Overview of worldwide national immunization programs

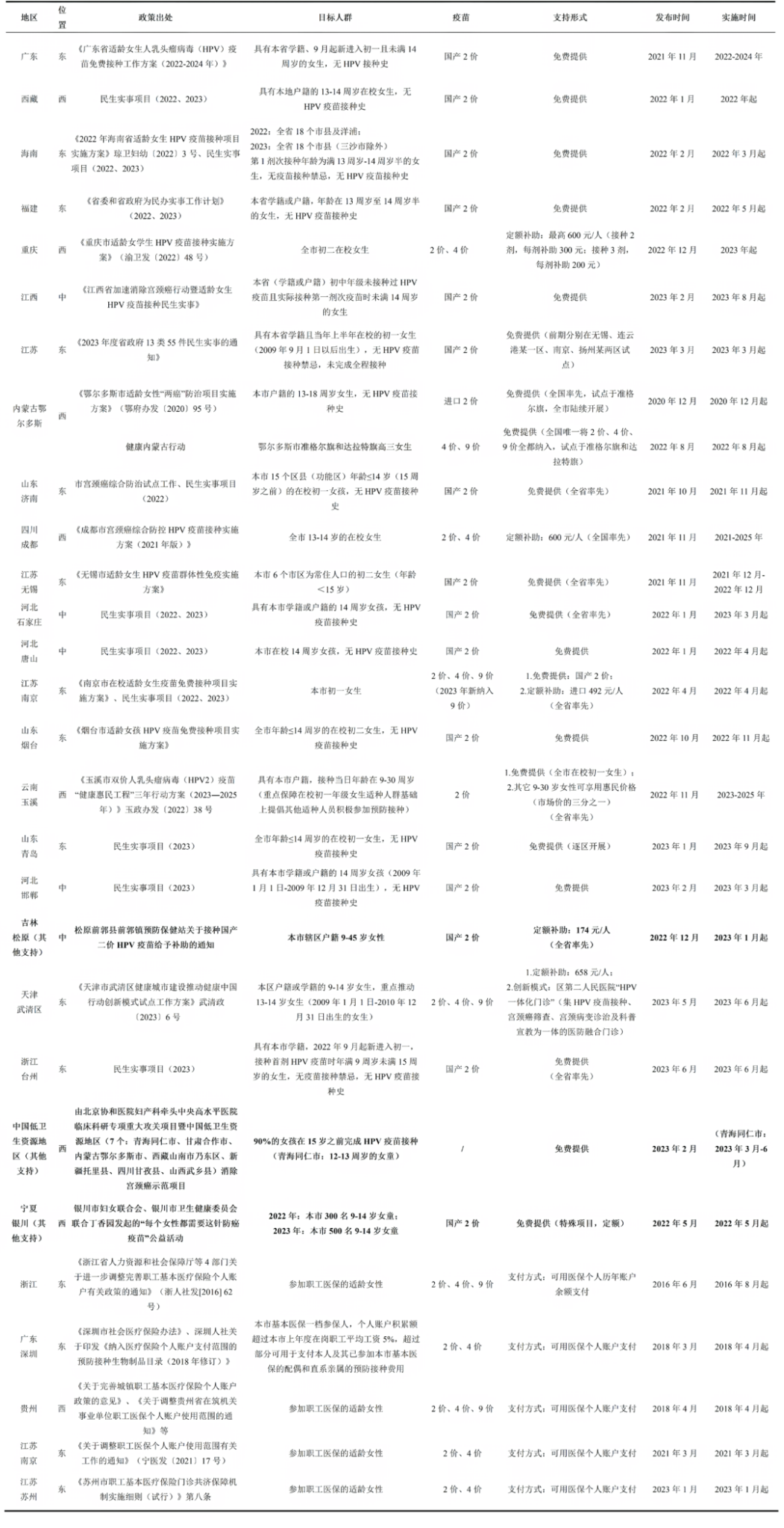

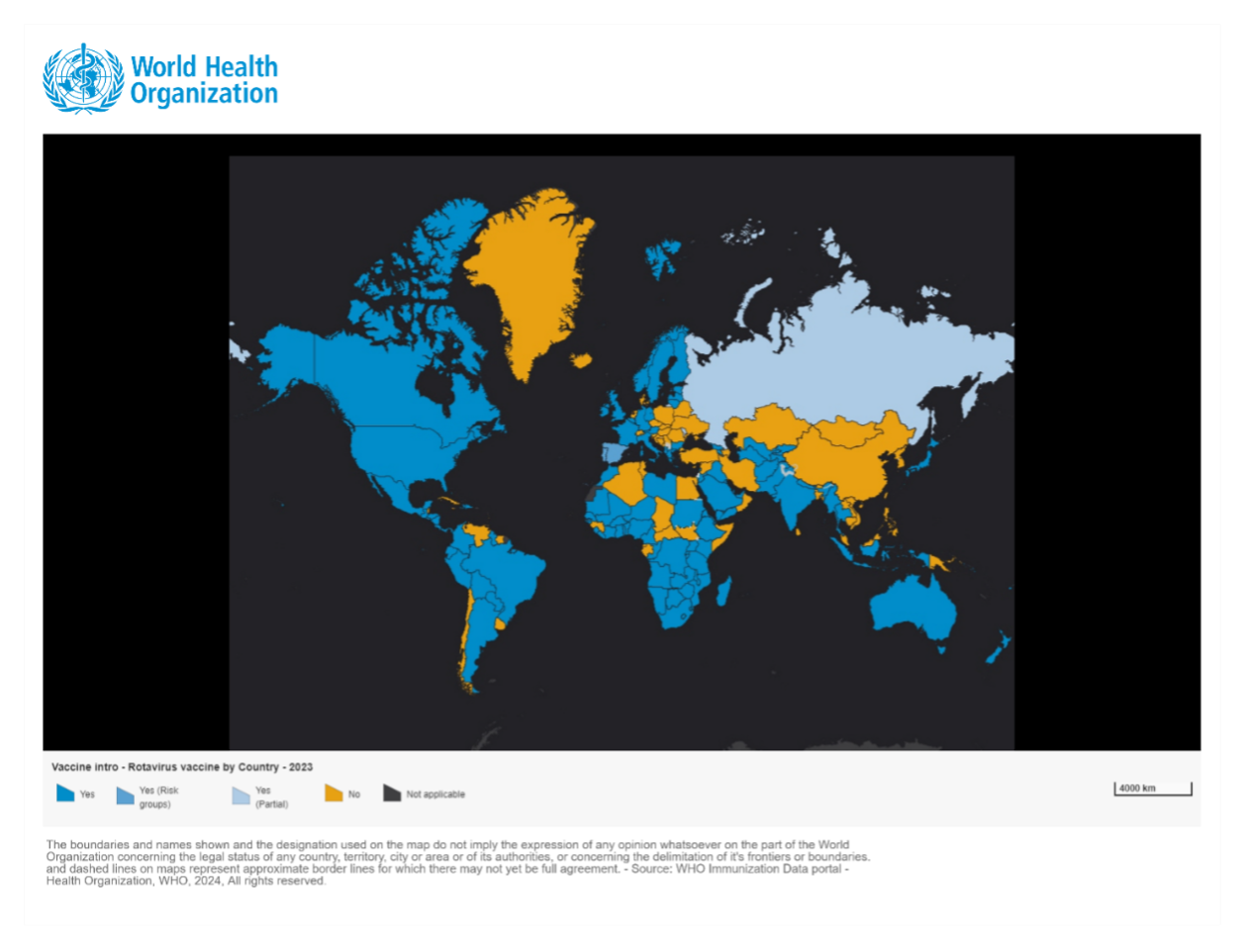

For countries where vaccine efficacy data demonstrate significant public health benefits, adequate infrastructure, and financing mechanisms, the World Health Organization (WHO) strongly recommends the inclusion of the rotavirus (RV) vaccine in their National Immunization Programs (NIPs). Based on ViewHub statistics, by November 2024, a total of 126 countries have included the RV vaccine in their NIPs.1 As of 2022, approximately 77 million infants, representing 57% of the global infant population, live in countries or regions where the RV vaccine has been introduced. 2

Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries have primarily included the RV vaccine into their NIPs with support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. As of 2023, 45 out of 57 Gavi-eligible countries have included the RV vaccine in their NIPs.3 As of October 30, 2022, 38 out of 47 countries (80%) in the WHO African Region have introduced the RV vaccine into their NIPs, with over 30 countries receiving Gavi support. Among these 38 countries, Nigeria, Congo, and Benin introduced the RV vaccine for the first time using vaccines produced in India (Rotavac or Rotasiil). Due to factors such as the withdrawal of Rotateq from the Gavi market, cold chain challenges, and procurement cost issues, 5 out of the 35 countries that initially introduced Rotateq or Rotarix have also switched to vaccines from India (Rotasiil).4

