Introduction to Rotavirus

Rotavirus Types and Human Transmission Sources

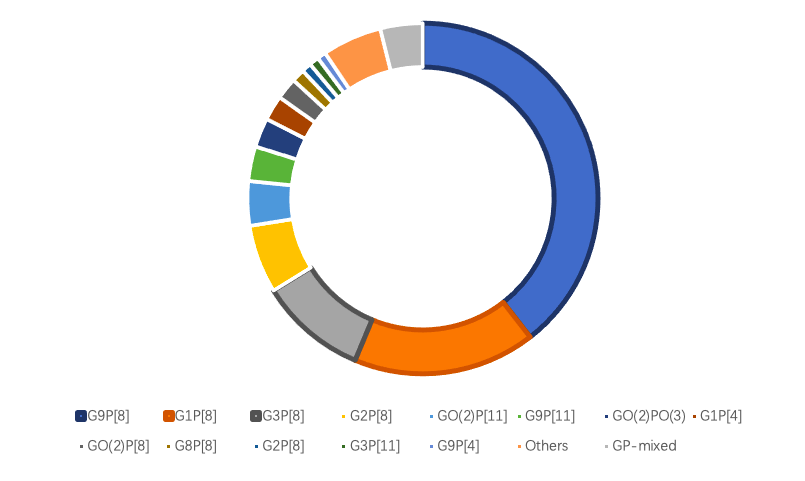

Rotavirus (RV) is one of the leading cause of rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) in children under the age of five worldwide1,2. Rotavirus consists of multiple types, with Group A rotavirus (RVA) being the most common, accounting for over 95% of human infections³. Due to differences in the outer capsid proteins, rotavirus exhibits genetic diversity. In humans, at least 11 different G genotypes and 11 different P genotypes exist, and various combinations of these genotypes distinguish the virus strains4-8. The predominant RV genotypes globally include G9P[8], G8P[8], G3P[8], G1P[8], G2P[4], and G4P[8] 4.

