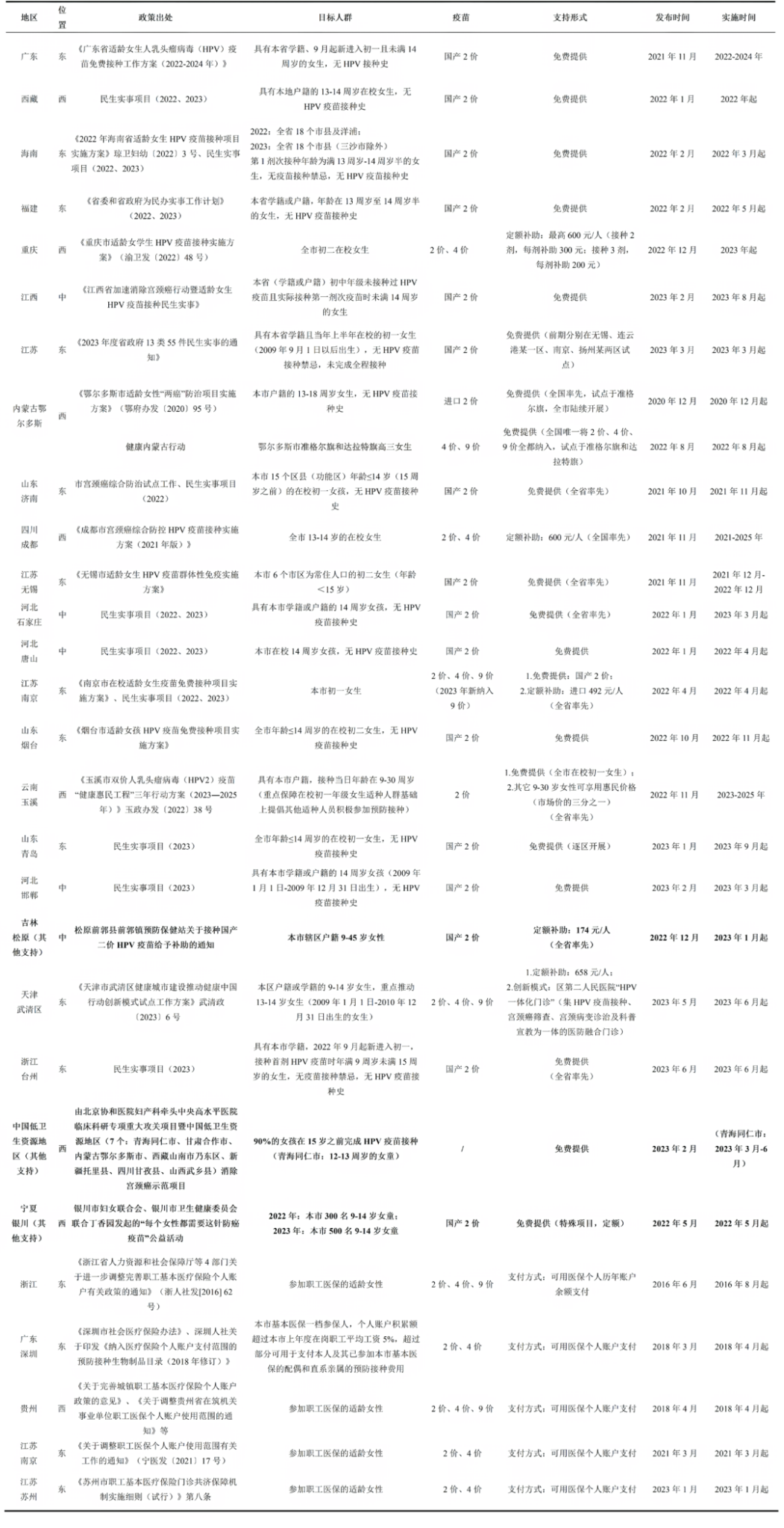

VaxLab Provides Critical Support for Introducing the HPV Vaccine into China’s National Immunization Program

DKU Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research Plays Key Role in Bringing HPV Vaccine into China’s Immunization Schedule

VaxLab Holds Ninth Quarterly Meeting in Nanjing

The Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) convened its ninth quarterly exchange meeting in Nanjing from September 12–13, 2025.

