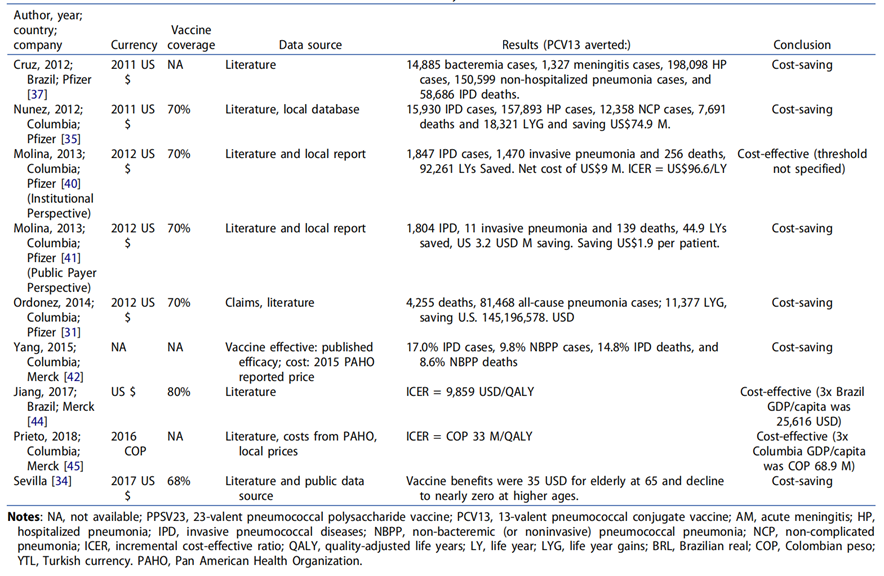

The cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccines varies from country to country. Several studies have found that the parameters that most influence the cost-effectiveness of vaccines are vaccine efficacy, coverage, price, disease incidence rate, mortality, treatment costs for the pneumococcal diseases, herd immunity effects and serotype replacement. In addition, the research hypothesis, model structure, disease burden, and sponsorship also could affect the outcomes of economic evaluation.

A systematic review evaluated health utility values, medical resource use, and economic costs associated with pneumococcal diseases, including the cost-effectiveness of various interventions such as vaccination programs for both adults and children.1 The review included 383 studies, 140 of which focused on the economic evaluations of pneumococcal immunization’s cost-effectiveness. The findings indicated that immunization programs in most countries are cost-effective, aligning with the objective of summarizing evidence which are critical for informing future health economic analyses.1

The cost-effectiveness of adult pneumococcal vaccination

In the a forementioned review, cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination in adults has been evaluated, with 50 papers focusing on economic assessments of PCV vaccination. Among these papers, 25 were conducted in Europe, 17 in the United States, with two each in Colombia and Brazil, and single studies in Canada, Japan, Mainland China, and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.1

1) Cost-effectiveness compared with no vaccination

36 studies assessed the impact of vaccination with PPV23 versus no vaccination among adults. Economic evaluations ranged from cost-saving to an average Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) of $375,355 per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) gained based on time varying from one year to lifetime.1 9 studies analyzed PCV13 vaccination’s impacts in adults population, with results ranging from overall cost-saving to an average ICER of $325,021 per QALY gained.1 In Spain, Colombia, and Finland, PCV13 vaccination in adults over 50 was proved be cost-saving.1 2 studies in Italy and the United States evaluated the cost-effectiveness of PCV13 and PPV23 combination or sequential vaccination* compared with no vaccination in adults over time spans ranging from 5 to 50 years, with mean ICERs ranging from $29,607 to $38,384 per QALY gained. 2,3

2) Cost-effectiveness of different vaccination strategies

A 15-year U.S. study among immunocompromised adults aged 19 to 64 found that a single dose of PCV13 was the more cost-effective strategy.4 Another U.S. study indicated that replacing the original PPV23 with PCV13 for adults aged 65 and older, as well as younger populations with multiple comorbidities, was more cost-effective.5 Compared to this replacement strategy, routine PCV13 vaccination at ages 50 and 65 cost $45,100 per QALY while an additional PPV23 vaccination at age 75 yielded 0.00002 QALYs at a cost of $496,000 per QALY.5 A French study evaluated the public health and budget impact of different vaccination strategies (i.e., PPV23 for immunocompetent individuals and PCV13 for immunocompromised individuals; or PCV13 only) in high-risk adult populations suggesting that in the high-risk population group, vaccinating immunocompetent individuals with PPV23 and immunocompromised with PCV13 might provide better protection.6 However, considering the additional budget required for an additional PCV13-only strategy, PPV23 remains the preferred strategy for immunocompetent individuals.6