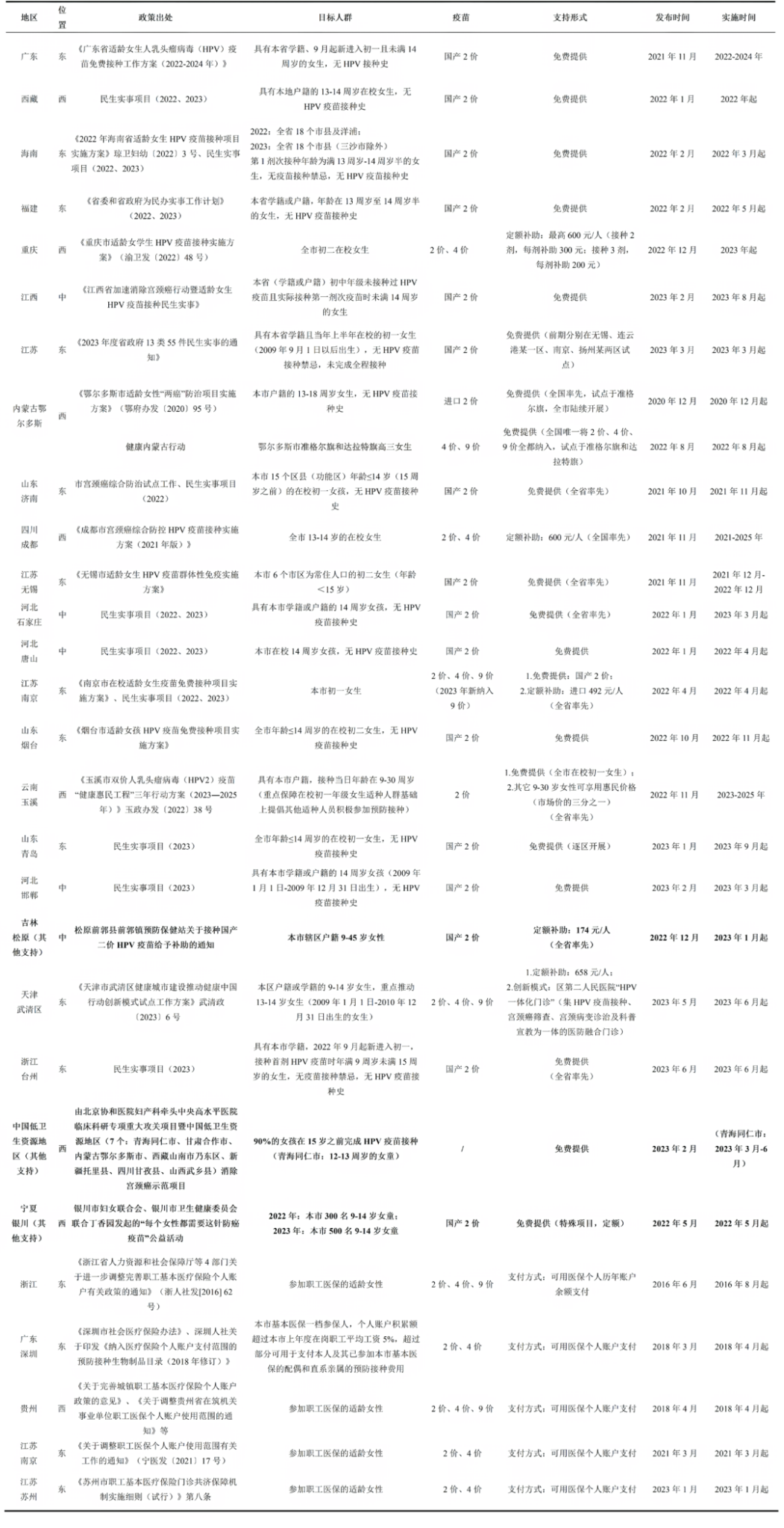

Among human populations, asymptomatic individuals infected with rotavirus and those suffering from RVGE are the primary sources of transmission. A systematic review analyzing 361 datasets on rotavirus genotypes among children under the age of five from 2005 to 2023 found that within one to two years of vaccine introduction, the prevalence of the non-vaccine genotype G2P[4] significantly increased in vaccinated regions. However, this trend was not observed in the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) region6.

(“None” indicates that the rotavirus vaccine had not yet been introduced at the time of genotype data collection, while “After” indicates that the vaccine had been introduced. Abbreviations: AFRO – African Region; AMRO – American Region; EMRO – Eastern Mediterranean Region; EURO – European Region; SEARO – Southeast Asian Region; WPRO – Western Pacific Region.)

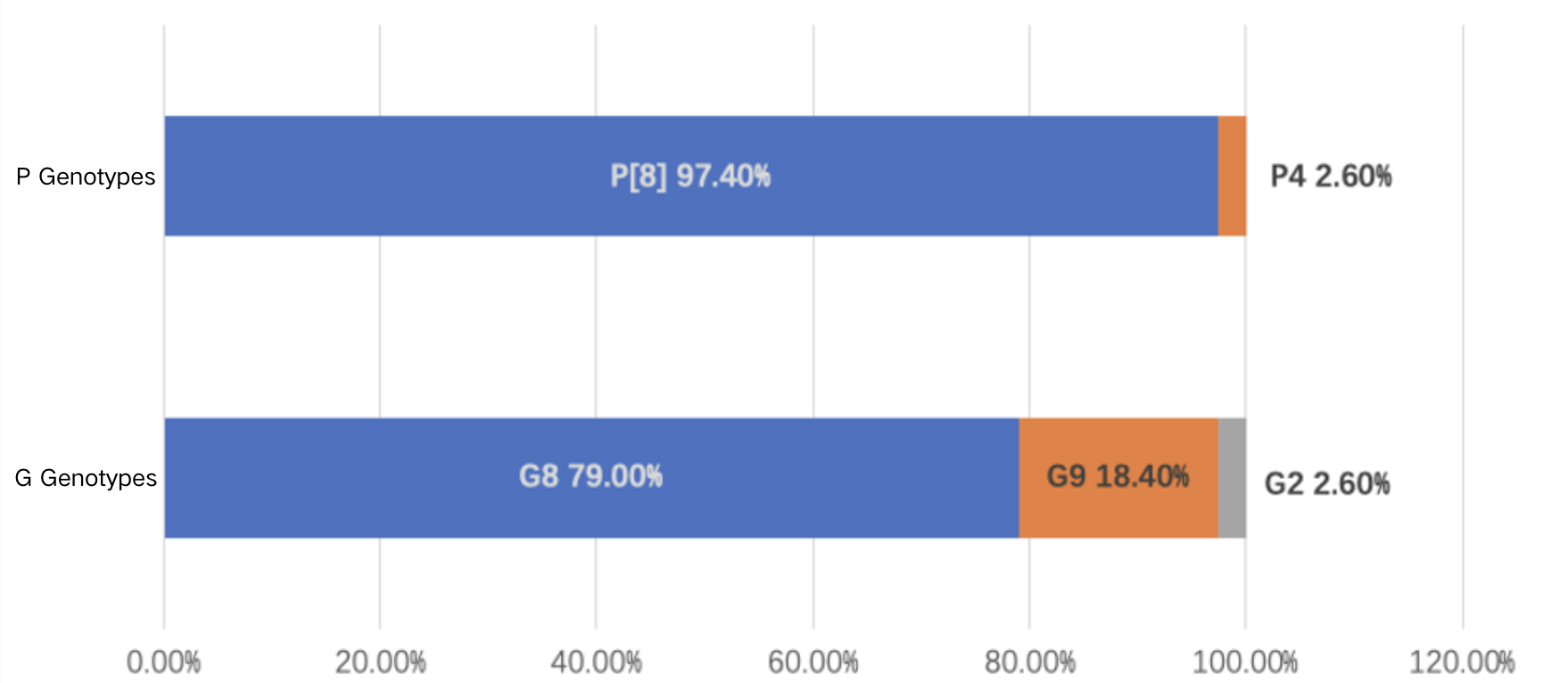

Between 2009 and 2014, Group A rotavirus was the most prevalent serotype among rotavirus diarrhea cases in children under five years old, accounting for an average of 95.1% (4,404 cases) of all strains, while Groups B and C accounted for only 2.8% (129 cases) and 2.1% (98 cases), respectively³. The dominant genotype of Group A rotavirus in China has gradually shifted over time. Initially, the predominant G genotypes were G3 and G1, but later G9 became the dominant strain. The P genotype has consistently been dominated by P[8]. As a result, the predominant genotype combination shifted from G3P[8] to G9P[8], aligning with global trends in circulating strains⁶.

