for discussion and thorough exchange on immunization-related issues. “With trust established, we can achieve better goals: first, providing the service, and second, helping parents build confidence in vaccines.”

“Integration of Treatment and Prevention” is Feasible; Doctors Need Systemic Support

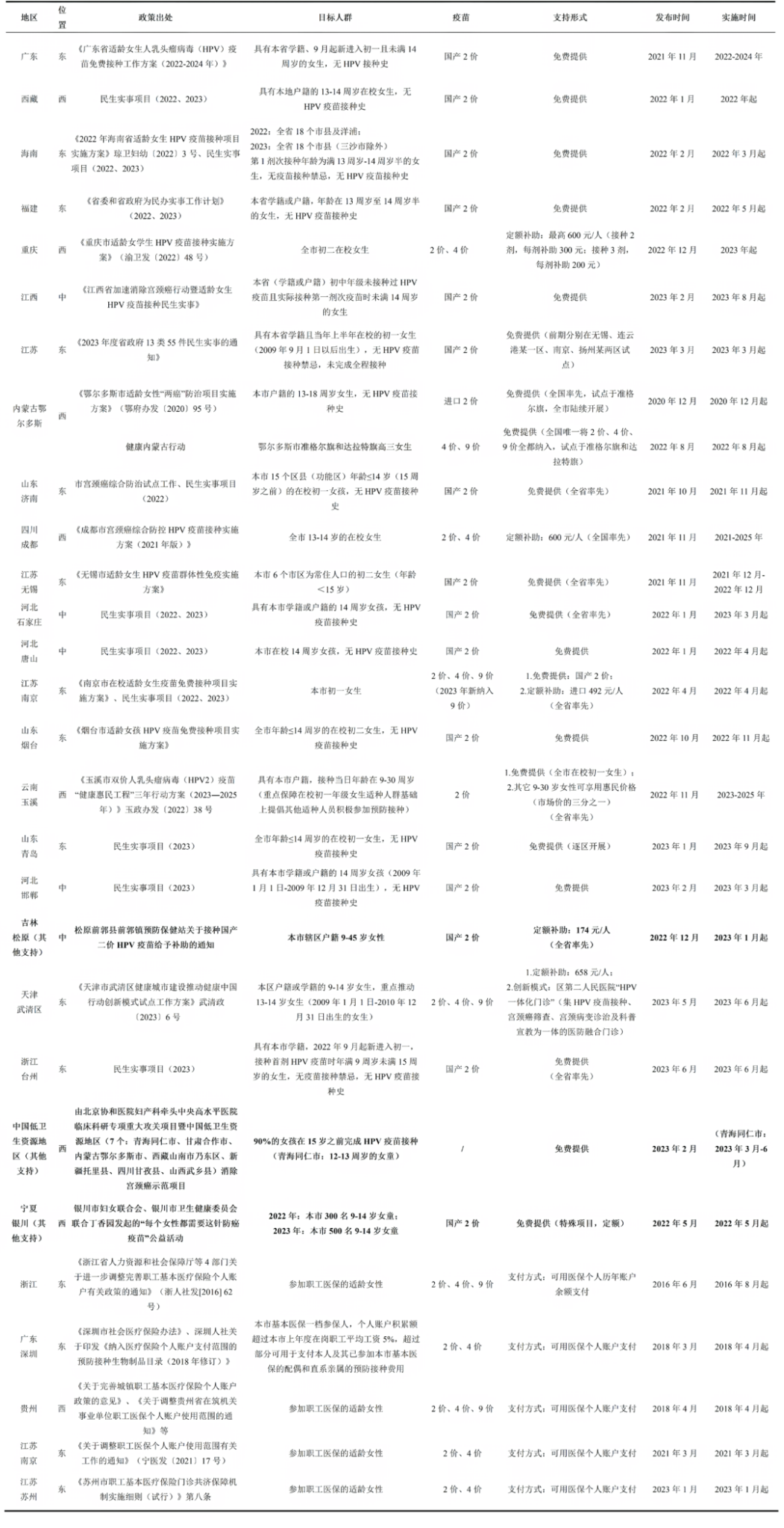

Public information shows that in recent years, some regions in China have pioneered the exploration of various types of vaccination clinics within tertiary hospitals, including maternity vaccination clinics, rabies post-exposure prophylaxis clinics, and adult vaccination clinics.

Dr. Liu Si, Deputy Chief Physician of the Emergency Department at Peking University First Hospital, shared his hospital’s experience in establishing an HPV vaccination clinic at the workshop. The clinic was launched in 2019 and was upgraded in 2025 to an “HPV-Related Disease Prevention and Control Integrated Clinic,” establishing a full-process management system covering “vaccination – screening – diagnosis/treatment – follow-up.”

Dr. Liu Si believes tertiary hospitals have three main advantages in engaging in public health work: influential clinicians, large patient volume, and multiple clinical scenarios. The first aspect reflected in strong baseline doctor-patient trust and the academic standing of the specialists. Secondly, a high volume of outpatient and emergency visits ensures a broad reach. Multiple clinical scenarios provide numerous opportunities and settings for vaccine education – for instance, emergency doctors treating patients with respiratory infections in autumn and winter can opportunistically educate them about influenza vaccine uptake.

Dr. Liu Si analyzed the challenges healthcare institutions face in implementing the “Integration of Treatment and Prevention” model from four aspects: legal and qualification requirements, management of clinical space and cold chain resources, human resource allocation, and the role of doctors. Based on existing legal regulations, facilities, and resource allocation in tertiary hospitals, he indicated that the first three aspects “are not difficult to implement.”

Regarding the role of doctors, there might be a misconception that “if prevention is done well, there will be fewer patients.” Dr. Liu Si stated that disease prevention is a major societal trend. Using the disease burden of hepatitis B as an example, he noted that as immunization rates increased, the incidence of hepatitis B-related diseases indeed decreased – for instance, the number of surgeries for portal hypertension dropped. However, hepatobiliary surgery has since developed new specializations, such as liver tumors and biliary tract tumors. Moreover, the “evolution of the disease spectrum” resulting from vaccine prevention is relatively slow, giving healthcare institutions ample time to explore and identify new directions for service development. “Clinical doctors should actively embrace the concept of ‘Integration of Treatment and Prevention’,” he urged.

The Vaccination Consultation Clinic and the Post-Vaccination Adverse Effect Management Clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University have been operating successfully for five years. The hospital also plans to launch vaccination clinics for children with special health conditions within the next 1-2 years. Dr. Tian pointed out that the hospital already works closely with the Nanjing CDC. When community vaccination sites encounter complex pediatric issues, they refer them to the hospital’s Vaccination Consultation Clinic. “This model ensures that we use our specialized expertise to help children with various underlying health conditions. After our evaluation, they can get back on track with timely vaccination,” Dr. Tian explained.

Reflecting on practical experience, Dr. Tian noted that while most doctors are experts in their own specialties, their knowledge regarding immunization is often insufficient. Healthcare professionals need more systematic support in vaccine communication. Secondly, better coordination throughout the entire process between clinical settings and public health sector is needed. “If a doctor provides a vaccination recommendation, but the community vaccination site cannot implement it, parents will perceive a breakdown in the continuity of care within the healthcare system.”

“Many doctors are also patients themselves and may have doubts about medications or vaccines, so they also need more training and should be approached and guided with the same mindset as laypersons. Doctors are only familiar with their own specialties; sometimes there is still much to learn in the field of immunization, and we also need the CDC to have a stronger voice within clinical sector,” Dr. Tian concluded.