The Direct Effect

Reduction of Morbidity

Current surveillance data indicates that the incidence of serotype 3 invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in children has decreased following the introduction of PCV13. For example, in the United States, the incidence of serotype 3 IPD in children under 5 years of age dropped from 1.1 cases per 100,000 in 2010 to 0.25 cases per 100,000 in 2013 after the introduction of PCV131. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the number of serotypes 3 IPD cases in children under 5 decreased following the introduction of PCV13, with the incidence reported in 2013-2014 being 68% lower (95% CI: 6%-89%) than in 20082.

Another study reviewed the population effect of PCV introduction in English and Wales by comparing the incidence rate ratio against pre-PCV13 (2008/09-2009/10) and pre-PCV7 (2000/01-2005/06) baselines. By 2016/17, PCV7-type invasive pneumococcal disease incidence across all age groups had decreased by 97% compared with the pre-PCV7 period, whereas additional PCV13-type invasive pneumococcal disease decreased by 64% since the introduction of PCV13 3.

After Mongolia gradually included PCV13 in its routine infant immunization schedule in 2016, the incidence of pneumonia among children aged 2-59 months significantly decreased, and the overall carriage rate of PCV13 serotypes dropped by 44%4.

The United States was the first country in the world to incorporate the PCV vaccine into its national immunization program (PCV7 was introduced in 2000). A modeling study published in 2021 aimed to quantify the relationship between PCV vaccination and the incidence of IPD over 20 years since the introduction of PCV7 and PCV13 in the U.S. The results showed that the PCV vaccine prevented at least 282,000 cases of IPD, including approximately 16,000 cases of meningitis, about 172,000 cases of bacteremia, and around 55,000 cases of bacterial pneumonia. Additionally, PCV vaccination prevented 97 million visits for otitis media, 438,914 to 706,345 hospitalizations for pneumonia, and 2,780 deaths. The number of IPD cases dropped from 15,707 in 1997 to 1,382 in 2019, a 91% decrease. The annual number of otitis media visits decreased from 78 visits per 100 children before the introduction of PCV13 to 46 visits per 100 children after its introduction, a 41% reduction. Annual pneumonia hospitalizations decreased from 110,000-175,000 in 1997 to 37,000 in 2019, a reduction of 66%-79%. The study confirmed the significant benefits of PCV vaccination in preventing IPD in children5.

A systematic review published in 2019 on the effectiveness of PCV10/PCV13 in preventing IPD among children under five in Africa showed an overall reduction in IPD of 31.7% to 80.1% following the introduction of PCV. The decline in IPD caused by vaccine serotypes was even more pronounced, ranging from 35.0% to 92.0%, with a greater reduction (55.0% to 89.0%) observed in children under 24 months. However, the relative proportion of serotypes 1, 5, and 19A doubled after the vaccine rollout6.

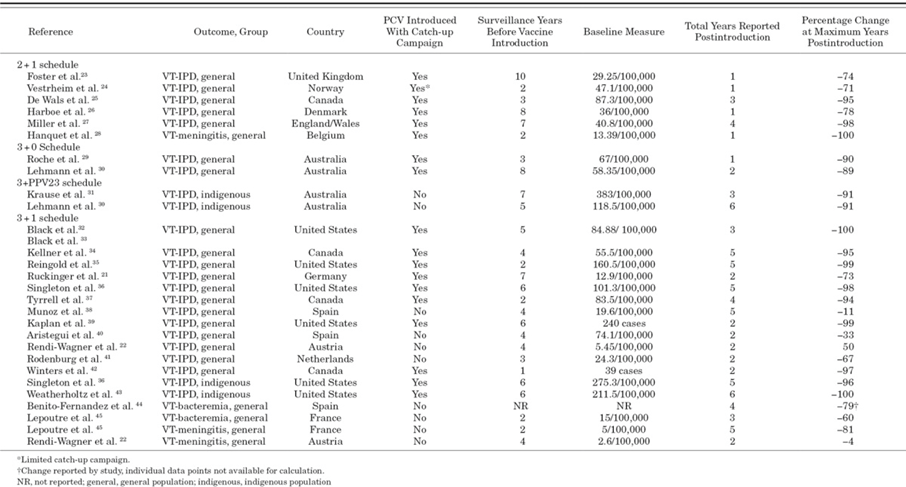

The varied effect due to the difference of vaccination schedule

In high-income countries that have included PCV in their national immunization programs, a 3-dose vaccination schedule can provide significant protection for children, with the specific schedule depending on the implementation context7. A 3-dose primary immunization schedule can offer good protection during the first year of a child’s life when the risk of disease is the highest. A booster dose (e.g., 3-dose primary series + 1 booster dose) can provide stronger long-term protection, particularly against serotype 18.