VaxLab Co-Hosted Advanced Infectious Disease Modelling Workshop with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and New York University

Three leading global health universities jointly held an interdisciplinary symposium, Advanced Infectious Disease Modelling Workshop, at Duke Kunshan University from May 26 to 28, 2025, uniting leading researchers and public health experts for in-depth discussions on the latest advancements in the field.

Call for Papers: Vaccines – Special Issue “Vaccination and Public Health Strategy”

This special issue is guest edited by Professor Shenglan Tang, Director of the Vaccine Delivery Research and Innovation Lab (VaxLab); Dr. Lance Rodewald, Senior Advisor for Immunization at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; and Dr. Taufique Joarder, Associate Professor of Global Health Evaluation at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute. We welcome original research articles, systematic reviews, and case studies that examine the challenges associated with introducing new vaccines, and welcome innovative approaches to financing and managing national immunization programs. Papers that discuss national strategies for vaccine procurement, supply chain management, and public–private partnerships that promote the sustainability of immunization are particularly encouraged.

VaxLab Authored WHO Report on Immunization Progress and Challenges in Asia

A recent WHO report authored by VaxLab team highlights the disparities in vaccine coverage and inclusion of vaccines in national immunization programs (NIPs) in 13 Asian study countries. The report launching workshop was held on Feb 10th in Singapore, co-hosted by SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute and the Asia Pacific Immunization Coalition.

VaxLab Held the 8th Quarterly Meeting in Shenzhen

Shenzhen, China – February 14-15, 2025 – The Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) convened its eighth quarterly meeting at the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology (SIAT), Chinese Academy of Sciences, bringing together leading researchers, policymakers, and public health experts to discuss progress and future directions in immunization strategies.

VaxLab and CIKD co-host an international symposium in Beijing

On December 4, 2024, the Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) at Duke Kunshan University and the China International Knowledge on Development Center (CIKD) co-hosted an international symposium in Beijing.

VaxLab’s 7th Quarterly Meeting Convened at Duke Kunshan University

The 7th Quarterly meeting of the Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) was held at Duke Kunshan University on September 12-13, 2024.

VaxLab Held 6th Quarterly Meeting in Peking University

The sixth quarterly communication meeting of the Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) was held on April 1st to 2nd, 2024 at the Peking University School of Medicine.

Is China ready for the HPV vaccine single-dose schedule?

In order to discuss the evidence-based decision-making basis for the immunization program of reduced doses of HPV and PCV vaccines and the related research progress, the Vaccine Delivery Research Innovation Laboratory of Duke Kunshan University organized a technical workshop on May 15, inviting experts and scholars from the World Health Organization (WHO), Johns Hopkins University (JHU), and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences/Peking Union Medical College to share and discuss the topic of “HPV and PCV Vaccine Dose Reduction Discussion: Global and National Experience”.

VaxLab Published a Thematic Series for Advancing the National Immunization Program on BMC Infectious Diseases of Poverty

A thematic series, “Advancing the National Immunization Program in China: Making it More Effective and Sustainable,” was recently published in the BMC Infectious Diseases of Poverty.

VaxLab Held its 6th Quarterly Meeting in Peking University

The sixth quarterly communication meeting of the Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) was held on April 1st to 2nd, 2024 at the Peking University School of Medicine.

Paper

Publications

Closing the immunization gap: Overcoming barriers for new vaccine introduction in Southeast and South Asia

This review, conducted by Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) from Duke Kunshan University, was published in Vaccine. The study systematically compares the status of new vaccine introduction within national immunization programs across 13 countries in Southeast and South Asia, with a particular focus on differences associated with Gavi...

Optimizing immunization through concurrent vaccination: a safety and cost analysis of PCV13 and rotavirus vaccines co-administration in Shanghai

This study, published in Vaccine by Prof. Weibing Wang and team from Fudan University, in collaboration with the Shanghai Municipal Center of Disease Control and Prevention and the Innovation Lab for Vaccine Delivery Research (VaxLab) at Duke Kunshan University, aimed to evaluate the safety and societal economic impact of co-administering

Association between influenza vaccination during pregnancy from 2012 to 2022 and demographic characteristics and preterm birth outcomes in Shanghai

This study, jointly conducted by Prof. Hong Jiang’s team from Fudan University and the Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, was published in the Journal of Clinical Pediatrics. Using data from the Shanghai Birth Medical Information System (2012–2022), the researchers analyzed trends and determinants of influenza vaccination among...