3) Cost-effectiveness of Different Age Groups’ PPV23 vaccination

5 studies conducted in the United States, Japan, and Brazil evaluated the effects of PPV23 in different age groups of adults. Among them, a study from the United States indicated that the vaccination strategy targeting the 50-year-old population had an advantage over the strategy targeting individuals under 65 with multiple chronic diseases in terms of health economic assessment outcomes. Compared to vaccinating only individuals aged 65, the vaccination strategy for both 65- and 80-year-old populations was more advantageous; vaccinating three age groups (50, 65, and 80 years old) was more advantageous than vaccinating two age groups (50 and 65 years old).4,7 Compared to vaccinating the entire population with influenza vaccine and administering PPV23 to adults with chronic diseases and their complications, vaccinating adults aged 50 and above with only PPV23 was more economically advantageous.8 Studies from Japan showed that, compared to vaccinating only individuals aged 65 with PPV23, vaccinating both 65- and 80-year-old individuals with the vaccine was more economically advantageous.9 Research from Brazil demonstrated that universal vaccination of PPV23 for individuals over 60 years old is a highly cost-effective strategy, with the ICER values ranging from $970 to $1,392 per additional life-year gained(LYG).

The cost-effectiveness of children pneumococcal vaccination

A total of 90 studies on the cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination in children were included in the aforementioned review.1 39 studies were conducted in Europe, 19 in Asia, 13 in North America, 24 in South America, three in Australia, and seven in Africa, with some studies covering multiple countries.

1) Cost-effectiveness compared with no vaccination

PCV7 vaccination versus no vaccination: In Finland, PCV7 was considered not cost-effective.10 The ICER was $143 per Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) averted in resource-limited settings; in Singapore, it was $47,392. In Canada, the ICER ranged from $456 to $266,333 per QALY averted.11 In Germany, the ICER was $242 per LYG.12

PCV10 vaccination versus no vaccination: 23 countries’ studies analyzed the cost-effectiveness of PCV10 vaccination compared to no vaccination, with studies from Canada, Colombia, and Chile all showing that PCV10 vaccination is cost-effective.1 The average ICER ranged from $65 per QALY averted in Kenya to $70,066 in Croatia1.Additionally, studies indicated that PCV10 has moderate cost-effectiveness in Singapore and is not cost-effective in Thailand.13,14

PCV13 vaccination versus no vaccination: 22 countries conducted economic evaluations of PCV13 vaccination in children. The ICER ranged from $51 per QALY averted in Kenya to $71,371 in Croatia; from $3,147 per QALY averted in the Philippines to $288,222 in the United Kingdom.1 Studies from China and Thailand showed that introducing PCV13 into the NIP is not cost-effective.14,15

2) Cost-effectiveness of different valences of PCV vaccines

18 countries’ studies compared the cost-effectiveness of PCV10 and PCV13 vaccinations. Studies indicated that PCV13 is more cost-effective in Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Colombia, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, and Malaysia, while analyses in Peru, Norway, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, and Turkey showed that PCV10 is more cost-effective.1

A review study summarized the economic evaluations of three types of pneumococcal vaccines for children (PCV7, PCV10, PCV13) from 2006 to 2014, including 63 documents.16 The study concluded that, based on the review, PCV13 and PCV10 may be more cost-effective than PCV7. However, due to uncertainties regarding serotype replacement and herd effects, serotype cross-protection, and protection against incidental acute otitis media (AOM) caused by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), the evidence for which vaccine is more cost-effective is not clear.16