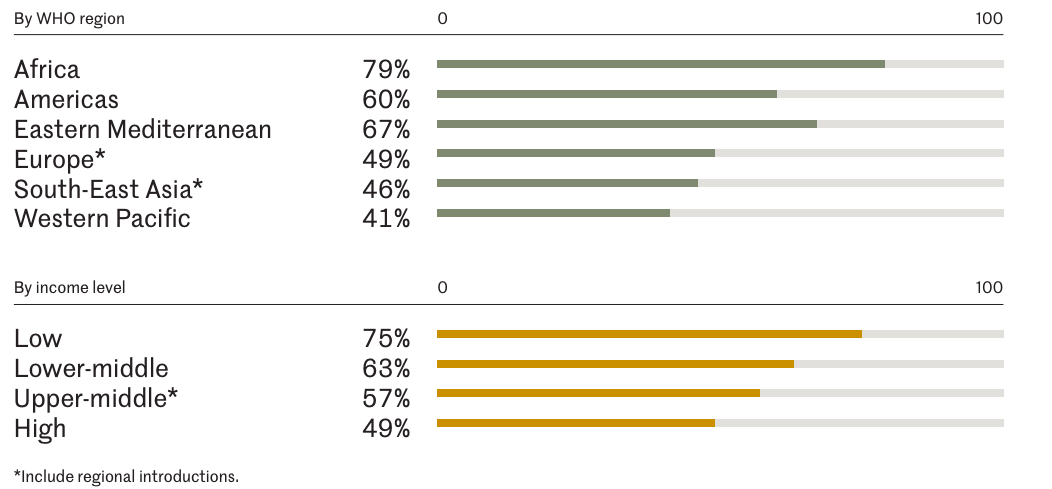

In high-income and upper-middle-income countries, the proportion of countries that have included the RV vaccine in their NIPs is lower than those low- and lower-middle-income countries. Most of the countries that have not yet included the vaccine are those that do not meet Gavi’s eligibility criteria. Among high-income countries, approximately 49% have included the RV vaccine in their NIPs, while the proportion in upper-middle-income countries is 57% by 2022. In the same year, the low-income and lower-middle-income group, the percent of countries introduced RV vaccine were 75% and 63%, respectively.2 Among non-Gavi-supported countries, 56 countries have not yet included the RV vaccine in their NIPs3, accounting for 80% of the global countries that have not adopted the vaccine. These countries are primarily located in the Western Pacific Region and Southeast Asia, with the latter region experiencing a significant disease burden caused by rotavirus.

Globally, 58.6 million children remain uncovered by RV vaccine, with approximately 70% of these children live in just 10 countries.2 China, with a huge population, has 29% of the globally RV-unvaccinated children, followed by Nigeria (12%), Indonesia (8%), Bangladesh (5%), Egypt (4%), Philippines (4%), Vietnam (3%) (began a phased regional rollout with Gavi support in 2023 5), Iran (3%), Turkey (2%), and Sudan (2%).2

The Recommended RV Vaccination Schedules by Countries

High-Income Countries in Europe and the Americas

In high-income countries, the earliest schedule for first does RV vaccination is consistent for most of them, typically starting at 6 weeks of age. The latest schedule for the first dose is generally 15 weeks, with some exceptions like Finland, which recommends 12 weeks. These timelines ensure protection during the most vulnerable period. The latest recommended age for the final dose varies. Countries using Rotarix typically recommend completion by 6 months (24 weeks), while those using RotaTeq recommend completion by 8 months (32 weeks) (see Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 RV vaccine Recommended Schedules in Specific High-Income Countries

| Country | Vaccine Type & Schedule | Earliest Age for First Dose | Latest Age for First Dose | Latest Age for the last Dose | Co-administration with Other Vaccines |

| USA | Rotarix: 2 doses at 2 & 4 months; RotaTeq: 3 doses at 2, 4, & 6 months (If any dose in the vaccination process is RotaTeq or unknown, the default is a 3-dose series.) | 6 weeks | 15 weeks | 8 months | Yes* |

| Canada | Rotarix: 2 doses at 2 & 4 months (≥4 weeks apart); RotaTeq: 3 doses at 2, 4, & 6 months (4-10 weeks interval) | 6 weeks | 15 weeks | 8 months | Yes |

| UK | Rotarix: 2 doses at 8 & 12 weeks (≥4 weeks interval) | 6 weeks | 15 weeks | 24 weeks | Yes |

| Finland | RotaTeq: 3 doses at 2, 3, & 5 months (≥4 weeks interval) | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 32 weeks/8 months | — |

| France | Rotarix: 2 doses at 2 & 3 months; RotaTeq: 3 doses at 2, 3, & 4 months | 6 weeks | — | Rotarix: 24 weeks RotaTeq: 32 weeks | Yes |

| Netherlands | Rotarix/RotaTeq: 2-3 doses as per vaccine guidelines | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 24 weeks | Yes |

| Norway | Rotarix: 2 doses at 6 weeks & 3 months | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 16 weeks | — |

Note: Can be safely co-administered with DTaP, Hib, hepatitis B, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines , among others, during the same visit. (Source: based on publicly available information).

Western Pacific and Southeast Asia

In the Western Pacific and Southeast Asia, only a few countries have included the RV vaccine in their NIPs, such as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Vietnam, and Thailand (see Table 6.2). Over ten countries, including China (with Hong Kong and Macau), have not yet included the vaccine into their NIPs.