A systematic review in 2013 compared the effect of different dosing schedule of PCV on vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease (VT-IPD) among young children. The study supports the use of booster dose. In clinical trials, vaccine efficacy ranged from 65% to 71% with 3+0 schedule and 83% to 94% with 3+1 schedule. Surveillance data and case number showed the reduction of VT-IPD up to 100% with 2+1 or 3+1 schedules, and 90% reduction with 3+0 schedules. The reductions would happen as early as 1 year after PCV introduction9.

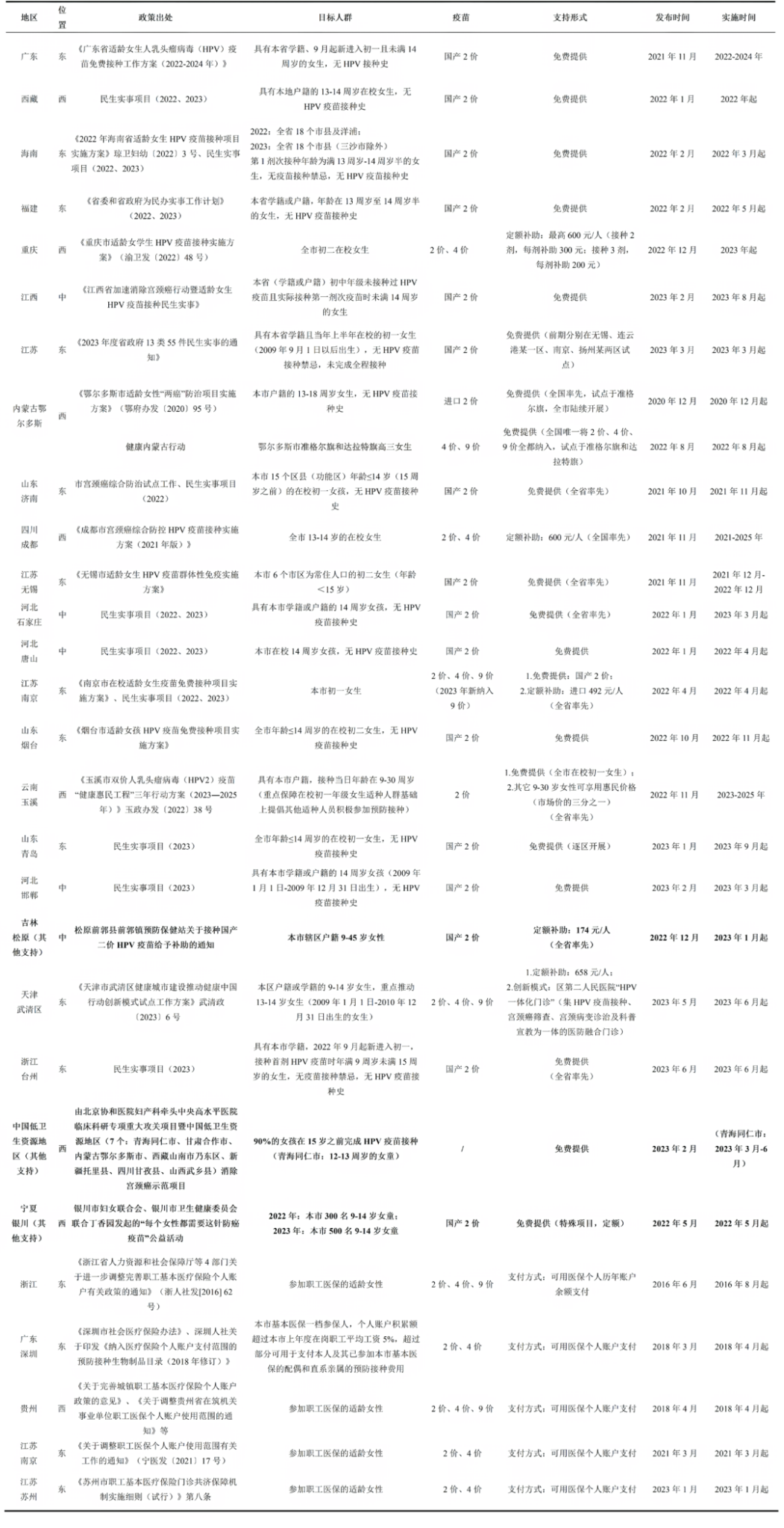

Table 1 Included Observational Studies Documenting Impact of PCV Introduction on VT-IPD, Meningitis or Bacteremia Among Young Children Before and After Vaccine Introduction, by PCV Dosing Schedule Setting

The Indirect Effect

Reduce the disease burden by herd protection

After the introduction of the PCV vaccine in most countries, there has been a decline in the incidence of IPD and pneumonia among adults. The effectiveness of herd immunity depends on the vaccination coverage rate and the duration since the introduction and implementation of PCV; the longer the vaccine has been in use, the more pronounced the indirect effects. Achieving strong indirect protection is only possible in populations with high vaccine coverage rates (above 70%-80%). Therefore, vaccination of children has a significant impact on the level of herd protection7.

Monitoring data from the United States shows that following the introduction of PCV7, there was a statistically significant decline in IPD incidence among adults, although the extent of the decline varied, with reductions up to 46.0%10. Most studies observed the significant decrease in IPD incidence among individuals aged 65 and older 7. This change is mainly associated with the duration since PCV was introduced. In countries where PCV7 was introduced later, there was also a general trend of IPD incidence decreasing, though the degree of reduction varied significantly. For example, three years after the introduction of PCV7, Denmark saw an 8.8% reduction in IPD incidence among those aged 65 and older in 201011; in Taiwan, China, seven years after PCV7 implementation, the overall adult IPD incidence rate dropped by as much as 70.0% by 201212.