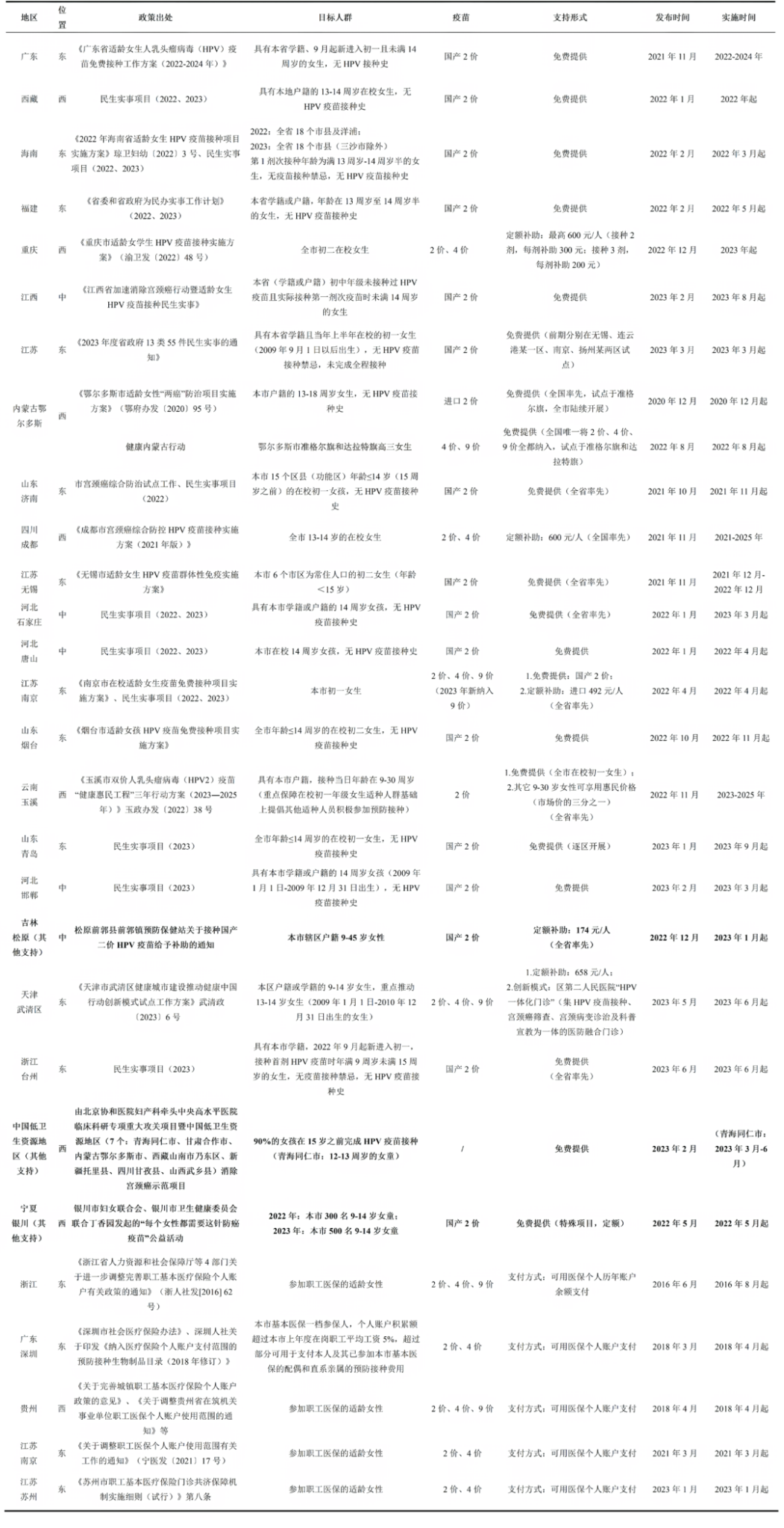

Cost-effectiveness of children and adult vaccination in LMICs

The Cost-effectiveness in children and adults in low- and middle-income countries is influenced by the significant price variability of PCVs. Achieving higher cost-effectiveness is contingent upon reducing vaccine prices. A model study estimated the total global cost of PCV vaccination to be $15.5 billion. In North America, the average cost per fully vaccinated child is $541, with the total vaccination cost in Europe being higher at $599, Asia at $104, and Africa at $52. Comparatively, Africa incurs fewer costs due to funding from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi). The 71 countries receiving Gavi support account for 83% of the deaths preventable by PCV13, yet their costs represent only 18% of the global vaccination expenses.17