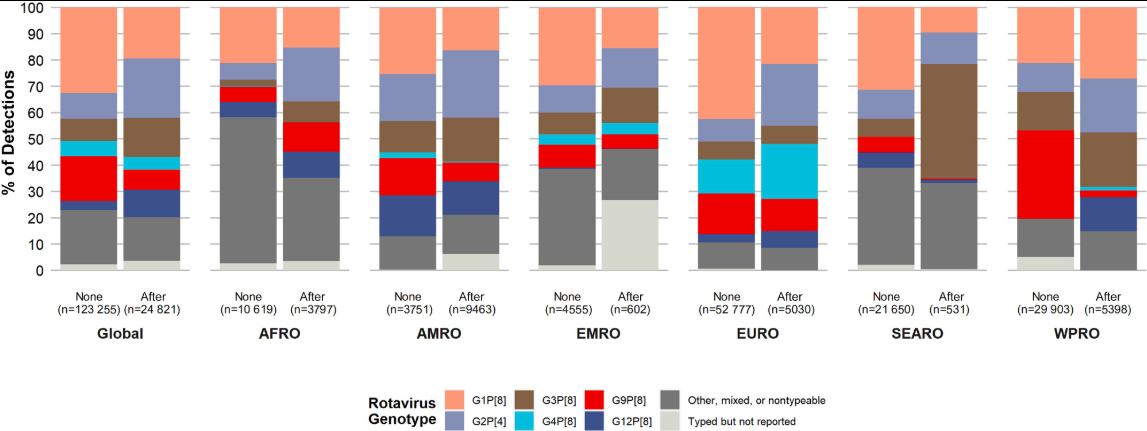

Domestic G3, G9, and P[8] rotavirus strains have been found to be homologous to strains from Russia and Belgium, with evolutionary trends similar to those observed in Russia⁷⁸. During the 2021–2022 rotavirus season, observations in Shanghai indicated that the most common G genotype was G8, followed by G9, while the most prevalent P genotype was P[8], accounting for 97.4% of cases. G8P[8] had become the most common circulating strain²⁶. Another study found that the dominant Group A rotavirus genotype in Beijing also shifted from G9‐VP[8]‐III in 2019–2021 to G8‐VP[8]‐III in 2022. Furthermore, the P[8] sequence of the G8‐VP[8]‐III strain formed a new branch. Researchers speculate that this phenomenen may be associated with rotavirus vaccine administration⁹.

Data Source: Ma W, Wei Z, Guo J, et al. Effectiveness of Pentavalent Rotavirus Vaccine in Shanghai, China: A Test-Negative Design Study. J Pediatr. 2023;259:113461. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113461

Data Source: Expert Consensus on Immunization Prevention of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis in Children (2024 Edition)

Data Source: Expert Consensus on Immunization Prevention of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis in Children (2024 Edition)

Main Transmission Routes

The spread of RVGE requires three fundamental elements: a source of infection, a mode of transmission, and a susceptible population. If any of these elements are missing, new rotavirus infections cannot occur. Various natural and social factors can influence these three elements and their interactions, thereby affecting disease transmission and its prevalence.³

Rotavirus is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route, meaning infection occurs through contact with food, water, objects, or surfaces contaminated with the virus.¹⁰ Rotavirus may also spread through respiratory transmission, although this is less common.¹¹ Rotavirus infection typically has an acute onset, with major symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever.¹⁰ ¹² Severe rotavirus infection can lead to electrolyte imbalances, acid-base disturbances, and even death.

Susceptible Populations

Children under five years old, especially infants and toddlers aged 3 to 35 months, are at the highest risk of rotavirus infection, with non-daycare children being the most affected cases.¹³ ¹⁴ While most adults have acquired some immunity to rotavirus, elderly individuals, immunocompromised individuals, and those with specific genetic factors remain susceptible to infection.¹⁵ ¹⁶