Multiple studies have shown that the introduction of PCV10 and/or PCV13 also reduced IPD incidence, though the extent of reduction varied across different regions. For instance, in Ontario, Canada, the overall IPD incidence in adults aged 65 and older decreased by up to 61.12% following the introduction of PCV7, PCV10, and PCV1313. In contrast, in Israel, among individuals aged 18 and older, PCV7 and PCV13 only led to a 21.3% overall reduction in IPD incidence14. A study in Alaska, USA, found a significant decrease in IPD incidence among adults aged 18 to 44 after the introduction of PCV13, but no significant changes were observed in individuals aged 45 and older15.

Projected Timeline for Disease Burden Reduction

A 2017 study conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis about the indirect impact of PCV childhood immunization on the overall population’s incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD). The analysis included 242 studies and found that implementing a childhood PCV vaccination program could provide substantial protection to the entire population within ten years. When evaluating vaccination programs for the elderly, the indirect protective effect from the childhood PCV vaccination program should be taken into account16.

On average, it took 8.9 years (95% CI: 7.8-10.3 years) for the incidence of IPD caused by PCV7 serotypes to decrease by 90% across all age groups. For the six additional serotypes covered by PCV13, the estimated average time to achieve a 90% reduction in incidence was 9.5 years (6.1-16.6 years). The herd immunity effect will continue to accumulate over time16.

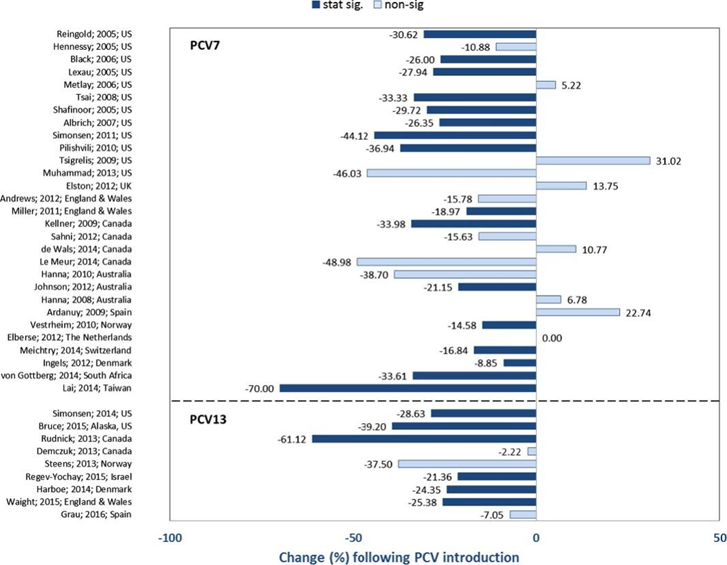

Table 2 Estimated Timeframe for IPD Reduction in Unvaccinated Age Groups Following PCV Introduction in Children