Pneumococcal vaccination for infants and young children in low- and middle-income countries is cost-effective. A study including 72 developing countries estimated that PCV vaccination could prevent 262,000 deaths annually among children aged 3 to 29 months, thereby averting 8.34 million DALYs annually. If every child were vaccinated, up to 407,000 deaths could be prevented annually. With an international vaccine price of $5 per dose, the net cost of vaccination would be $838 million, with a cost-effectiveness $100 per DALY averted. Based on each country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and the cost per DALY averted, it is projected that 68 out of the 72 countries included in the study would find vaccination at this price highly cost-effective.18

A systematic study on the cost-effectiveness of PCV vaccination for adults aged 50 and above in low- and middle-income countries indicates that vaccinating the elderly with either PPV23 or PCV13 is economically advantageous, with most cases resulting in cost savings and high cost-effectiveness.18

Table 1: Comparing cost-effectiveness of PCV13 vaccination versus no vaccination for adults aged 50 and above in LMICs

The cost-effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccination for children and adults in China

A systematic review of the economic evaluation of different immunization strategies for PCV in China showed that out of 13 studies included, 10 indicated that incorporating PCV into national or regional immunization programs is economically beneficial, preventing a substantial number of pneumococcal-related deaths in children under 5 and generating significant societal costs savings.19 Some studies also suggest that incorporating PPV23 into the immunization program has a higher cost-effectiveness than incorporating PCV.19 Another study showed that, assuming a base price of $25 per dose in the NIP, introducing PCV13 nationwide is cost-effective, with an ICER of $5,222 per additional QALY gained. Compared to providing PCV13 solely through private market, incorporating PCV13 into the childhood immunization schedule is cost-effective in 17 out of 31 provinces in the country, with 4 provinces achieving cost savings.20

For the adult pneumococcal vaccination, studies conducted in some cities show that vaccinating the elderly with PPV23 is cost-effective. A modeling study conducted among elderly people over 60 years old in Shanghai found that PPV23 vaccination could reduce the cumulative incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), and hospitalization by 3.57%, 0.02%, and 1.06%, respectively, with an ICER of $16,700 per QALY, and the return on investment for the PPV23 strategy approaching 90%.21 A cost-effectiveness analysis of PPV23 vaccination in the elderly in Beijing showed that the higher the vaccine price, the lower the benefit-cost ratio (BCR), and that a better cost-effectiveness can be achieved by reducing the vaccine price.22 Furthermore, the analysis indicated that a favorable benefit-cost ratio (BCR) could be achieved as long as the disease incidence remains above 3.87 cases per 100 person-years.22

A study comparing different pneumococcal vaccination strategies among individuals over 65 years old showed that compared to no vaccination, the ICERs for PPV23, PCV13, and sequential PCV13-PPV23 vaccination strategies were $10,776.7/QALY, $9,193.2/QALY, and $15,080.0/QALY.23 Based on a one-time national per capita GDP threshold, PCV13 alone emerged as the most cost-effective option and the only strategy meeting the national per capita GDP threshold for cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, the cost of the PPV23 vaccination strategy is the lowest, while the sequential PCV13-PPV23 vaccination strategy has the most significant impact on reducing the burden of pneumococcal disease.23

Content Editor: Menglu Jiang, Ziqi Liu

Page Editor: Ziqi Liu

Glossary

Sequential Vaccination refers to the administration of vaccines with different technological platforms at specified intervals. In the context of this article, sequential vaccination refers to the initial administration of one type of pneumococcal vaccine (e.g., PCV13) followed by another type of pneumococcal vaccine (e.g., PPV23). This vaccination strategy aims to provide more comprehensive protection by leveraging the advantages of different vaccines to cover a broader range of pneumococcal serotypes, thereby enhancing overall immunogenicity.

References

1. Shiri, T., Khan, K., Keaney, K., Mukherjee, G., McCarthy, N. D., & Petrou, S. (2019). Pneumococcal disease: a systematic review of health utilities, resource use, costs, and economic evaluations of interventions. Value in Health, 22(11), 1329-1344.