Epidemiological Characteristics

Seasonal and Regional Distribution

(1) Global Seasonal and Regional Distribution of Rotavirus

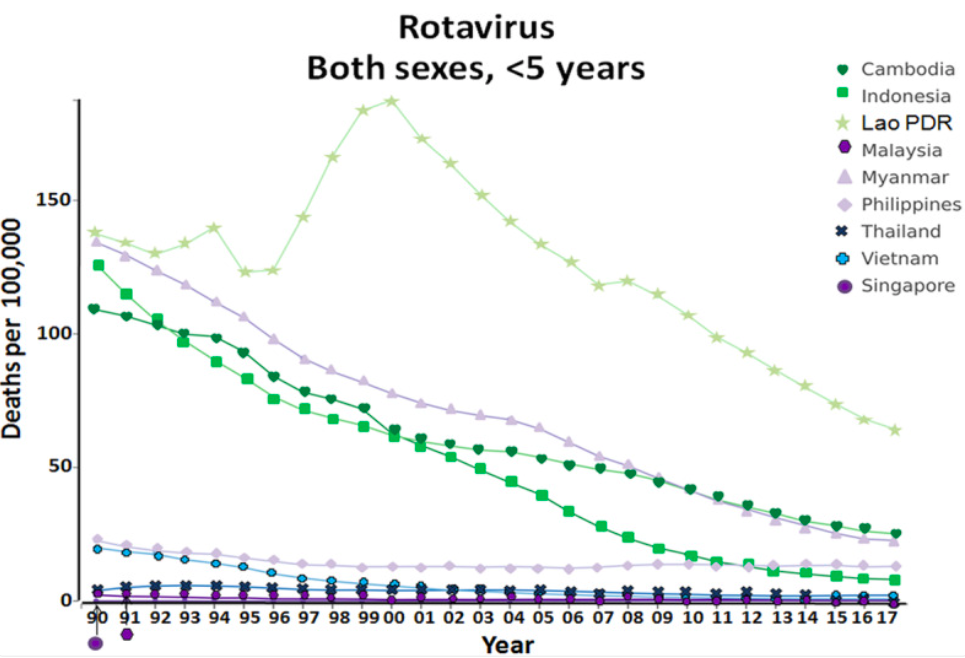

RVGE occurs year-round, with clear seasonal peaks in most regions worldwide, though the timing of peak incidence varies across different geographical areas.³

Before the widespread introduction of rotavirus vaccines, RVGE outbreaks in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere typically peaked during autumn and winter (October to February) and early spring (March to May). In the Southern Hemisphere, peak incidence generally occurred from May to October, corresponding to the winter season in that region. In tropical regions, RVGE persists year-round, with fluctuations in incidence each month. However, these fluctuations are less pronounced compared to the distinct seasonal patterns observed in temperate regions.¹⁷

Rotavirus can be detected throughout the year in Africa, Asia, and South America. In contrast, regions such as Europe, North America, and Oceania exhibit more distinct seasonal patterns. Following the introduction of rotavirus vaccines, the peak season for RVGE in these regions has shifted, with a delayed onset, a shorter duration of outbreaks, and a reduced peak intensity.¹⁸ ¹⁹

The coverage rate of rotavirus vaccination significantly influences the seasonal distribution of the disease. For example, two years after the large-scale introduction of rotavirus vaccination in Western European countries, the start and/or end of the RVGE season, as well as the peak incidence period, were delayed by approximately 4 to 7 weeks.²⁰

Source: Lestari, F. B., Vongpunsawad, S., Wanlapakorn, N., & Poovorawan, Y. Rotavirus infection in children in Southeast Asia 2008–2018: disease burden, genotype distribution, seasonality, and vaccination. J Biomed Sci 27, 66 (2020).