Table 6.2 RV vaccine Recommended Schedules in Selected Western Pacific and Southeast Asian Countries

| Country | Vaccine Type & Schedule | Earliest Age | Latest Age for First Dose | Latest Age for Final Dose | Co-administration with Other Vaccines |

| Australia | Rotarix: 2 doses at 2 & 4 months (≥4 weeks interval) | 6 weeks | 14 weeks 6 days | 24 weeks 6 days | Yes |

| New Zealand | Rotarix: 2 doses at 6 weeks & 3 months (≥4 weeks interval. Infants who have had RV enteritis are still recommended to complete vaccination) | 6 weeks | 14 weeks 6 days | 24 weeks 6 days | Yes |

| Japan | Rotarix: 2 doses at 2 & 3 months; RotaTeq: 3 doses at 2, 3, & 4 months | 6 weeks | 14 weeks 6 days | Rotarix: 24 weeks RotaTeq: 32 weeks | — |

| Vietnam | Rotavin-M1: 2 doses, 2 months interval | 6 weeks | — | 6 months | — |

| Thailand | RotaTeq: 3 doses at 2, 4, & 6 months | — | — | — | — |

(Source: based on publicly available information)

Positive Impacts of RV vaccine Introduction

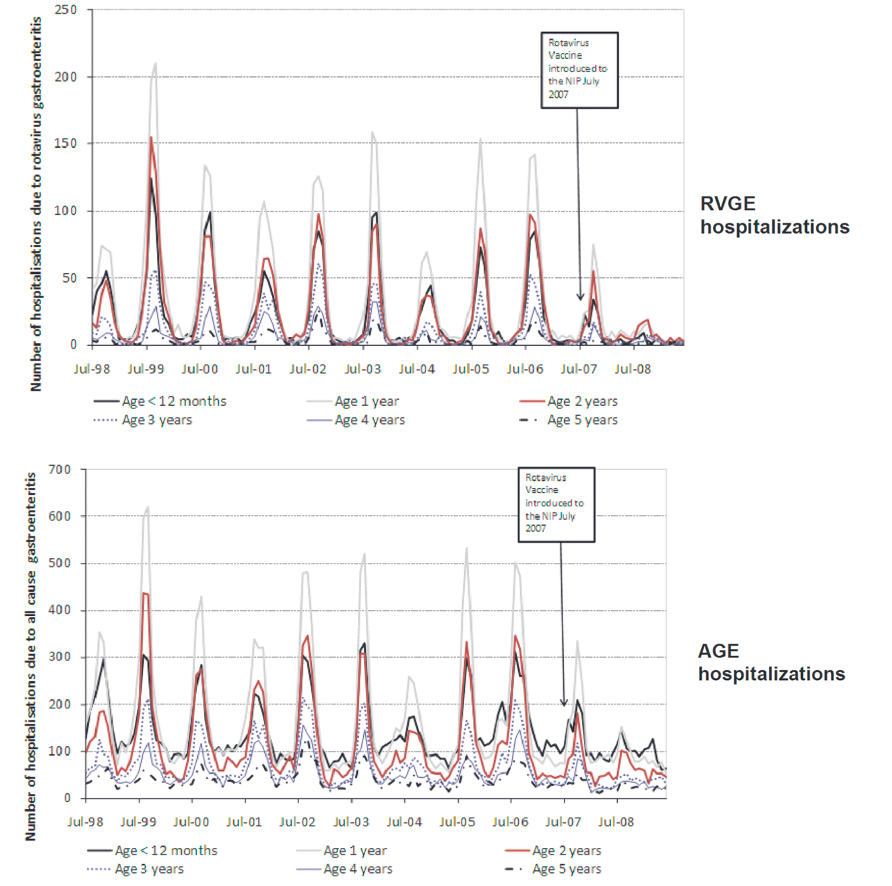

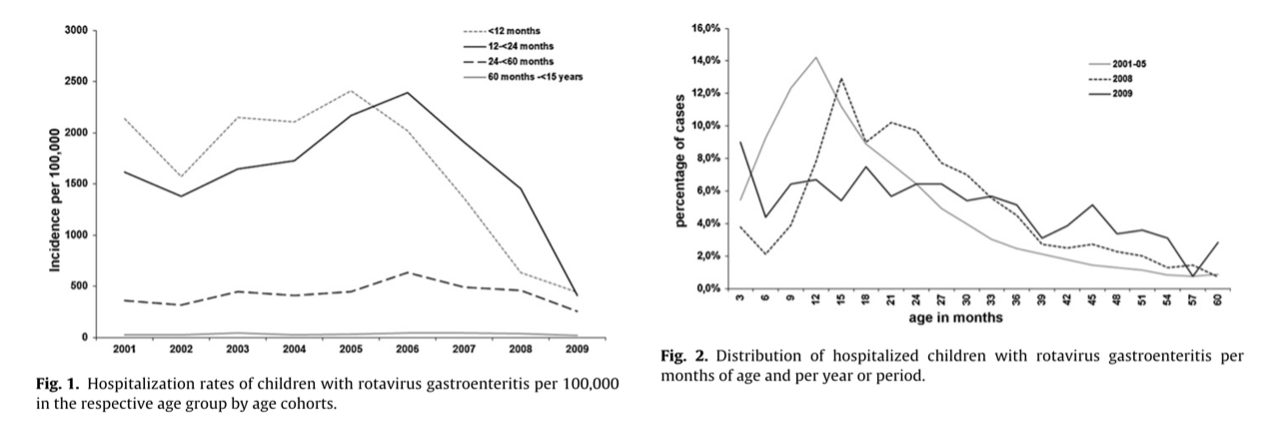

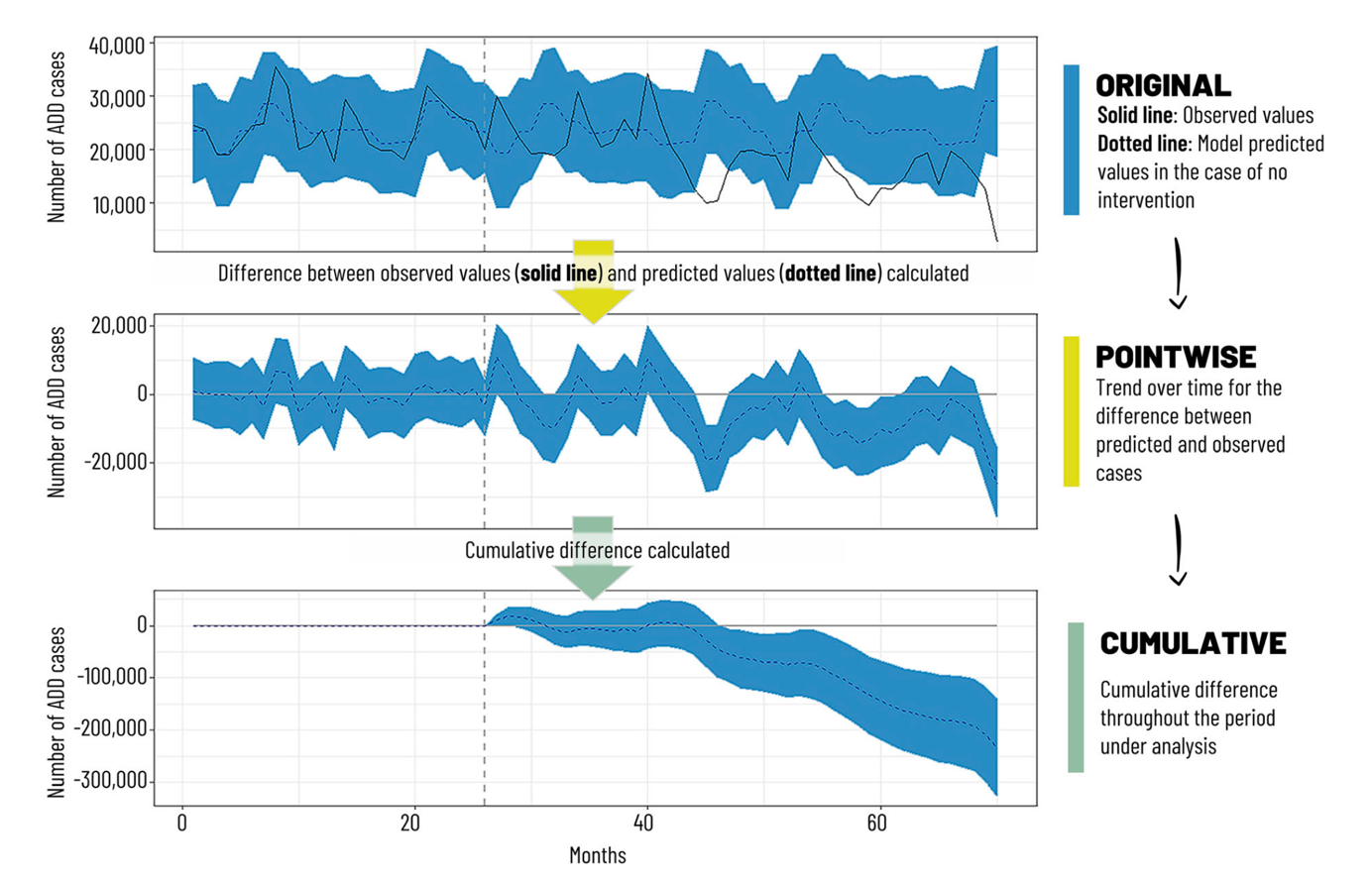

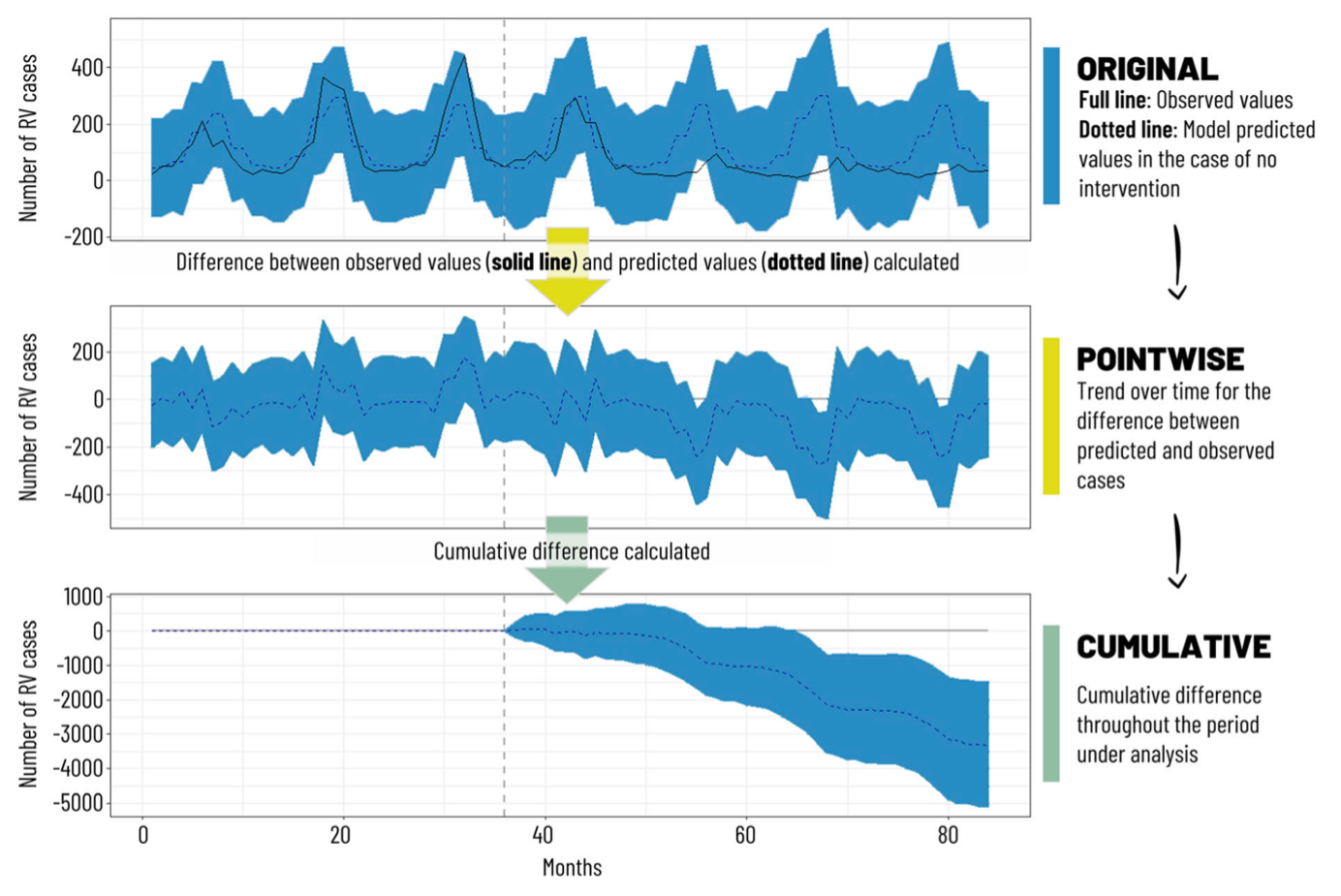

Countries that have included the RV vaccine in their NIPs have observed significant reductions in rotavirus-related hospitalizations among children under 5 years of age. In high-income countries like Australia (Figure 6.3), Austria (Figure 6.4), and the USA (Figure 6.5), hospitalizations decreased by 45% to 94%.5-10 Additionally, overall diarrhea-related hospitalizations in this age group decreased by 25% to 54%. Similar trends were observed in Latin America, with reductions in diarrhea-related hospitalizations ranging from 13% to 48%.11

Source:Pendleton, A. et al. Impact of RV vaccination in Australian children below 5 years of age. Hum Vaccin Immunother 9, 1617–1625 (2013).