| Relative Risk(95% CI) | 50% reduction in program years (95% CI)* | 90% reduction in program years (95% CI)* | ||

| PCV7 serotypes | ||||

| Vaccine serotypes (all ages) | ||||

| 4 | 0.77 (0.72–0.84) | 2.8 (2.0–3.8) | 9.1 (7.1–12.2) | |

| 6B | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) | 2.7 (1.9–3.6) | 9.7 (7.7–12.8) | |

| 9V | 0.70 (0.66–0.77) | 2.5 (2.0–3.1) | 7.1 (5.9–8.8) | |

| 14 | 0.76 (0.69–0.85) | 1.9 (0.9–3.2) | 8.0 (5.9–12.6) | |

| 18C | 0.79 (0.73–0.86) | 4.1 (3.3–5.8) | 11.1 (8.8–17.0) | |

| 19F | 0.84 (0.80–0.90) | 5.1 (4.1–7.0) | 14.7 (11.8–22.2) | |

| 23F | 0.73 (0.68–0.79) | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 8.0 (6.6–10.0) | |

| Cross-reactive serotypes (all ages) | ||||

| 6A | 0.84 (0.78–0.89) | 6.4 (5.0–9.3) | 15.4 (11.8–23.1) | |

| 9N | 1.03 (0.95–1.13) | .. | .. | |

| 19A | 0.97 (0.84–1.15) | .. | .. | |

| All-age Group (All PCV7 serotypes) | ||||

| All ages | 0.79 (0.75–0.81) | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | 8.9 (7.8–10.3) | |

| <5 years | 0.62 (0.55–0.70) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 4.6 (3.9–6.0) | |

| 5–18 years | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 3.1 (1.9–4.9) | 10.8 (7.5–21.1) | |

| 19–49 years | 0.85 (0.76–0.96) | 1.9 (0.0–3.8) | 11.9 (8.0–30.0) | |

| 50–64 years | 0.78 (0.73–0.85) | 2.7 (2.0–3.4) | 9.1 (7.5–12.2) | |

| ≥65 years | 0.77 (0.75–0.80) | 2.6 (2.3–3.0) | 8.9 (7.9–10.3) | |

| Addition of PCV13 serotype | ||||

| Vaccine serotypes (all ages) | ||||

| 6A | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | 0.4 (0.0–30.0) | 11.9 (4.8–30.0) | |

| 1 | 0.76 (0.57–1.04) | 2.2 (0.6–30.0) | 7.8 (4.2–30.0) | |

| 3 | 1.03 (0.88–1.22) | 30.0 (6.8–30.0) | 30.0 (20.9–30.0) | |

| 5 | 0.59 (0.04–3.06) | 0.1 (0.0–30.0) | 5.7 (0.0–30.0) | |

| 7F | 0.83 (0.67–1.01) | 5.4 (2.9–30.0) | 14.1 (7.1–30.0) | |

| 19A | 0.74 (0.54–0.92) | 2.9 (2.0–10.5) | 7.6 (4.7–28.4) | |

| All-age Group (Addition of PCV13serotype) | ||||

| All groups | 0.75 (0.64–0.87) | 3.6 (2.5–6.1) | 9.5 (6.1–16.6) | |

| <5 years | 0.93 (0.30–2.64) | 0.0 (0.0–30.0) | 13.8 (0.0–30.0) | |

| 5–18 years | 0.78 (0.55–1.08) | 3.0 (0.0–30.0) | 9.5 (4.7–30.0) | |

| 19–49 years | 0.74 (0.56–0.99) | 3.1 (1.5–30.0) | 8.5 (4.6–30.0) | |

| 50–64 years | 0.77 (0.59–0.99) | 4.3 (2.4–30.0) | 10.4 (5.6–30.0) | |

| ≥65 years | 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | 4.1 (2.6–7.4) | 10.3 (6.4–20.7) | |