(2) Seasonal and Regional Distribution of Rotavirus in China

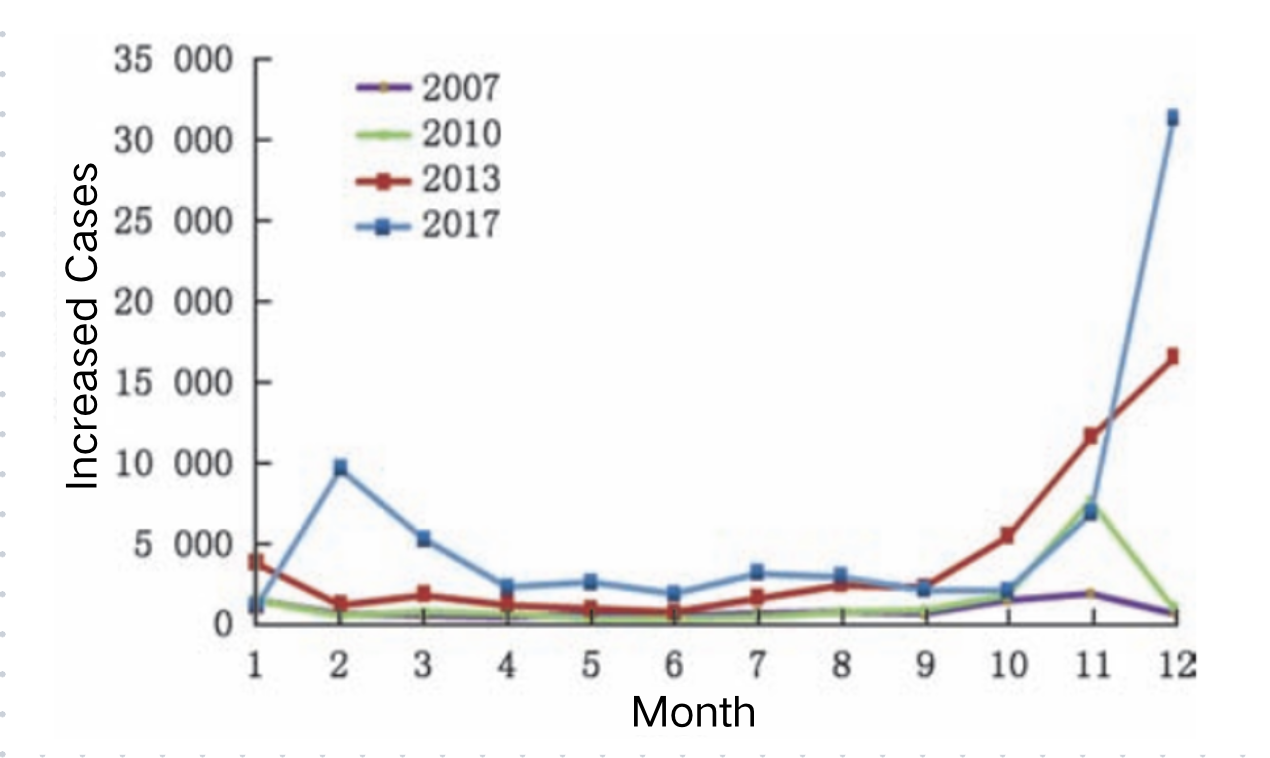

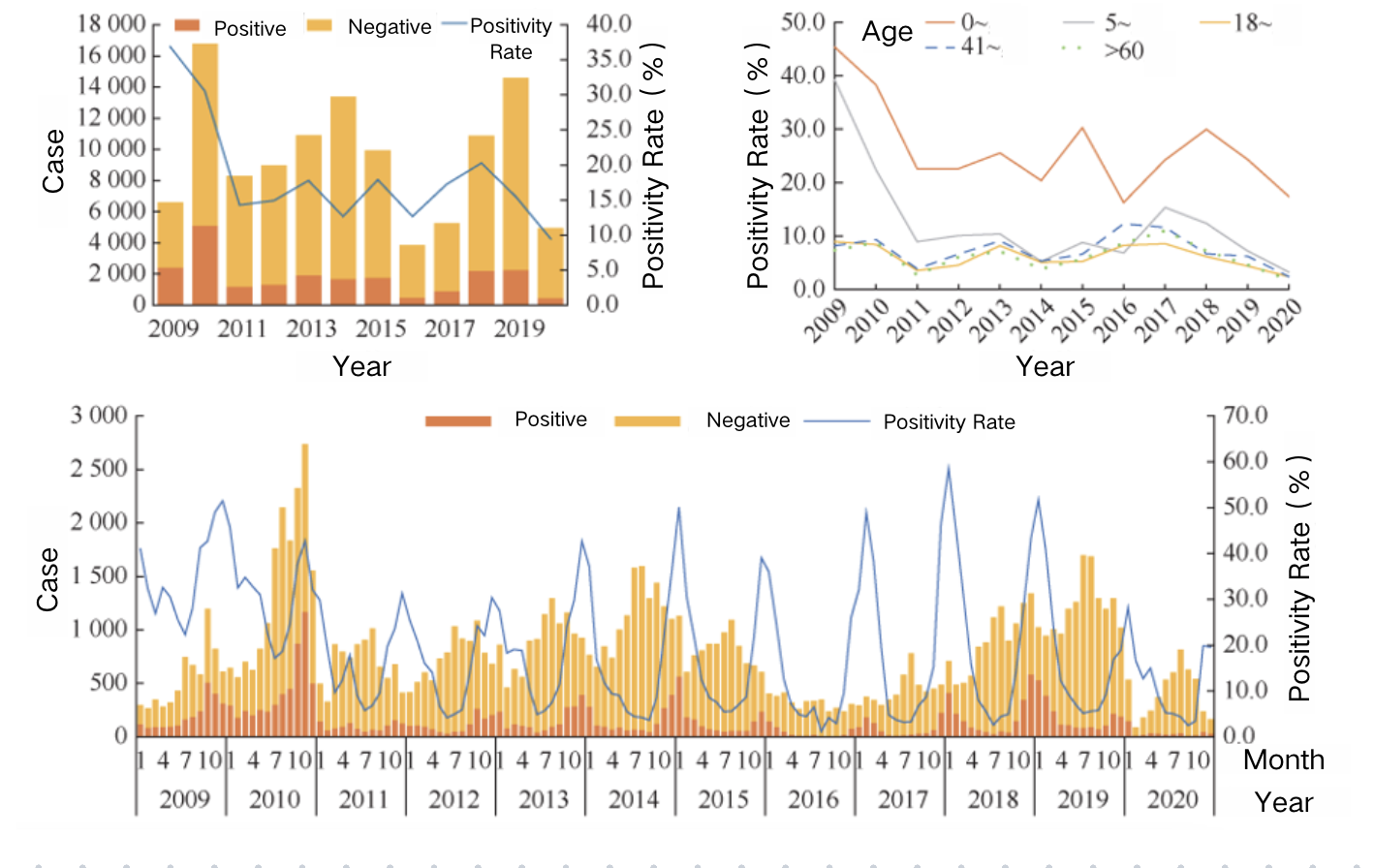

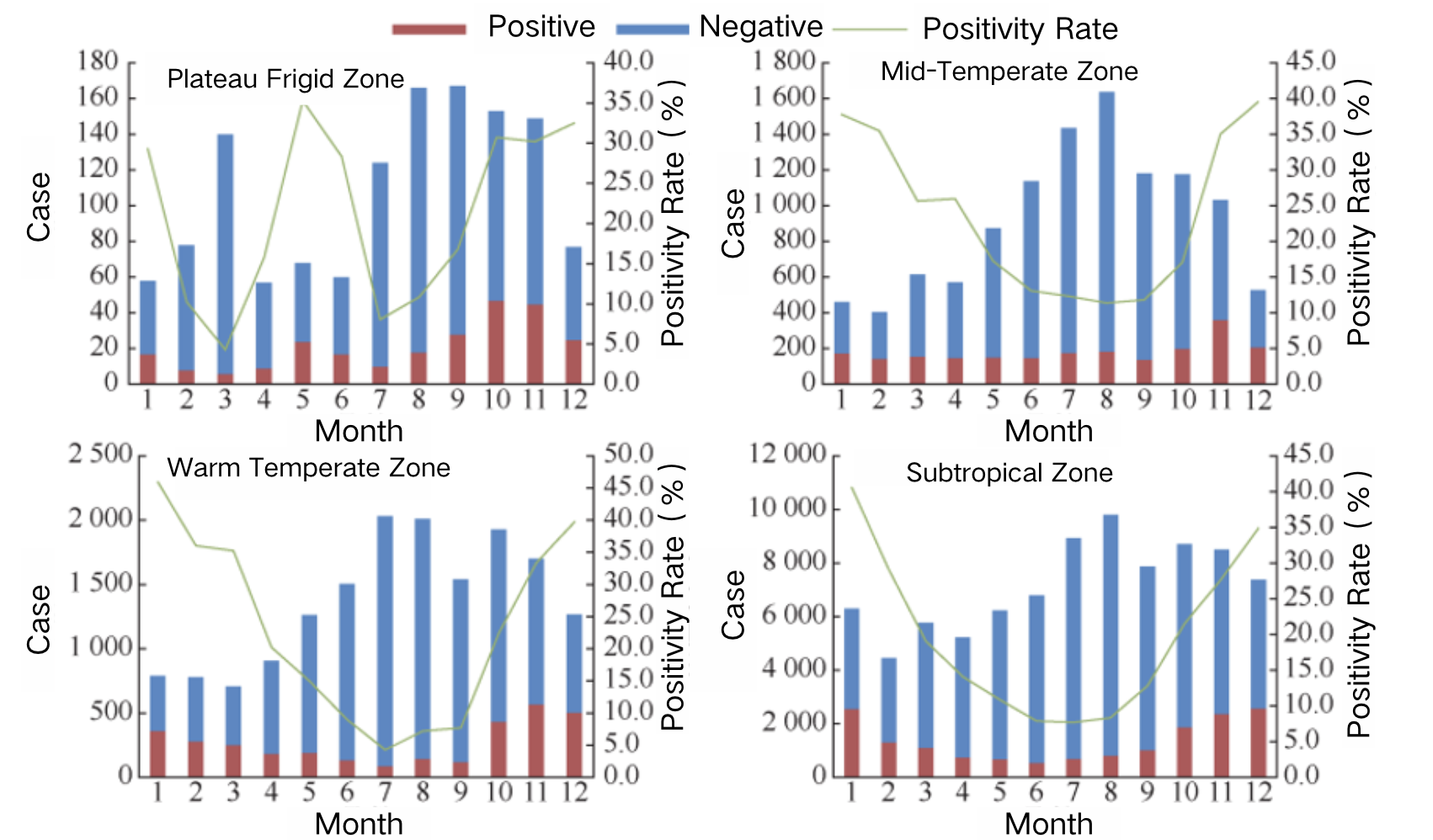

Rotavirus is more easily transmitted during cold seasons, and in recent years, a secondary peak has also been observed in spring in China. It remains the leading cause of diarrhea in children under five years old. RVGE can occur year-round in this population, with a distinct seasonal distribution.³ The peak incidence typically occurs between November and February, often referred to as the “autumn diarrhea” season.