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X11001769?via%3Dihub#fig0005

Source:Direct and Indirect Effects of Rotavirus Vaccination Upon Childhood Hospitalizations in 3 US Counties, 2006–2009. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/53/3/245/289062?login=true

Similar cases have been observed in Asian countries. During the pilot introduction of Rotarix in the Philippines, as vaccination coverage increased, diarrhea-related hospitalizations declined.12 By the third year after introduction, when the vaccine was available in pilot provinces and two-dose coverage reached 88%, the number of hospitalizations for diarrhea among children under 5 years old decreased by 63% compared to the average annual cases in the three years prior to vaccine introduction. However, in 2016, due to a six-month vaccine supply interruption, vaccination coverage dropped, and diarrhea-related hospitalization rates began to rise again.

In Thailand, Rotarix and RotaTeq were introduced in 2012 and incorporated into the NIP in 2020. A study comparing RVGE visit rates, hospitalization rates, and mortality before (2015-2019) and after (2020) the vaccine’s inclusion in the NIP found that in the year of introduction, infant diarrhea-related visit rates decreased by 17.8%, hospitalization rates by 2.9%, and mortality rates by 20%.13 In Latin America, Argentina introduced the RV vaccine into its NIP in January 2015. Over the following three years, acute diarrhea cases among children under 2 years old decreased by 22.1%, and hospitalizations due to RV infection decreased by 15.4%.11 The study also showed that reported RV infection cases among 2-year-olds and 1-year-olds decreased by 54.0% and 59.4%, respectively, while hospitalizations for RV infection in the same age groups decreased by 39.3% and 40.8%11.

Mexico included RV vaccine in its NIP revealed since 2006, with Rotarix (2 doses) was used from 2006 to 2011, followed by RotaTeq (3 doses) starting in 2011. A systematic review found that before 2006, 59% of gastroenteritis cases in children under 3 years old were caused by RV (2003 data). After vaccine introduction, Rotarix demonstrated 70%-100% efficacy against severe gastroenteritis and 70%-80% efficacy against all gastroenteritis. The vaccine significantly reduced diarrhea-related deaths (by 43%-55%), hospitalizations (with 42% efficacy against any gastroenteritis and 85% efficacy against severe gastroenteritis), and new cases (decreasing by 15.5%-46% from 2006 to 2017). The research concluded that the RV vaccine substantially reduced the diarrheal disease burden among children under 5 years old in Mexico and demonstrated favorable cost-effectiveness.14

Additionally, another systematic review found that RV vaccine can reduce antibiotic prescriptions, helping to mitigate antibiotic resistance.15 It is estimated that current RV vaccine coverage could prevent 13.6 million cases of antibiotic-treated diarrhea among children under 5 years old in LMICs.16 Since the introduction of the RV vaccine in India, antibiotic misuse due to RV infections among children under 5 years old has decreased by 21.8% (18.6%-25.1%).17 However, China still lacks research on the relationship between RV vaccine and antibiotic use.

Case Study: Vietnam’s RV vaccine Introduction

Vietnam’s introduction of the RV vaccine involved several stages: establishing a RV surveillance system, approving a domestic-made vaccine, conducting pilot programs in two provinces, monitoring safety and effectiveness, developing new vaccines, and transitioning from Gavi support to full domestic financing.

Before vaccine introduction, Vietnam established a hospital-based surveillance system for acute watery diarrhea in children under 5 years old. The RV positivity rate was around 50%.18 The domestic-made RV vaccine (Rotavin-M1 by POLYVAC), containing the G1P[8] strain, was approved in 2012. It is a liquid oral vaccine, with each dose being 2 mL and requiring storage at 2-8)°C.19

In December 2017, Rotavin-M1 was introduced in two provinces (Nam Dinh and TT Hue) as part of routine immunization. Safety monitoring at six hospitals found no association between vaccine use and intussusception.20 Coverage rates were 77% in Nam Dinh and 42% in TT Hue. In Nam Dinh, the RV positivity rate among children under 5 years old decreased by 40.6% (95% CI: 34.8%-45.8%) over three years, while no significant change was observed in TT Hue. Among children aged 6-23 months, the two-dose Rotavin-M1 vaccine demonstrated 57% efficacy in preventing hospitalizations due to moderate-to-severe diarrhea.21

Clinical trials of Vietnam’s second-generation RV vaccine (Rotavin) showed safety and efficacy comparable to Rotavin-M1, with no cases of intussusception or death. Rotavin was approved in January 2022 and included in the NIP in 2024.22 Given the high RV disease burden among children under 5 years old in Vietnam, the country’s capacity to produce the vaccine domestically, and post-marketing studies demonstrating the immunogenicity and safety of the locally produced vaccine, the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) proposed a plan to introduce the RV vaccine. This plan was developed after extensive consultations with stakeholders and government agencies, and it was approved by the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Finance, and the Prime Minister as part of the 2021-2025 NIP to ensure budget allocation for the vaccine’s introduction. In 2022, the Prime Minister approved the inclusion of the RV vaccine as a new vaccine in the NIP, and government funding was secured in 2023. Starting in 2024, 20% of the funding for purchasing the RV vaccine will come from Gavi (for Rotarix/Rotavin), while 80% will be covered by the Vietnamese central government (for domestic-made Rotavin). The costs of vaccine administration will be covered by Gavi. From 2025 onward, both vaccine procurement and administration costs will be fully funded by the Vietnamese central government.