| IPD | ||||

| All-age Group(IPD) | ||||

| All groups | 0.99 (0.96–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| <5 years | 0.97 (0.91–1.01) | .. | .. | |

| 5–18 years | 0.97 (0.92–1.01) | .. | .. | |

| 19–49 years | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| 50–64 years | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| ≥65 years | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | .. | .. | |

| ..:Not estimated *The maximum cap is 30 years, with more than 30 years representing a 50 or 90 percent reduction that will never be reached. | ||||

Content Editor: Xiaotong Yang, Ziqi Liu

Page Editor: Ziqi Liu

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Invasive pneumococcal disease in the U.S., 2008–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/pneumo-04-matanock.pdf

- Waight PA, Andrews NJ, Ladhani SN, Sheppard CL, Slack MP, Miller E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:535–43.

- Ladhani SN, Collins S, Djennad A, et al. Rapid increase in non-vaccine serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales, 2000-17: a prospective national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Apr;18(4):441-451. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30052-5. Epub 2018 Jan 26. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Apr;18(4):376. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30074-4.

- von Mollendorf C, Ulziibayar M, Nguyen CD, Batsaikhan P, Suuri B, Luvsantseren D, Narangerel D, de Campo J, de Campo M, Tsolmon B, Demberelsuren S, Dunne EM, Satzke C, Mungun T, Mulholland EK. Effect of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine on Pneumonia Incidence Rates among Children 2-59 Months of Age, Mongolia, 2015-2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024 Mar;30(3):490-498. doi: 10.3201/eid3003.230864.

- Wasserman M, Chapman R, Lapidot R, et al. Twenty-Year Public Health Impact of 7- and 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines in US Children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(6):1627-1636.

- Ngocho JS, Magoma B, Olomi GA, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines against invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five years of age in Africa: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019 Feb 19;14(2): e0212295.

- Tsaban G, Ben-Shimol S. Indirect (herd) protection, following pneumococcal conjugated vaccines introduction: A systematic review of the literature. Vaccine. 2017 May 19;35(22):2882-2891.

- Klugman KP, Madhi SA, Adegbola RA, et al. Timing of serotype 1 pneumococcal disease suggests the need for evaluation of a booster dose. Vaccine. 2011;29:3372–3373.

- Conklin, L., Loo, J. D., Kirk, J., Fleming-Dutra, K. E., Deloria Knoll, M., Park, D. E., Goldblatt, D., O’Brien, K. L., & Whitney, C. G. (2014). Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease among young children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal, 33 Suppl 2(Suppl 2 Optimum Dosing of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine For Infants 0 A Landscape Analysis of Evidence Supportin g Different Schedules), S109–S118. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000000078

- Muhammad RD, Oza-Frank R, Zell et al. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among high-risk adults since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for children. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Mar;56(5):e59-67. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis971.

- Hennessy TW, Singleton RJ, Bulkow LR, et al. Impact of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive disease, antimicrobial resistance and colonization in Alaska Natives: progress towards elimination of a health disparity. Vaccine. 2005 Dec 1;23(48-49):5464-73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.100.

- Lai CC, Lin SH, Liao CH, et al. Decline in the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease at a medical center in Taiwan, 2000-2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Feb 11;14:76. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-76.

- Rudnick W, Liu Z, Shigayeva A, et al. Pneumococcal vaccination programs and the burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in Ontario, Canada, 1995-2011. Vaccine. 2013 Dec 2;31(49):5863-71. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.049.

- Regev-Yochay G, Paran Y, Bishara J, et al. Early impact of PCV7/PCV13 sequential introduction to the national pediatric immunization plan, on adult invasive pneumococcal disease: A nationwide surveillance study. Vaccine. 2015 Feb 25;33(9):1135-42. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.030.

- Bruce MG, Singleton R, Bulkow L, et al. Impact of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (pcv13) on invasive pneumococcal disease and carriage in Alaska. Vaccine. 2015 11;33(38):4813-9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.080.

- Shiri T, Datta S, Madan J, et al. Indirect effects of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 Jan;5(1):e51-e59.