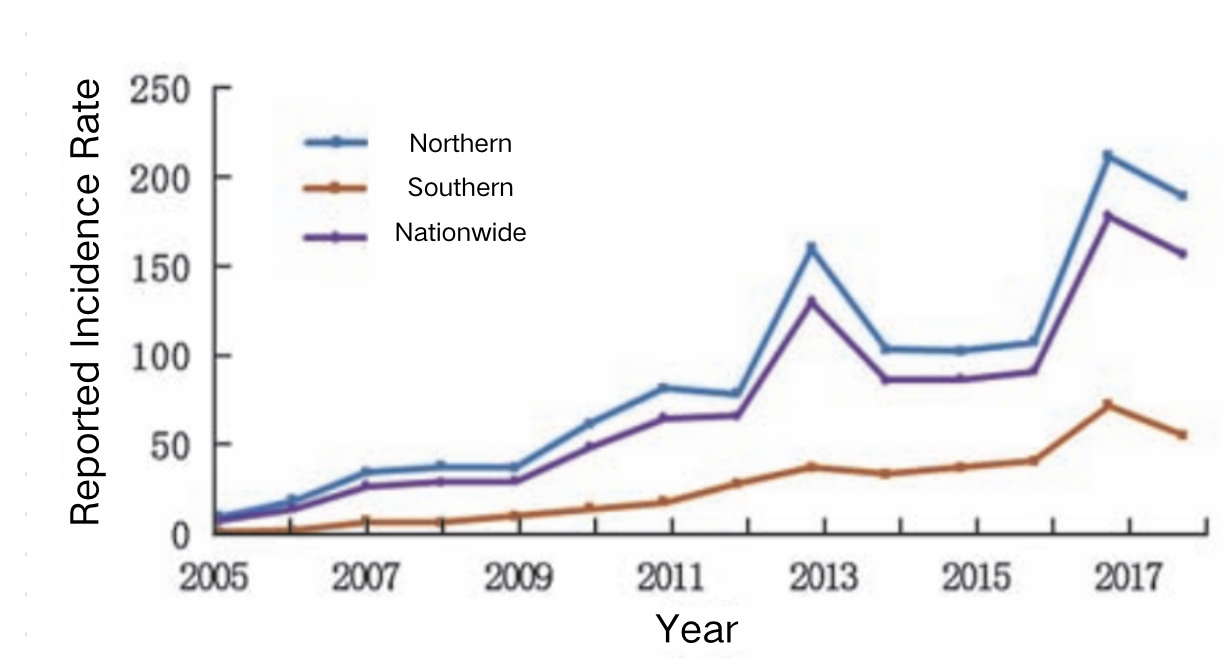

The reported incidence of rotavirus in both southern and northern China has shown a fluctuating upward trend. The reported incidence rate in the south (90.1 per 100,000) is higher than the national average, while the north (26.0 per 100,000) is below the national level. The number of reported cases in the south (745,526 cases) is 9.9 times higher than in the north (74,935 cases). The incidence trend in the south closely mirrored the national pattern, with three peaks recorded in 2013 (160.5 per 100,000), 2017 (211.7 per 100,000), and 2018 (189.7 per 100,000). In contrast, the north only experienced a single peak in 2017 (72.9 per 100,000).¹⁴

Meta-analysis results indicate that between 2011 and 2018, RVGE cases accounted for 34.0% of all diarrhea-related medical visits among children under the age of five in China, with significant regional variations in rotavirus detection rates.²¹ Sentinel surveillance data show notable differences between southern and northern provinces regarding rotavirus positivity rates among hospitalized children with acute gastroenteritis (AGE). From 2016 to 2019, the rotavirus positivity rate in peak months (December or January) was generally higher in southern provinces than in northern provinces. However, from 2020 to 2021, the positivity rate in northern provinces exceeded that of the south.¹⁴ Additionally, the positivity rate during low-incidence months was consistently lower in southern provinces than in northern provinces.

In rural areas of China, the detection rate of rotavirus in RVGE cases is generally higher than in urban areas.²² ²³ A systematic review found that the median detection rate of rotavirus among hospitalized children under five years old was 46.7% in rural areas and 39.8% in urban areas.

Source: Luo Hongmei, Ran Lu, Meng Ling, Lian Yiyao & Wang Liping. Analysis of the Epidemiological Characteristics of Reported Cases of Rotavirus Diarrhea in Children Under Five in China (2005–2018). Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine 181-182-183-184-185–186 (2020).

Source: Luo Hongmei, Ran Lu, Meng Ling, Lian Yiyao & Wang Liping. Analysis of the Epidemiological Characteristics of Reported Cases of Rotavirus Diarrhea in Children Under Five in China (2005–2018). Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine 181-182-183-184-185–186 (2020).

Population Distribution of Rotavirus Infection

Rotavirus infection can occur in all age groups globally, but it predominantly affects children under the age of five. There is no significant difference in incidence rates between males and females. International studies show that approximately 50% of adults develop an immune response after being in contact with children hospitalized for RVGE. In areas where the rotavirus vaccine has been included in the National Immunization Program (NIP), the incidence of AGE and RVGE in older children, adults, and the elderly has decreased. In immunocompromised individuals, such as those with congenital immune deficiencies, or patients who have undergone bone marrow or organ transplants, rotavirus infection can lead to severe and persistent RVGE, potentially threatening life. Surveillance data from Germany, Finland, and Australia show that the proportion of rotavirus infections among the elderly is on the rise. In China, there is a significant difference in rotavirus positivity rates across different populations, with males (20.2%) showing higher rates than females (17.4%). The highest positivity rate is found in children under five years old (28.4%), which is more than four times higher than in adults. The second highest positivity rate is among adults aged 50-60 years and elderly individuals over 60, at approximately 6.0%–7.0%. In terms of annual trends, from 2009 to 2020, the positivity rate for adults aged 18 years and above fluctuated at a low level (1.8%), while the positivity rates for diarrheal patients in the 17-year-old student group and the 0–4-year-old children’s group followed a similar trend, with greater fluctuations, decreasing from 39.2% to 3.3% and from 45.4% to 15.5%, respectively.

The main age group for RVGE patients in China is children under the age of five, with significant regional and temporal differences in cases within this age group. Between 2009 and 2020, rotavirus testing was conducted on 114,606 diarrheal cases from 252 sentinel hospitals across 28 provinces in China. The results showed that 21,872 cases tested positive for rotavirus, with 84.3% of cases being from children under five years old. The incidence of RVGE decreases as age increases.

Source: Tang Bicheng et al. “Epidemiological Features and Genotype Trends of Rotavirus Diarrhea in China from 2009 to 2020.” Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 45, 506–512 (2024)

Source: Tang Bicheng et al. “Epidemiological Features and Genotype Trends of Rotavirus Diarrhea in China from 2009 to 2020.” Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 45, 506–512 (2024).

Content Editor: Xiaotong Yang, Ziqi Liu

Page Editor: Ziqi Liu

References

- Rotavirus Vaccination | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rotavirus/index.html (2023).

- Rotavirus. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/rotavirus.