2. S. Boccalini, A. Bechini, M. Levi, et al. Cost-effectiveness of new adult pneumococcal vaccination strategies in Italy Hum Vaccin Immunother, 9 (2013), pp. 699-706

3. J. Chen, M.A. O’Brien, H.K. Yang, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccines for adults in the United States Adv Ther, 31 (2014), pp. 392-409

4. K.J. Smith, M.P. Nowalk, M. Raymund, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in immunocompromised adults. Vaccine, 31 (2013), pp. 3950-3956

5. K.J. Smith, A.R. Wateska, M.P. Nowalk, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adult vaccination strategies using pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. JAMA, 307 (2012), pp. 804-812

6. Y. Jiang, F. Gervais, A. Gauthier, et al. A comparative public health and budget impact analysis of pneumococcal vaccines: the French case. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 11 (2015), pp. 2188-2197

7. K.J. Smith, R.K. Zimmerman, C.J.Lin, et al. Alternative strategies for adult pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination: a cost-effectiveness analysis Vaccine, 26 (2008), pp. 1420-1431

8. K.J. Smith, B.Y. Lee, M.P. Nowalk, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dual influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in 50-year-olds Vaccine, 28 (2010), pp. 7620-7625

9. S.L. Hoshi, M. Kondo, I. Okubo Economic evaluation of immunisation programme of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and the inclusion of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the list for single-dose subsidy to the elderly in Japan PLoS One, 10 (2015), p. e0139140

10. H. Salo, H. Sintonen, J.P. Nuorti, et al. Economic evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in Finland Scand J Infect Dis, 37 (2005), pp. 821-832

11. B. Poirier, P. De Wals, G. Petit, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a 3-dose pneumococcal conjugate vaccine program in the province of Quebec, Canada Vaccine, 27 (2009), pp. 7105-7109

12. A. Lloyd, N. Patel, D.A. Scott, et al. Cost-effectiveness of heptavalent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (Prevenar) in Germany: considering a high-risk population and herd immunity effects Eur J Health Econ, 9 (2008), pp. 7-15

13. K.R. Tyo, M.M. Rosen, W. Zeng, et al. Cost-effectiveness of conjugate pneumococcal vaccination in Singapore: comparing estimates for 7-valent, 10-valent, and 13-valent vaccines Vaccine, 29 (2011), pp. 6686-6894

14. W. Kulpeng, P. Leelahavarong, W. Rattanavipapong, et al. Cost-utility analysis of 10- and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: protection at what price in the Thai context? Vaccine, 31 (2013), pp. 2839-2847

15. X. Mo, R. Gai Tobe, X. Liu, et al. Cost-effectiveness and health benefits of pediatric 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and forecasting 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in China Pediatr Infect Dis J, 35 (2016), pp. e353-e361

16. Wu DB, Chaiyakunapruk N, Chong HY, Beutels P. Choosing between 7-, 10- and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in childhood: a review of economic evaluations (2006-2014). Vaccine. 2015 Mar 30;33(14):1633-58. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.081. Epub 2015 Feb 11. PMID: 25681663.

17. Chen C, Cervero Liceras F, Flasche S, Sidharta S, Yoong J, Sundaram N, Jit M. Effect and cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: a global modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Jan;7(1):e58-e67. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30422-4.

18. Saokaew, S., Rayanakorn, A., Wu, D. B.-C., & Chaiyakunapruk, N. (2016). Cost Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccination in Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics, 34(12), 1211-1225.

19. Zhang, H., Lai, X., Lü, Y., Feng, H., Wang, J., Guo, J., Zhang, H., & Fang, H. (2022). A systematic review of economic evaluations on different pneumococcal conjugate vaccine immunization strategies in China. Chinese Health Economics, 41(2), 9–14

20. Lai, X., Garcia, C., Wu, D., Knoll, M. D., Zhang, H., Xu, T., Jing, R., Yin, Z., Wahl, B., & Fang, H. (2023). Estimating national, regional and provincial cost-effectiveness of introducing childhood 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in China: A modelling analysis. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, 32, 100666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100666

21. Sun X, Tang Y, Ma X, et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Program for the Elderly Aged 60 Years or Older in Shanghai, China. Front Public Health. 2021 May 24; 9:647725.

22. Liu, J., Ji, W., & Wu, J. (2011). Cost-effectiveness analysis of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination among the elderly in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 27(2), 191–193.

23. Guo, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, H., Lai, X., Wang, J., Feng, H., & Fang, H. (2023). Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccines among adults aged 65 years and older in China: A comparative study. Vaccine, 41(3), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.12.004