Vietnam’s RV immunization program primarily targets infants under 1 year old, with two oral doses administered 2-3 months apart. The second-generation RV vaccine will be rolled out in phases, guided by principles of equity and sustainability. In 2024, the program will begin in remote mountainous areas, with the national budget covering 32 provinces and Gavi support covering 4 provinces. By 2025, the program will expand to 41 provinces, and by 2026, it will achieve nationwide coverage.23

Vietnam’s experience in introducing the RV vaccine into its NIP offers valuable lessons for other countries, including1) Using RV surveillance system data to objectively demonstrate the disease burden, 2) Prioritizing the development and use of domestic vaccines, supplemented by imported vaccines, 3) Conducting provincial pilot programs to gather evidence on coverage, safety, and effectiveness of local-made vaccines at scale, 4) Continuously advocating among stakeholders to overcome barriers to vaccine inclusion in the NIP, and 5) Adopting a phased introduction and multi-source financing strategy based on principles of equity and sustainability to gradually expand vaccine access nationwide.

Content Editor: Menglu Jiang, Ziqi Liu

Page Editor: Ziqi Liu

References

- VIEW-hub. Rotavirus vaccines. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://view-hub.org/vaccine/rota

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. (2022). Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction and Coverage. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-02/rota-brief1-introduction2022-1ax.pdf

- WHO Immunization Data portal – Detail Page. Immunization Data https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page

- Mandomando, I. et al. Lessons Learned and Future Perspectives for Rotavirus Vaccines Switch in the WHO African Region. Vaccines 11, 788 (2023).

- Ruiz-Palacios, G. M. et al. Safety and Efficacy of an Attenuated Vaccine against Severe Rotavirus Gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 354, 11–22 (2006).

- Paulke-Korinek, M. et al. Sustained low hospitalization rates after four years of rotavirus mass vaccination in Austria. Vaccine 31, 2686–2691 (2013).

- Paulke-Korinek, M. et al. Herd immunity after two years of the universal mass vaccination program in Austria. Vaccine 29, 2791–2796 (2011).

- Buttery, J. P. et al. Reduction in Rotavirus-associated Gastroenteritis in Australia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30, S25–S29 (2011).

- Pendleton, A. et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination in Australian children below 5 years. Hum Vaccin Immunother 9, 1617–1625 (2013).

- Payne, D. C. et al. Direct and Indirect Effects of Rotavirus Vaccination in US Counties. Clin Infect Dis 53, 245–253 (2011).

- Marti, S. G. et al. Rotavirus Vaccine Impact in Argentina. Infect Dis Ther 12, 513–526 (2023).

- Lopez, A. L. et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccine in the Philippines. Vaccine 36, 3308–3314 (2018).

- Charoenwat, B. et al. Rotavirus vaccine impact in Thailand. BMC Public Health 23, 2109 (2023).

- Guzman-Holst, A. et al. 15-year experience with rotavirus vaccination in Mexico: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 17, 3623–3637 (2021).

- Simhachalam Kutikuppala, L. V. et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on antibiotic use. World J Virol 13(2), 92586 (2024).

- Lewnard, J. A. et al. Childhood vaccines and antibiotic use in LMICs. Nature 581, 94–99 (2020).

- Gleason, A. et al. Rotavirus vaccine and antibiotic use in India: A simulation study. Vaccine 42(22), 126211 (2024).

- Huyen DTT et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in Vietnam. Vaccine 36(51), 7894–900 (2018).

- Skansberg, A. et al. Product review: ROTASIIL, ROTAVAC, and Rotavin-M1. Hum Vaccin Immunother 17, 1223–1234.

- Le, L. K. T. et al. Intussusception surveillance in Vietnam pilot provinces. Vaccines (Basel) 12, 170 (2024).

- Van Trang, N. et al. Impact and effectiveness of Rotavin-M1 in Vietnam. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 37, 100789 (2023).

- Thiem, V. D. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of rotavirus vaccines in Vietnam. Vaccine 39, 4463–4470 (2021).

- Duong Thi Hong. The immunization of RV vaccine in Vietnam. Presented at the 5th International Workshop on Rotavirus and Norovirus, Shanghai, May 8–9, 2024.