- Consensus on the Immunoprevention of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis in Children (2024 Edition). 58, (2024). (In Chinese)

- Matthijnssens, J. et al. Uniformity of Rotavirus Strain Nomenclature Proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (RCWG). Arch Virol 156, 1397–1413 (2011).

- Sadiq, A., Bostan, N., Yinda, K. C., Naseem, S. & Sattar, S. Rotavirus: Genetics, pathogenesis and vaccine advances. Reviews in Medical Virology 28, e2003 (2018).

- Avnika B. Amin, Jordan E. Cates, Zihao Liu, Joanne Wu, Iman Ali, Alexia Rodriguez, Junaid Panjwani, Jacqueline E. Tate, Benjamin A. Lopman, Umesh D. Parashar, Rotavirus Genotypes in the Postvaccine Era: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Global, Regional, and Temporal Trends by Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 229, Issue 5, 15 May 2024, Pages 1460–1469, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiad403.

- Mao, T. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of the viral proteins VP4/VP7 of circulating human rotavirus strains in China from 2016 to 2019 and comparison of their antigenic epitopes with those of vaccine strains. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12, 927490 (2022).

- Sashina, T. A., Morozova, O. V., Epifanova, N. V. & Novikova, N. A. Predominance of new G9P[8] rotaviruses closely related to Turkish strains in Nizhny Novgorod (Russia). Arch Virol 162, 2387–2392 (2017).

- Tian, Y., Shen, L., Li, W., Yan, H., Fu, J., Liu, B., Wang, Y., Jia, L., Li, G., Suo, L., Zhang, D., Gao, Z., & Wang, Q. (2024). Major changes in prevalence and genotypes of rotavirus diarrhea in Beijing, China after RV5 rotavirus vaccine introduction. Journal of Medical Virology, 96(5), e29650. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.29650.

- Dennehy, P. H. Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home: The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 19, S103–S105 (2000).

- Goldwater, P. N., Chrystie, I. L. & Banatvala, J. E. Rotaviruses and the respiratory tract. Br Med J 2, 1551 (1979).

- Butz, A. M., Fosarelli, P., Dick, J., Cusack, T. & Yolken, R. Prevalence of Rotavirus on High-Risk Fomites in Day-Care Facilities. Pediatrics 92, 202–205 (1993).

- 2015—2021 Zhongshan City Rotavirus Diarrhea Epidemic Characteristics Analysis – Ding Jinyan.pdf. (In Chinese)

- Luo Hongmei, Ran Lu, Meng Ling, Lian Yiyao, Wang Liping. Analysis of the Epidemiological Characteristics of Rotavirus Diarrhea in Children Under 5 Years in China from 2005–2018. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine 181-182-183-184-185–186 (2020). DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2020.02.013. (In Chinese)

- Yandle, Z., Coughlan, S., Dean, J., Hare, D. & De Gascun, C. F. Indirect impact of rotavirus vaccination on viral causes of acute gastroenteritis in the elderly. Journal of Clinical Virology 137, 104780 (2021).

- Rosettie, K. L. et al. Indirect Rotavirus Vaccine Effectiveness for the Prevention of Rotavirus Hospitalization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 98, 1197–1201 (2018).

- Troeger, C. et al. Rotavirus Vaccination and the Global Burden of Rotavirus Diarrhea Among Children Younger Than 5 Years. JAMA Pediatr 172, 958 (2018).

- Barsoum, Z. Regional hospitalization and seasonal variations of Pediatric rotavirus gastroenteritis pre- and post-RV vaccination: a prospective and retrospective study. World J Pediatr 18, 404–416 (2022).

- WHO. Rotavirus vaccines: WHO position paper. July 2021. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2021, 96(28):301-320. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WER9628.

- Verberk, J. D. M. et al. Impact analysis of rotavirus vaccination in various geographic regions in Western Europe. Vaccine 39, 6671–6681 (2021).

- Li, J., Wang, H., Li, D., Zhang, Q. & Liu, N. Infection status and circulating strains of rotaviruses in Chinese children younger than 5-years old from 2011 to 2018: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother 17, 1811–1817.

- Chen, C. et al. Prevalence of Enteropathogens in Outpatients with Acute Diarrhea from Urban and Rural Areas, Southeast China, 2010–2014. Am J Trop Med Hyg 101, 310–318 (2019).

- Tian, Y. et al. Group A rotavirus prevalence and genotypes among adult outpatients with diarrhea in Beijing, China, 2011–2018. Journal of Medical Virology 93, 6191–6199 (2021).

- Baker, J. M., Dahl, R. M., Cubilo, J., Parashar, U. D. & Lopman, B. A. Effects of the rotavirus vaccine program across age groups in the United States: analysis of national claims data, 2001–2016. BMC Infect Dis 19, 186 (2019).

- Willame, C. EuroRotaNet: Annual report 2014. https://www.eurorotanet.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/EuroRotaNet_report-2020_20211115_Final_v1.0.pdf.

- Tang, Bicheng et al. The Epidemiological Characteristics and Genotype Changes of Rotavirus Diarrhea in China from 2009 to 2020. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology 45, 506–512 (2024). (In Chinese)

- Ma W, Wei Z, Guo J, et al. Effectiveness of Pentavalent Rotavirus Vaccine in Shanghai, China: A Test-Negative Design Study. J Pediatr. 2023;259:113461. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113461.